We all know that the Sumali Blue dye holds the key to the identification of a Blue and White of the Yuan and early Ming period. Forgers, past and present, are never able to reproduce the very specific features of the dye. Once we can master the appearances of the dye, there should be little problem in evaluating such B & Ws. The trouble that we have here is that the Sumali Blue dye is quite unlike our present day dye, where you get exactly the same dye if you have the right code number for it. No, the Sumali Blue dye varied and evolved with time during the eight decades when the dye was imported from we-know-not-where to China. Even within the Yuan period, the dye varies quite significantly in its appearance. One good example is the plaques.

Some people believe that plaques are from impurities of the dye. They argue that, as the technology of purification gets better, the many plaques seen in Yuan B & Ws are reduced to almost no plaques in the Xuande era. But if we were to look at the plaques together with the bubbles, another prominent feature of the Sumali Blue dye, we will be convinced that the argument is not valid. The plaques change with time, so do the bubbles. If the plaques are impurities, after their removal, the bubbles should be the same. This is clearly not the case. So, while the statement that the plaques in the B & Ws are getting less from Yuan to early Ming is true, it is for quite a different reason. I believe the exporters, over time, had changed the materials they used in making the dye pigment. Not drastic changes, but similar material that is of a slightly different nature. We have no idea why they should make such changes, but the changes are obvious. This leads to some changes in the ingredients of the dye, and their inherent properties. The changes that we see in plaques over those several decades are testimony to what I have just said.

The changes do not limit themselves to the plaques, other characteristics of the Sumali Blue dye also show some other variations, especially the bubbles. But I have to stress here that the decrease in plaques from Yuan to Xuande does not follow a linear function, rather the pattern fluctuates, so that in some Xuande B & Ws, the plaques can be pretty prominent. But the tendency is such that there is a gradual decrease in plaques from Yuan downwards. The variation in the bubbles is even more difficult to describe. There is not a general statement to fit all situations. That is why, we need to look at many different wares to get an idea of what bubbles would look like in the three different eras. As our experiences in looking at the bubbles grow, we would be more certain of ourselves.

Here, I am going to show you a Yuan Jar, of dragon design, whose Sumali Blue characteristics are quite different from the several Yuan B & Ws that I have shown you (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Figure 1

The jar measures 11 3/4 inches in height, and is 14 3/16 inches in its widest diameter. This is a rather rare jar. While it is common to decorate the neck with huge and rough breaking waves in a Yuan jar, the foot is mostly decorated with petal lappets. Here, both the neck and the foot are of the wave design. The dragon is lively drawn with 4-claw feet. With this uncommon design, we would like to find out if the jar is a real Yuan jar. Let us look at the specific features of the dye, and see if they fall into the category that we have attributed to the Sumali Blue dye.

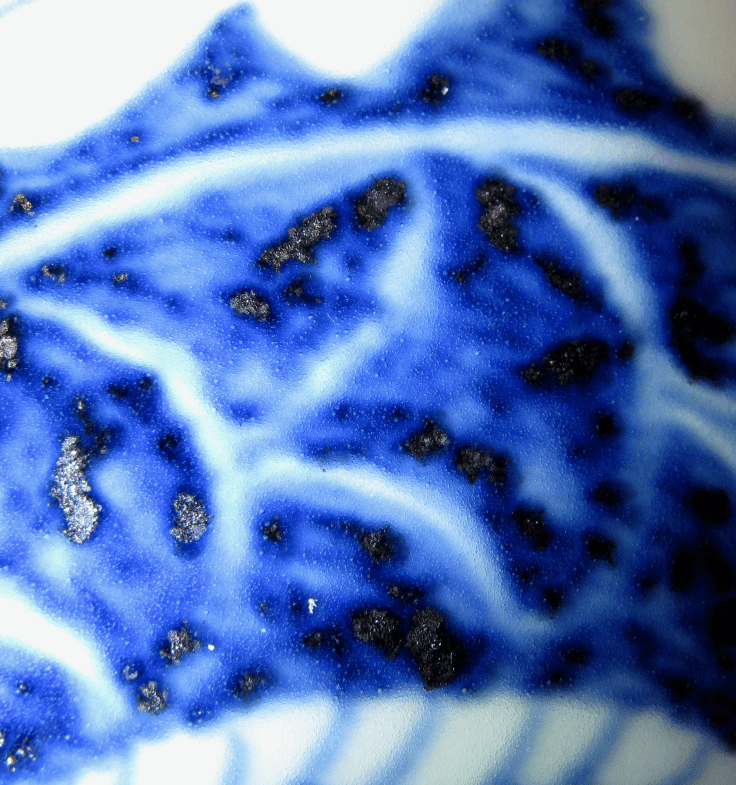

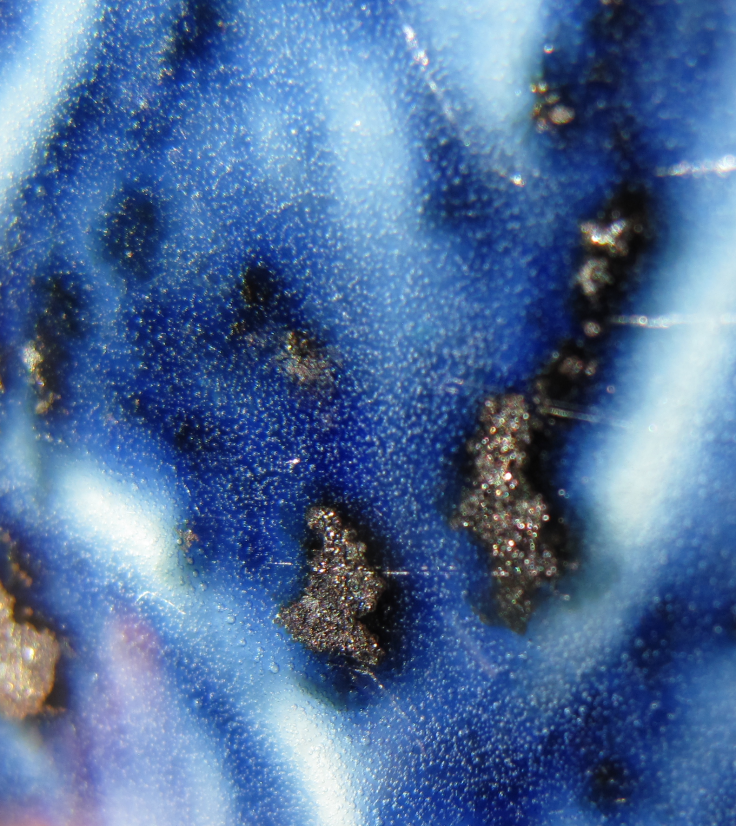

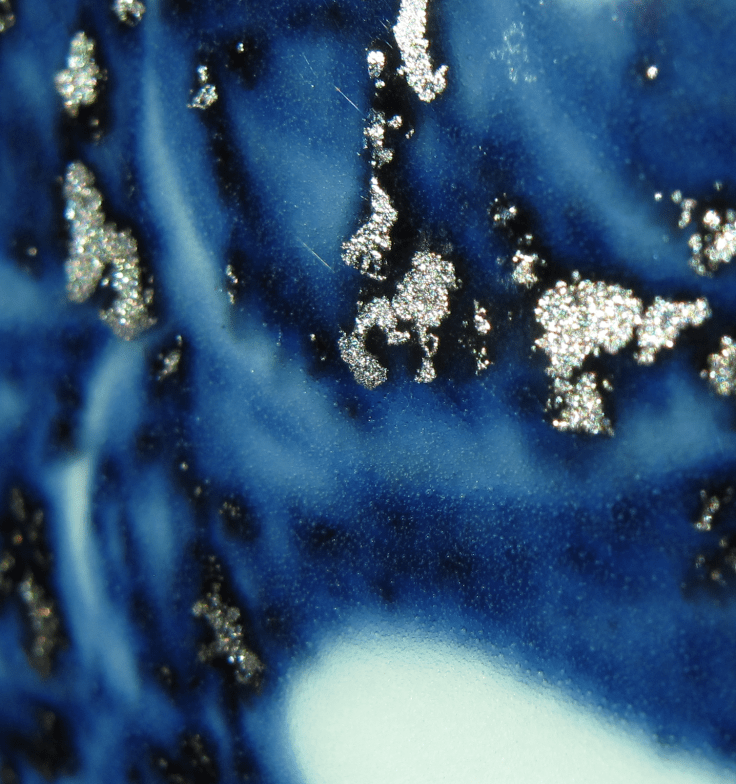

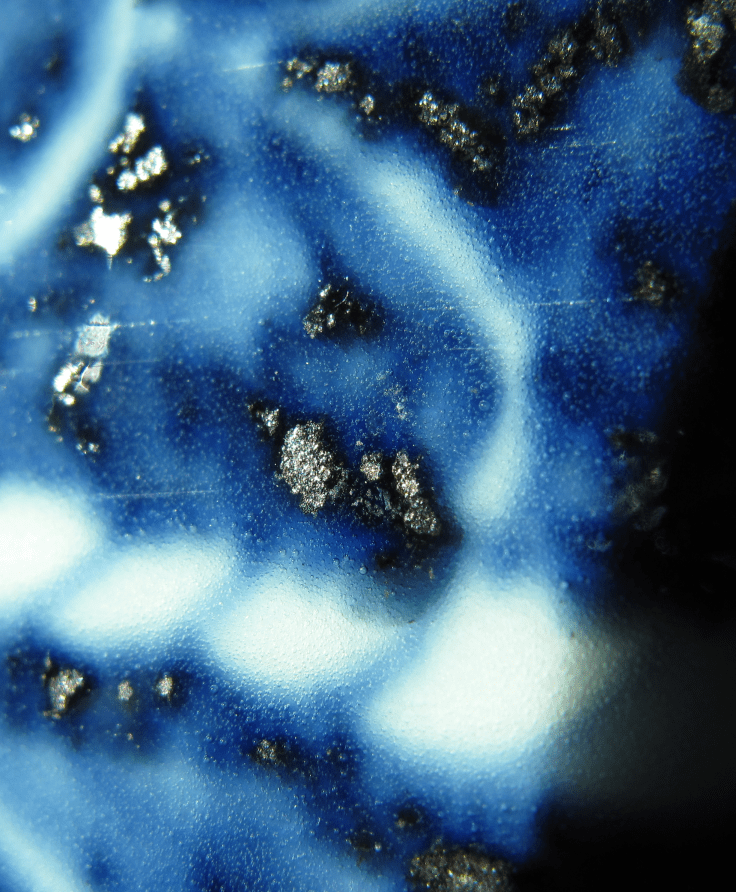

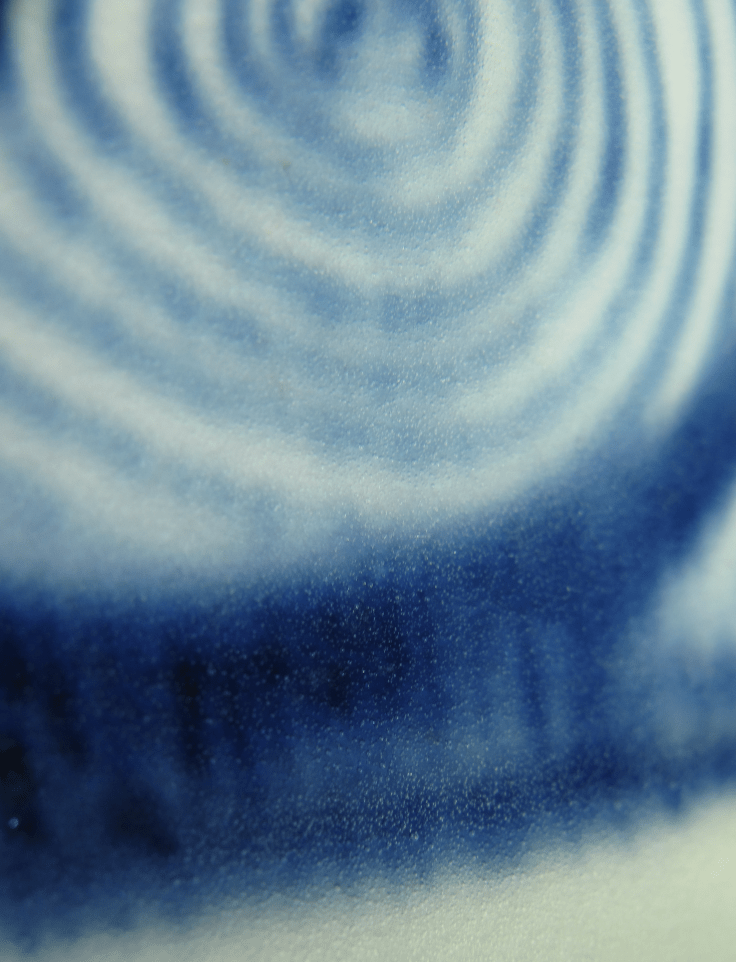

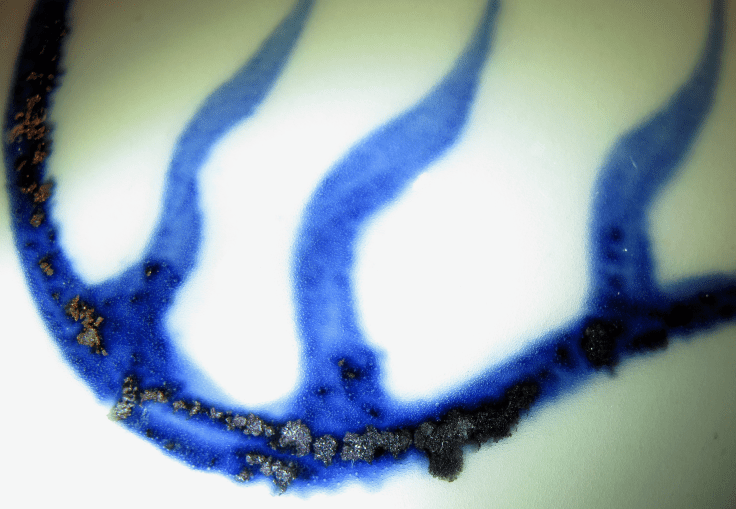

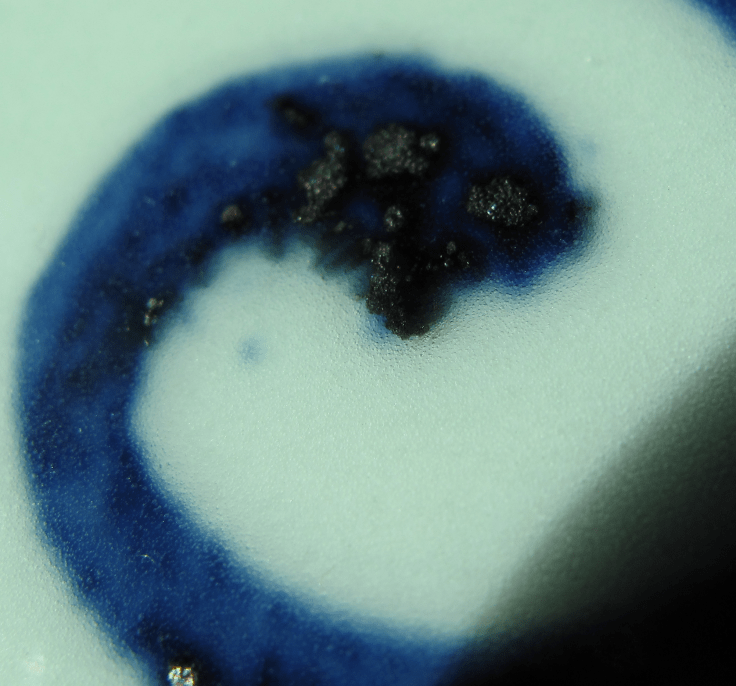

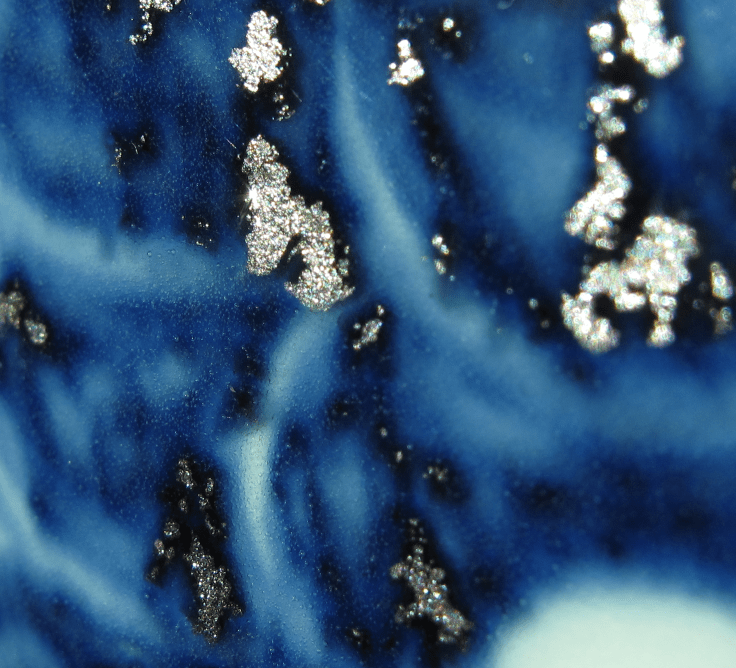

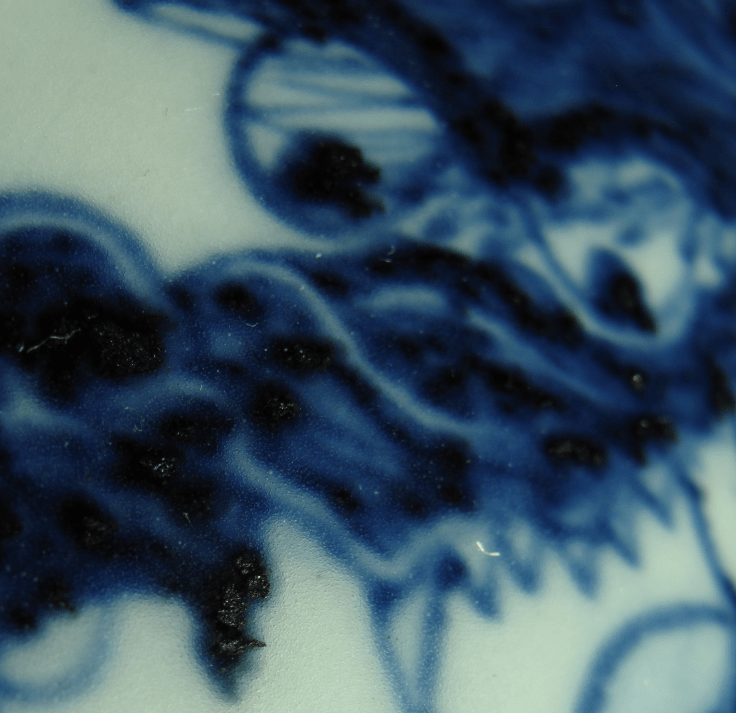

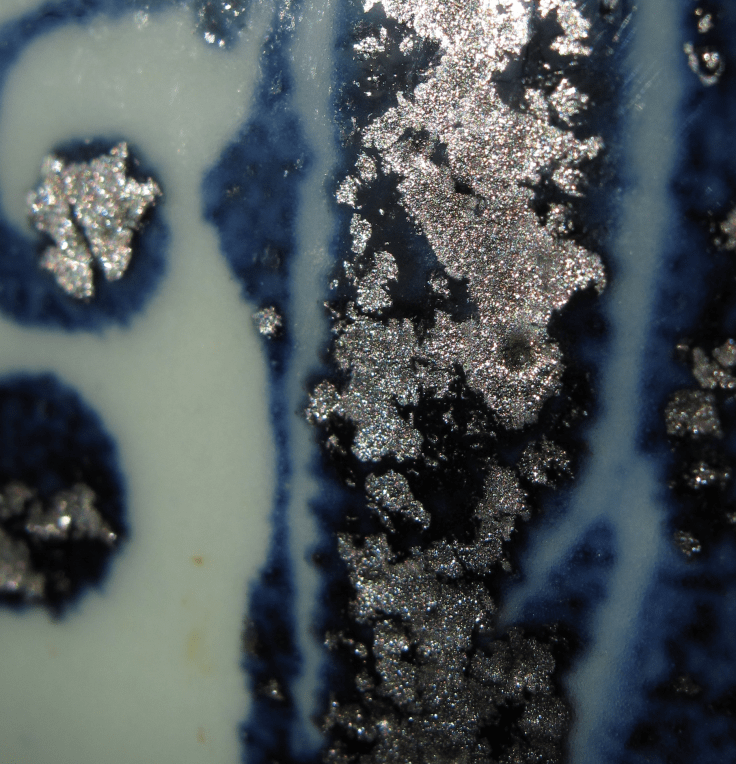

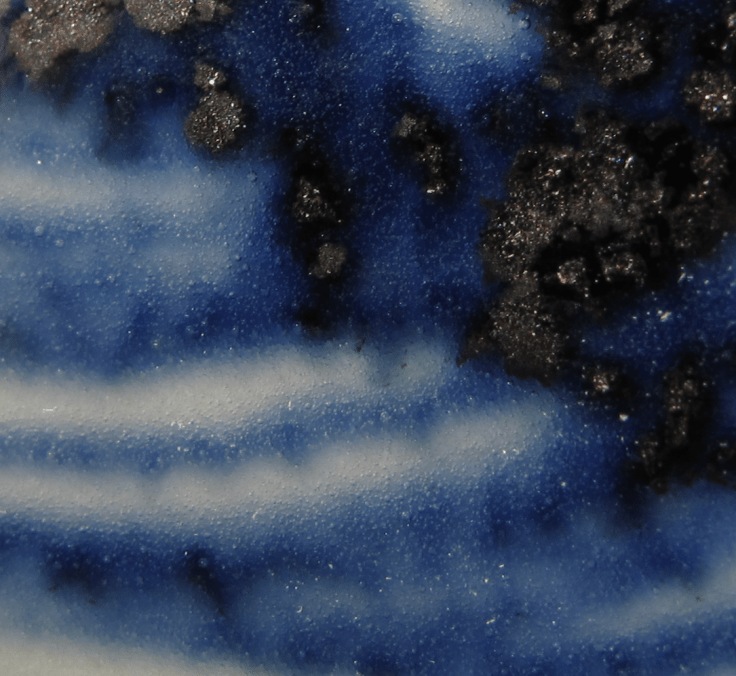

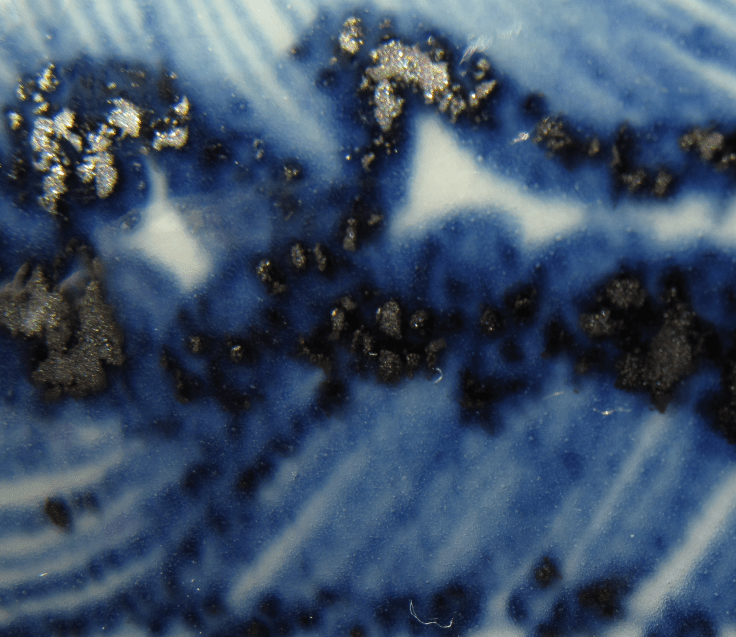

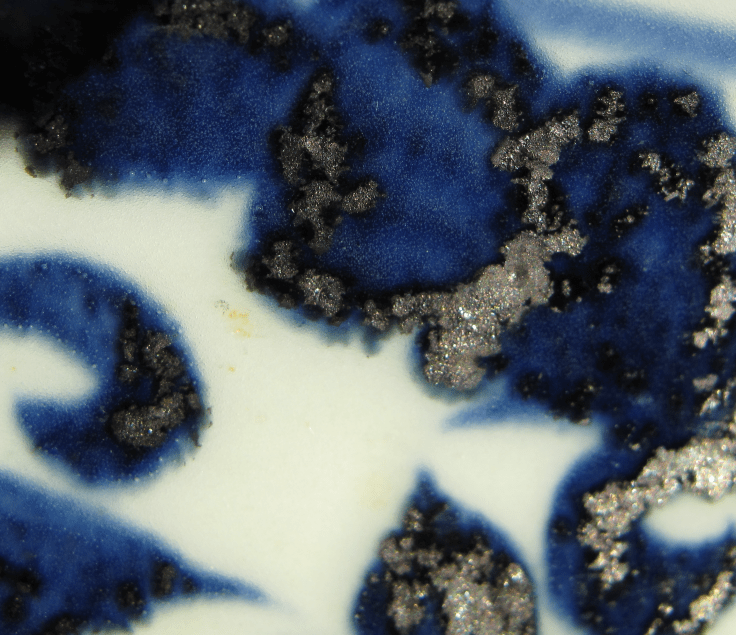

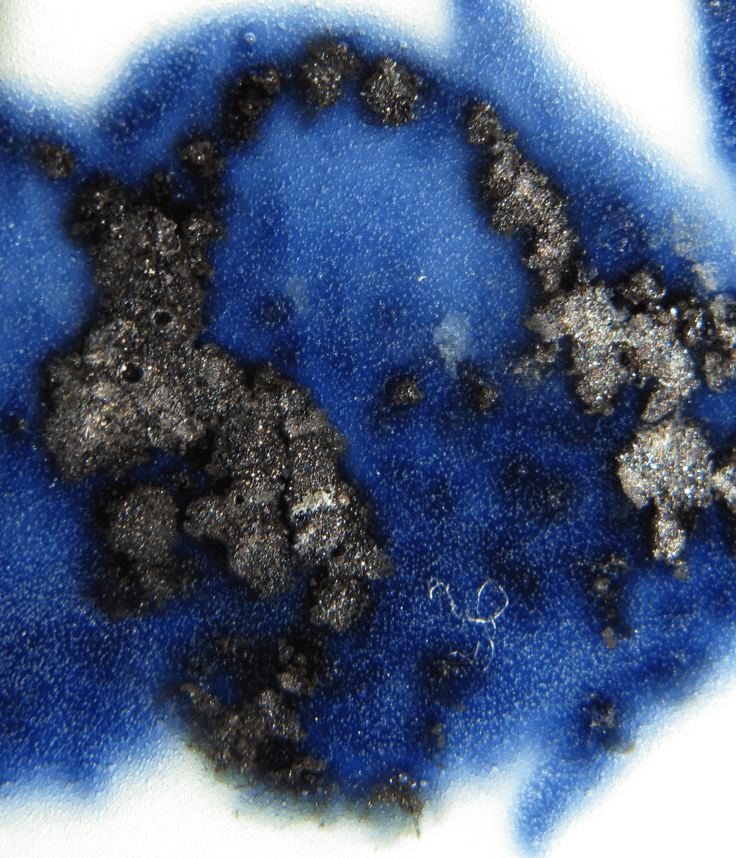

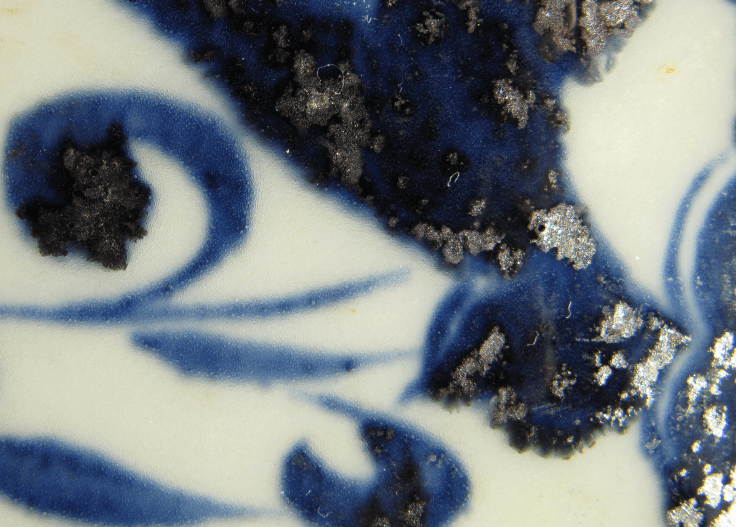

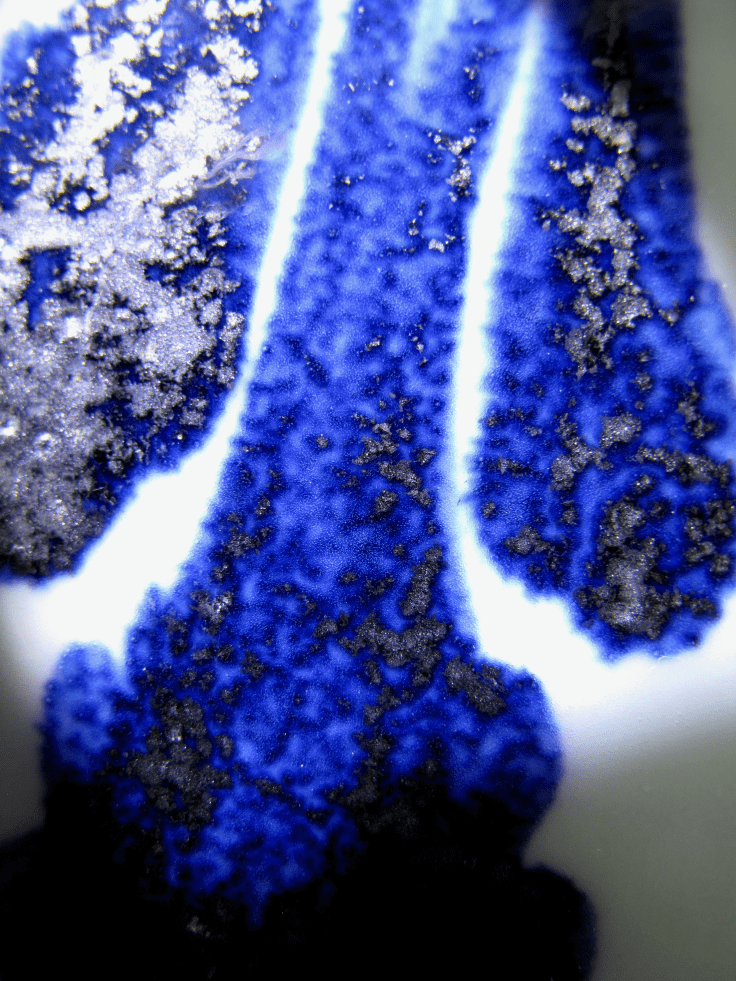

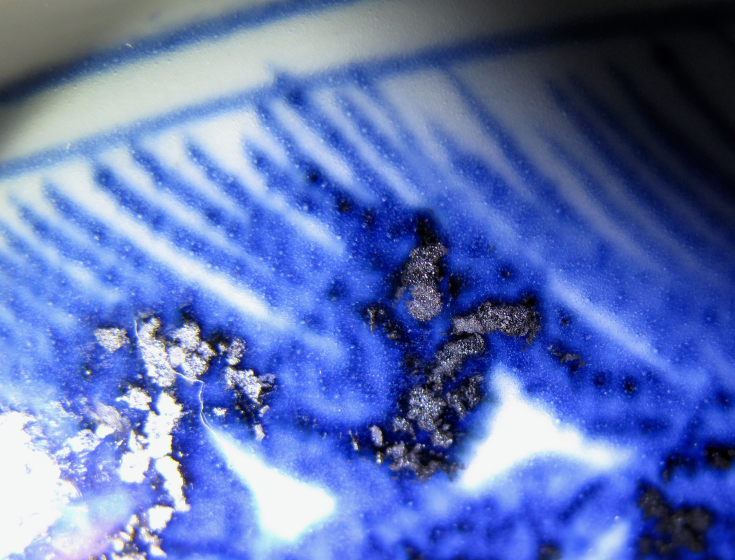

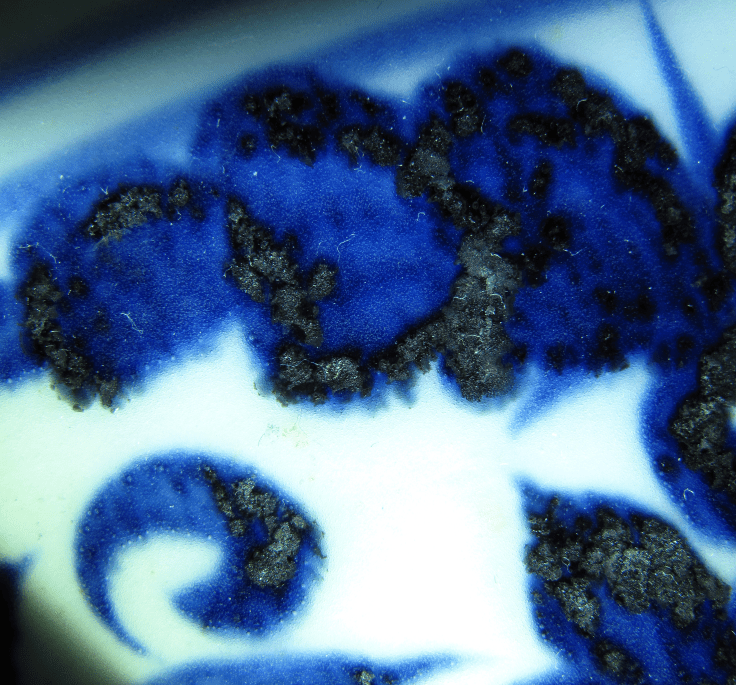

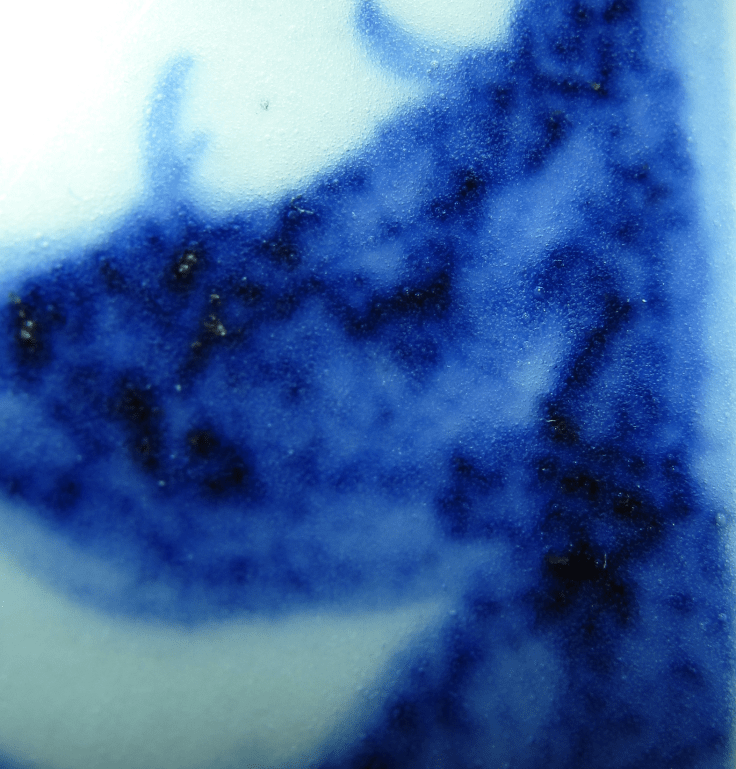

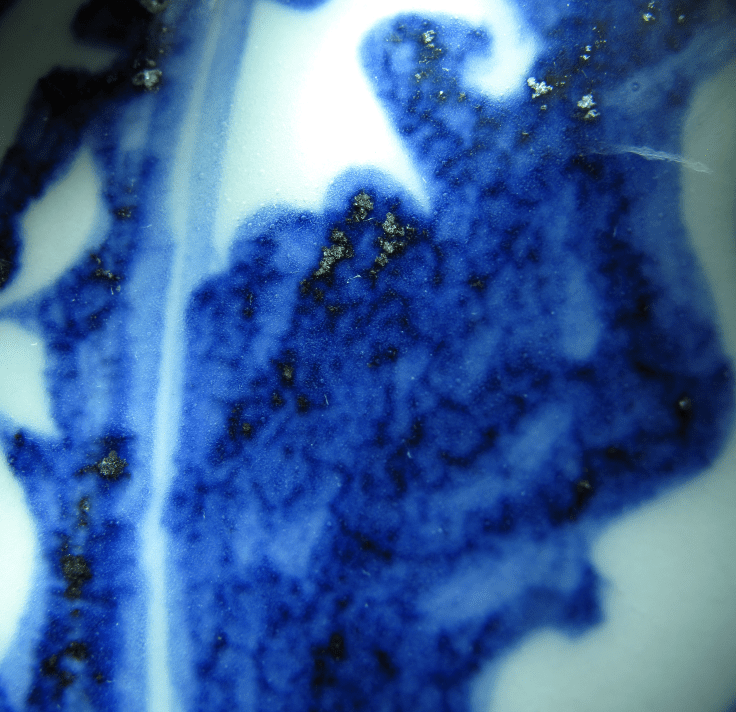

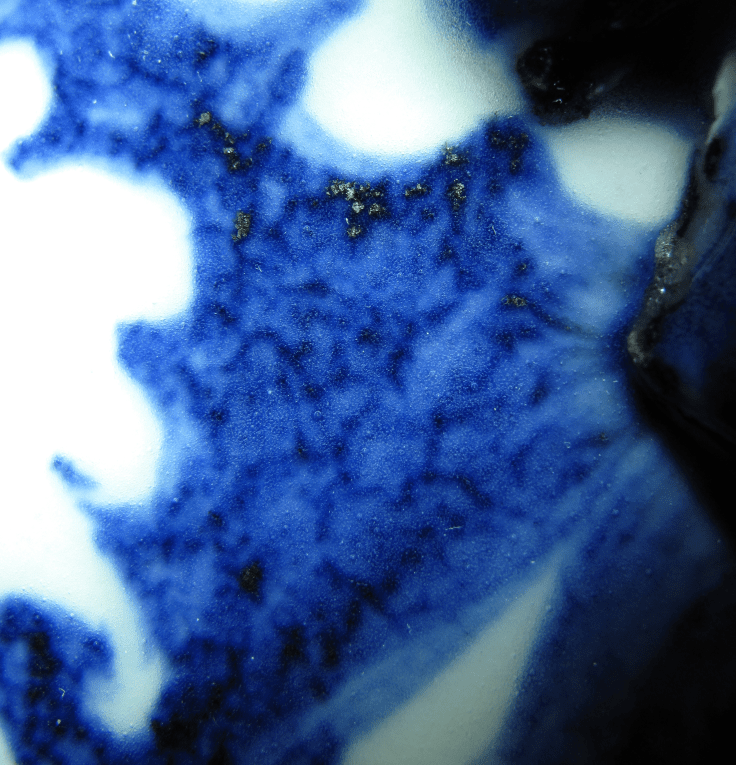

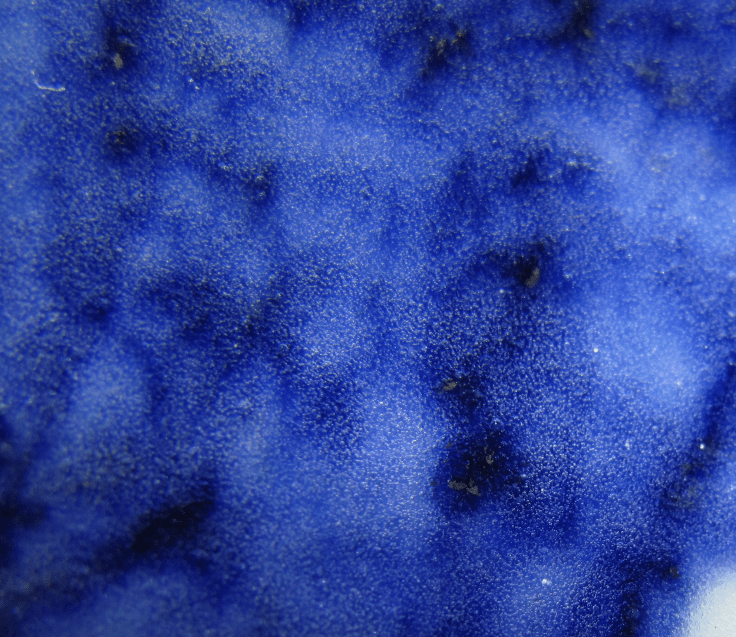

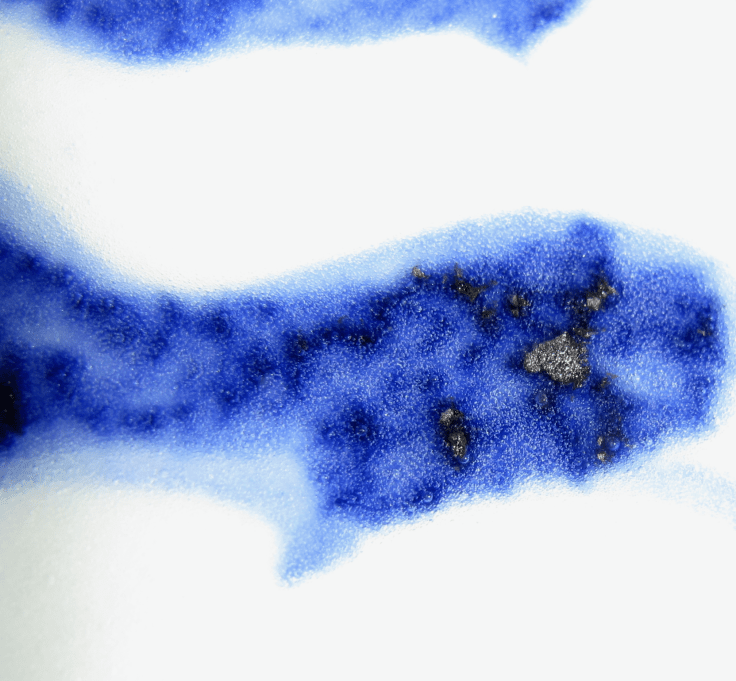

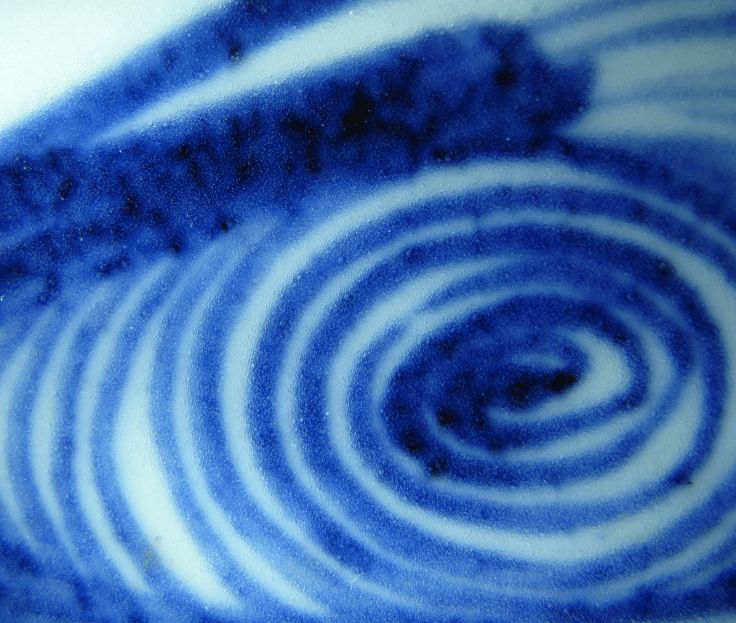

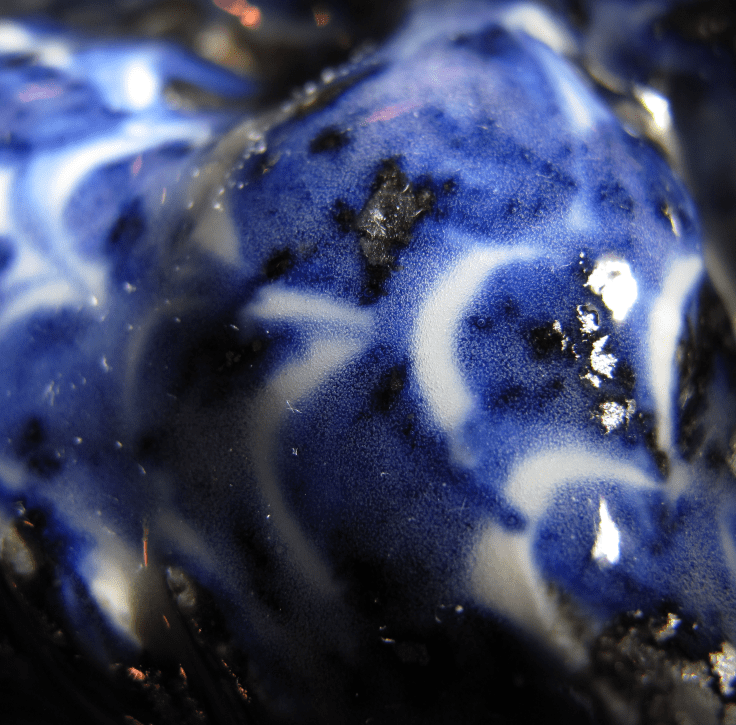

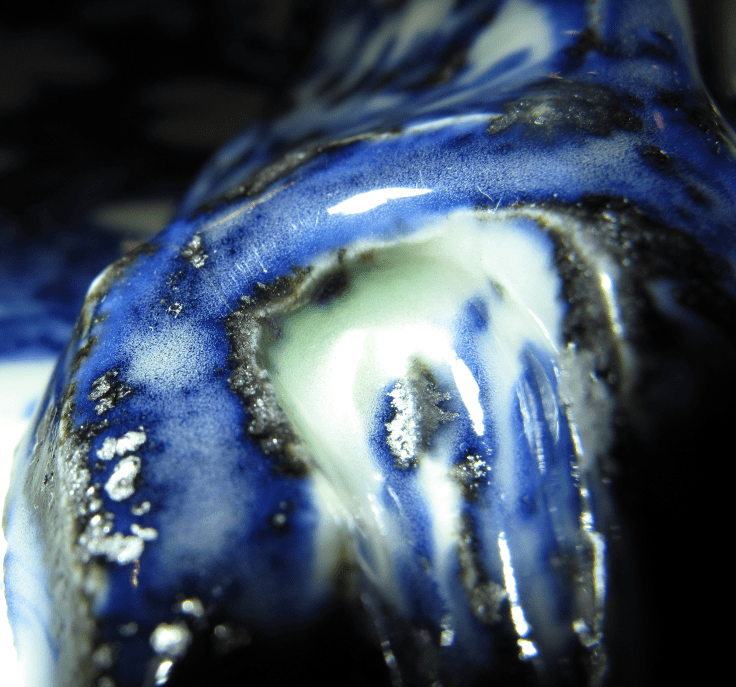

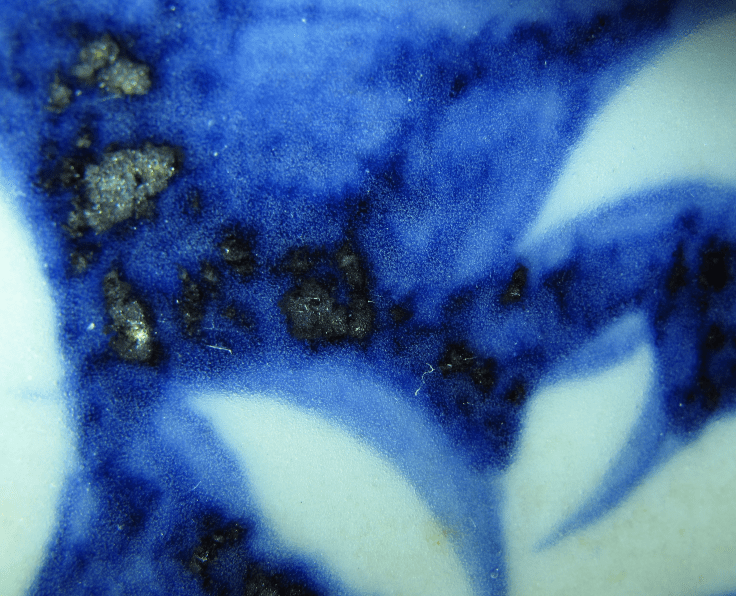

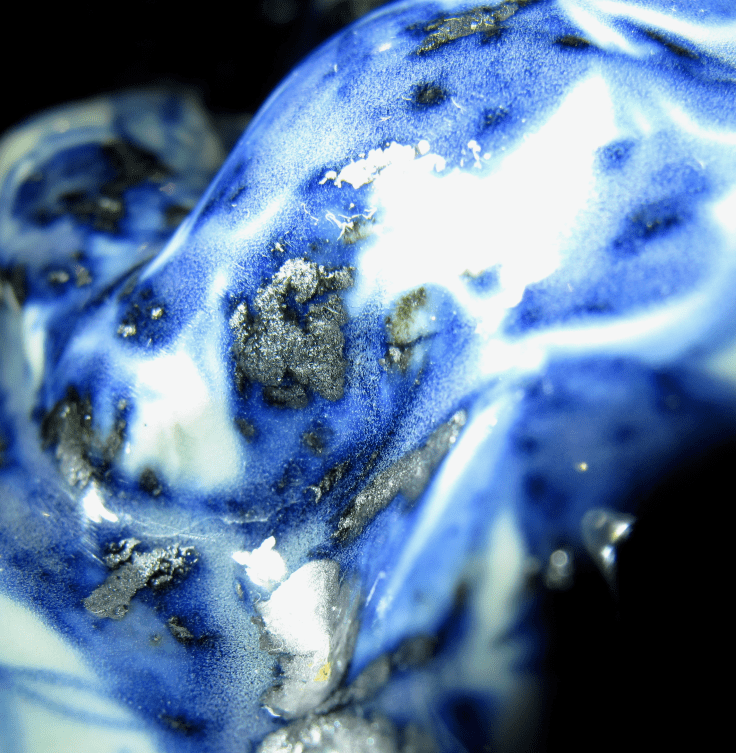

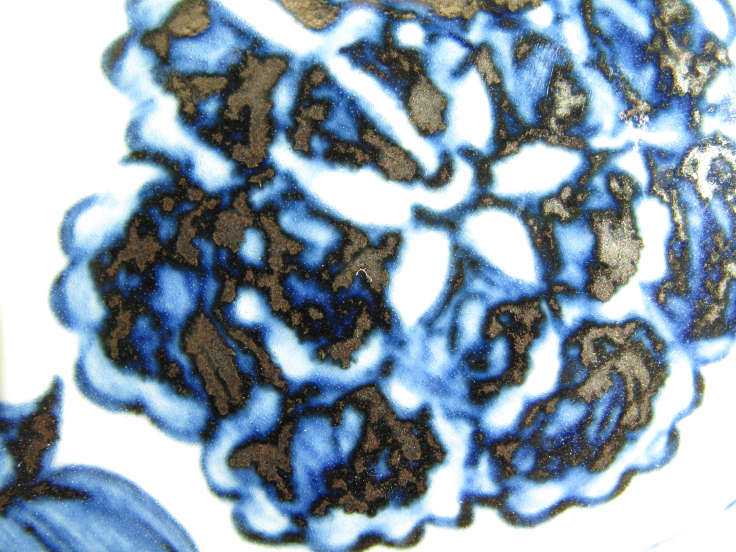

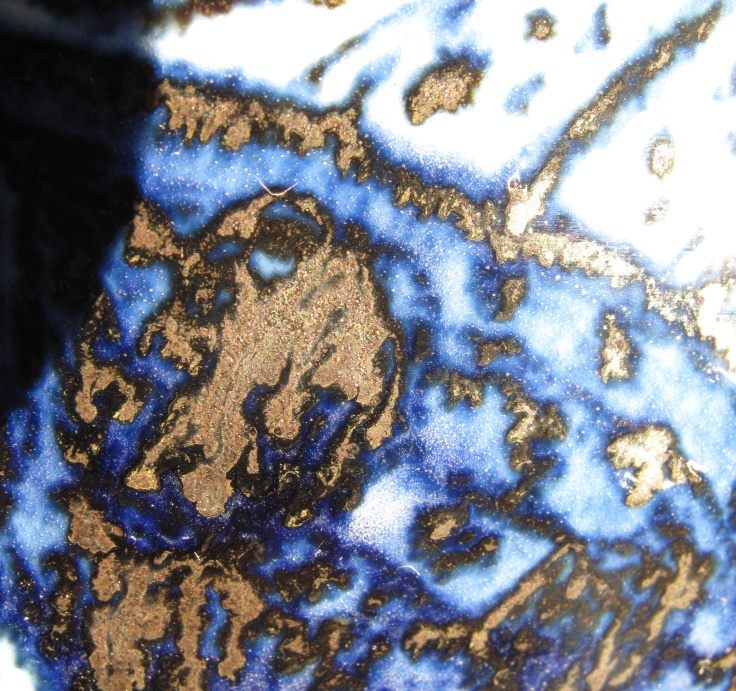

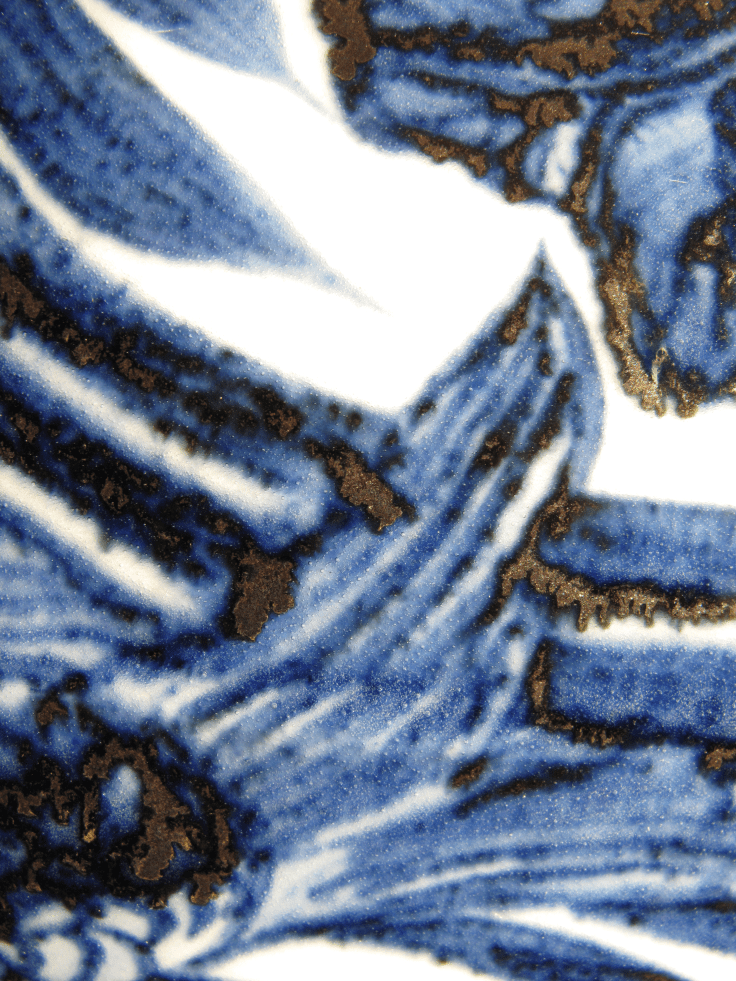

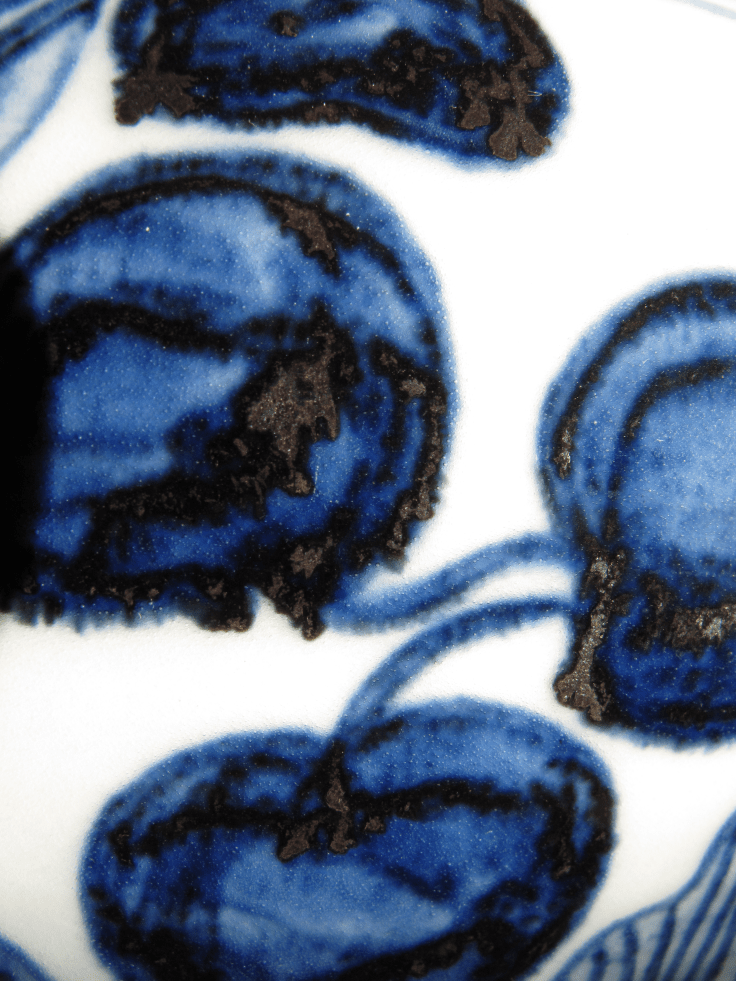

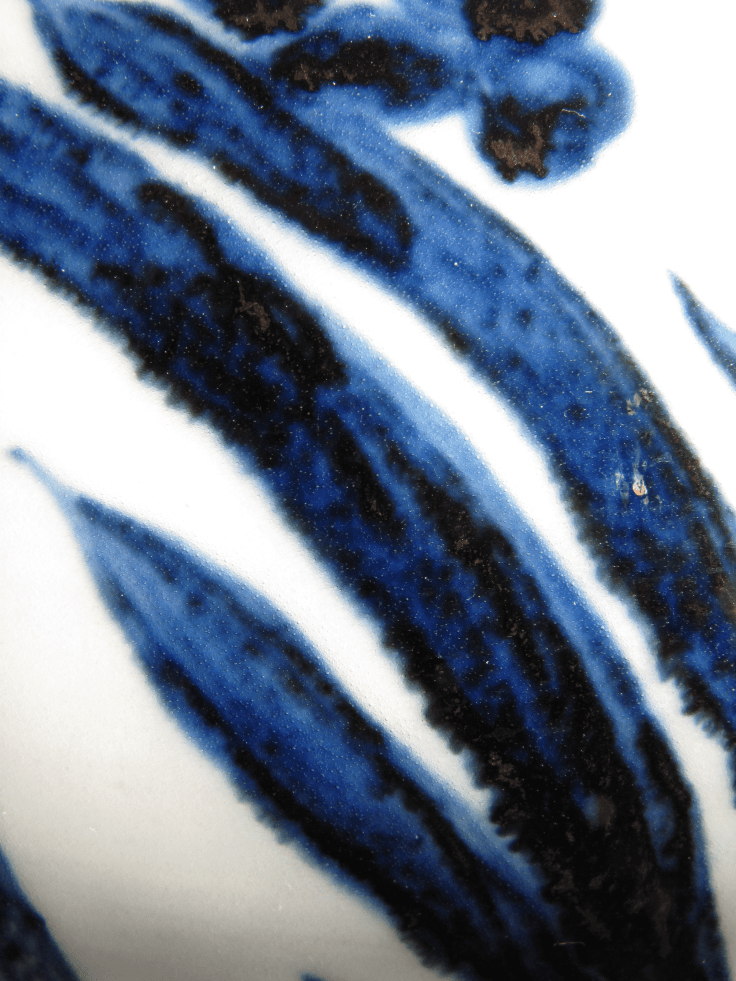

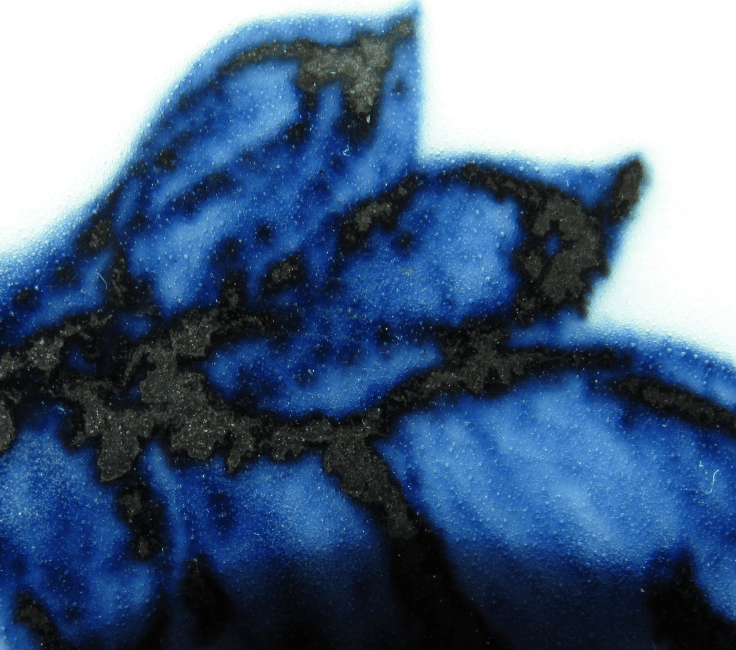

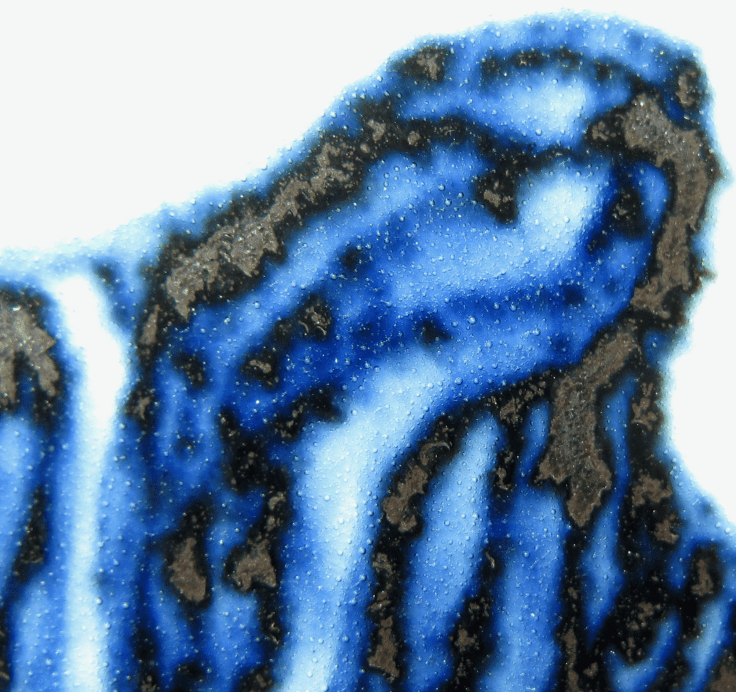

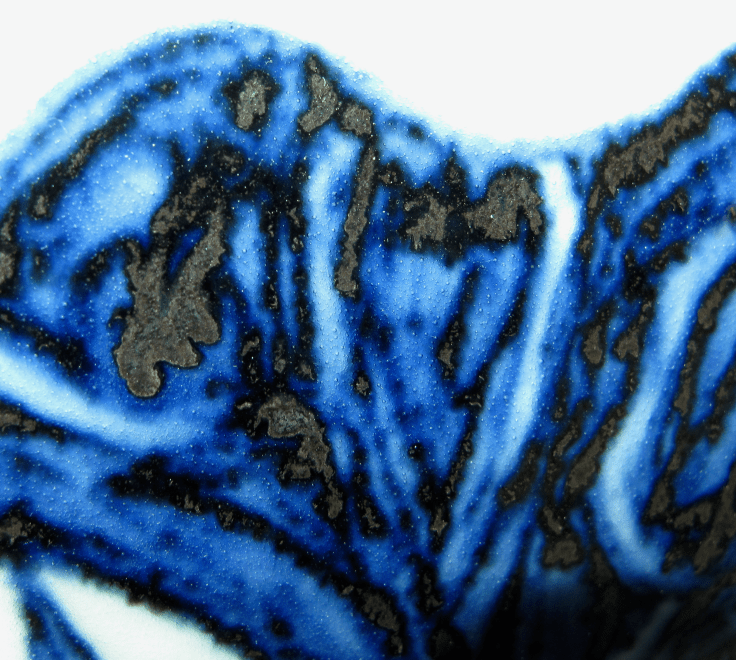

Let me first show you the plaques in this jar (Figure 2-7). You will agree with me that the plaques in this jar is less numerous than the few Yuan B & Ws that I have shown you. But the basic structure is quite the same. The granules are coarse, and under the sun, they have beautiful and colorful reflections that is very much enhanced when the plaques are slightly out of focus (Figures 4-5). But these plaques also have similarities to those found in the Yongle B & Ws. Look at these photos carefully, and you will find that some of the plaques have spiky and sharp edges, a feature that is very prominent in Yongle wares. When I say the exporters were making changes in the ingredients of the dye from time to time, the changes seen here can serve as some form of proof.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 7

Before I leave the plaques, I have to stress again that when you look at these photos, don’t just look at the plaques, pay attention to the bubbles and flares and drippings as well.

You will notice that, in these photos, the drippings and flares are quite easily seen. But I’ll show you more (Figures 8-16).

Figure 8

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 16

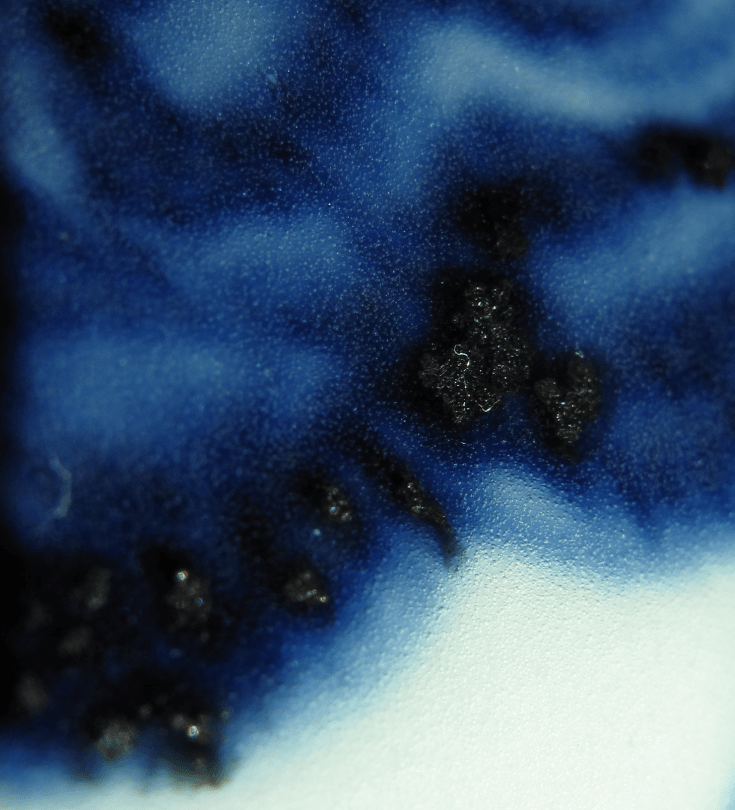

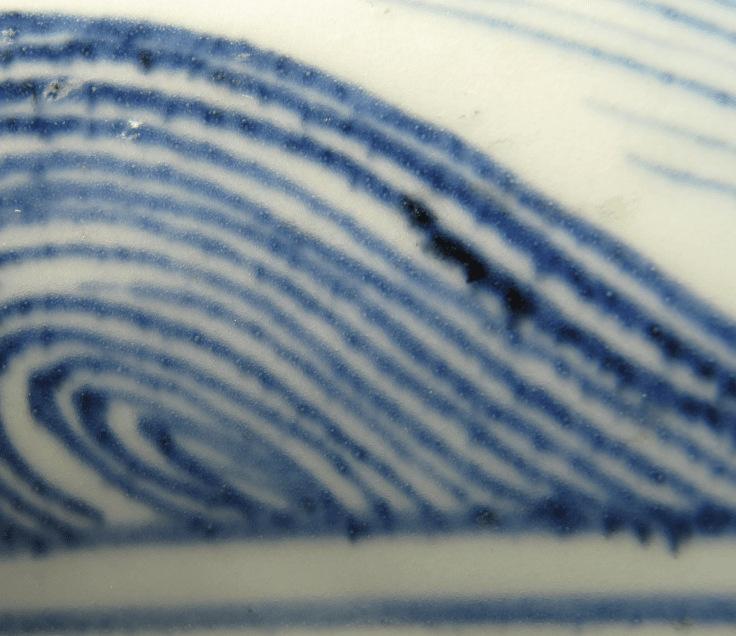

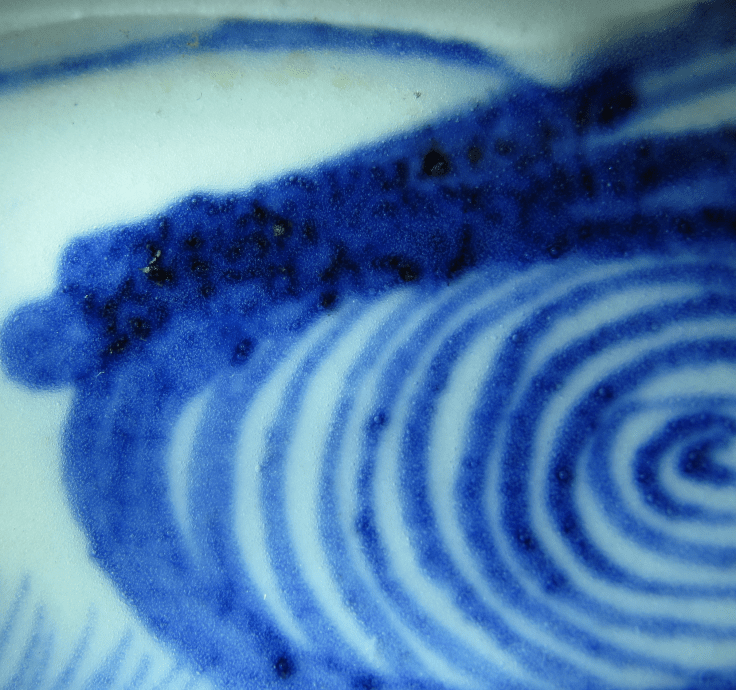

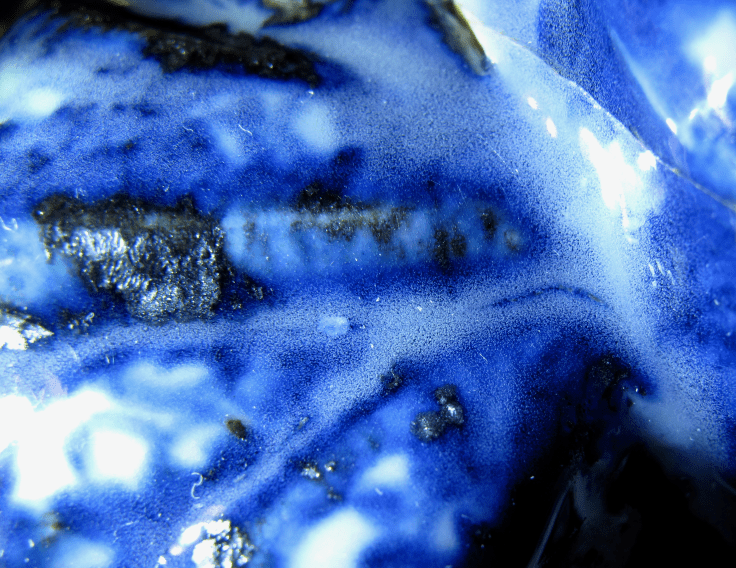

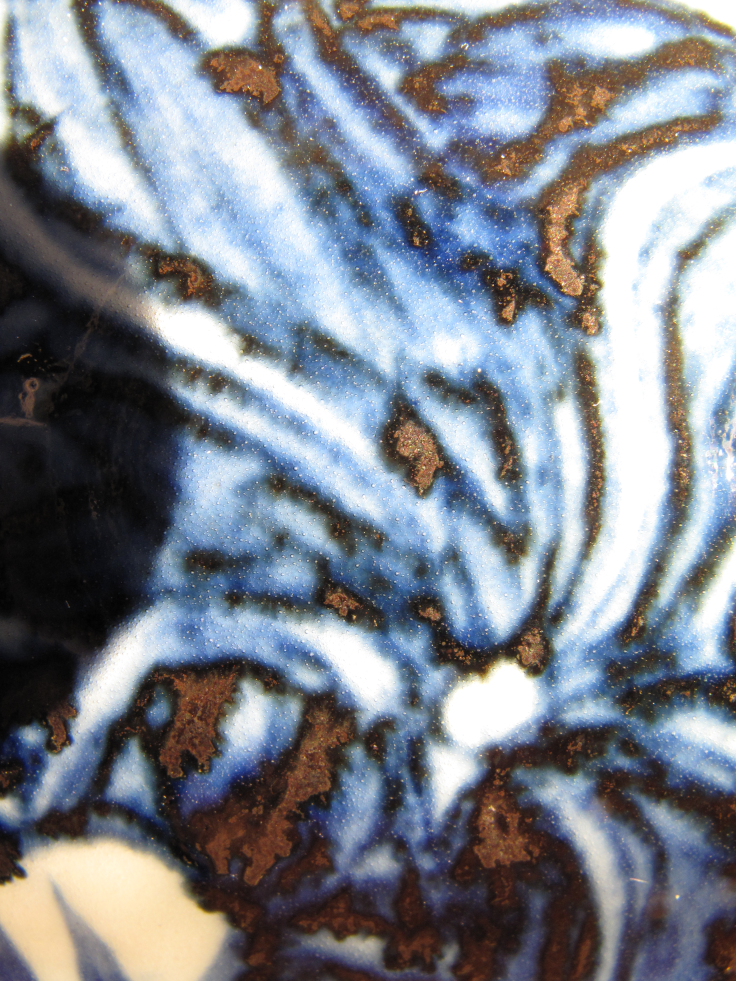

The flares shown in these photos are all exaggerated because of the globular shape of the jar. The motif is drawn, for the most part, on a nearly vertical wall, so that the flare is in fact very much enhanced by the dripping effect, which, as I have explained, is brought on by the gravitational force. In Figure 15 and some other photos, if you care to look at them closely, this gravitational force has its effect also on the thickened plaque, so that the plaque becomes part of the dripping. This is not uncommon in Yuan B & Ws where excessive plaques are of frequent occurrence. The excessive flares/drippings seen in Figure 8 come about for a different reason. If we look closer, the flare/dripping is near where the lower part of the neck meets the global body. The neck is short, but not too short, so that, if the painter applied too much glaze over the neck, there is more glaze to flow down. This will bring with it more blue dye pigment, allowing this exaggerated dripping to occur.

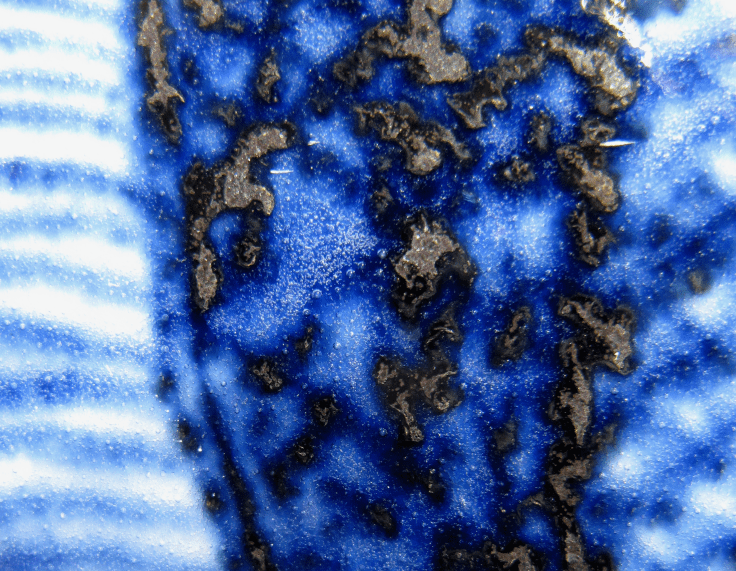

These photos are worth some close study, for they show various presentation of the flare/dripping effect. They show little difference to those flare/dripping in the other Yuan and Yongle B & Ws that I have shown you. It is importance to know their appearances well. These appearances, together with the plaques, would allow you to make a verdict that the ware is a genuine Yuan B & W, even without looking at the bubbles. But bubbles would add further evidence that your verdict is beyond doubt.

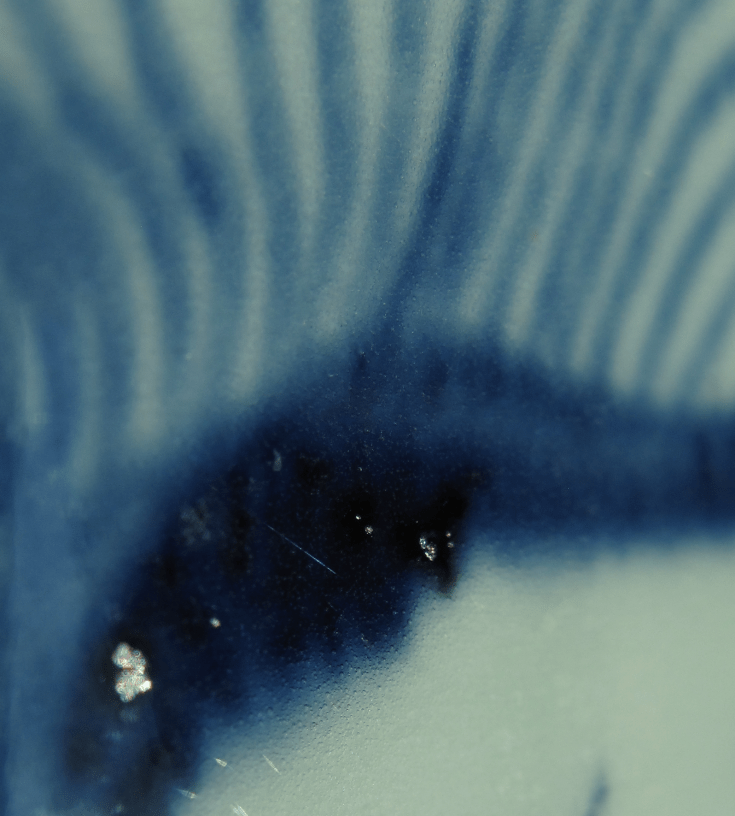

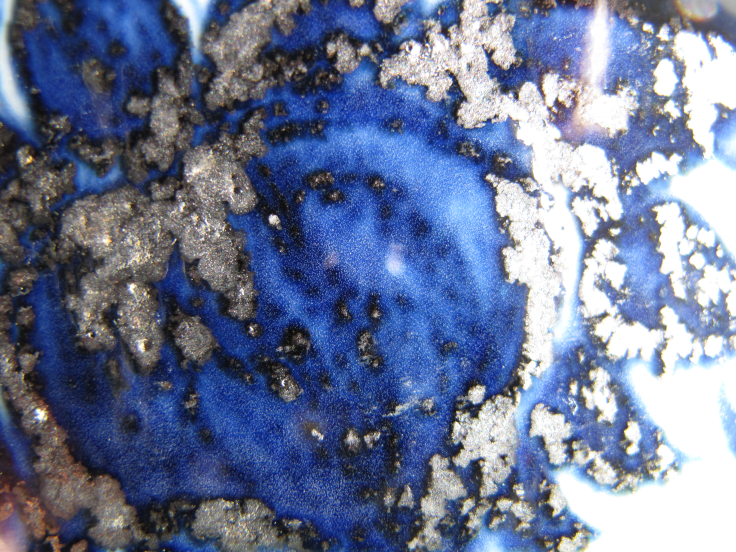

Now, I’ll show you bubbles in this Yuan jar.

Figure 17

Figure 17

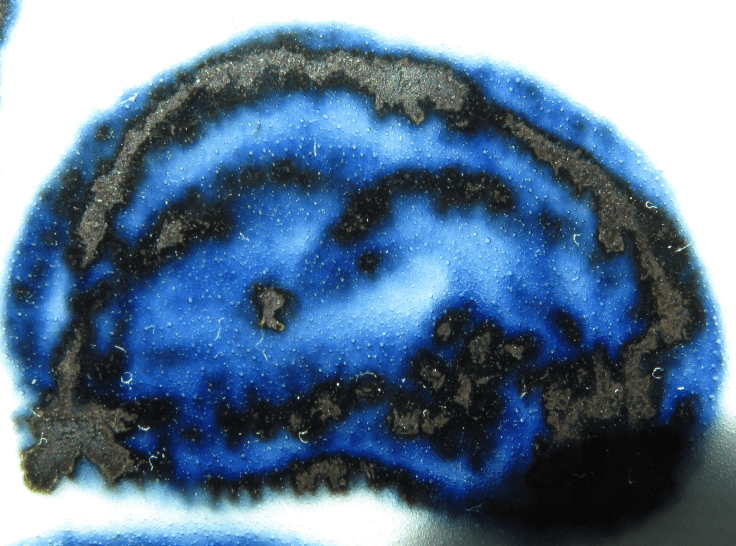

Here in this photo, look at the string of large bubbles in that patch of flare/dripping, and some other large bubbles in adjacent areas. These large bubbles are not really as large as those large bubbles in the Yongle era, but they too have this semi-opaque appearance. You will also note that when I say semi-opaque, it does not mean that they are semi-opaque to the same degree. Some are more semi-opaque than the other, some are less so. But these semi-opacity is a characteristic of the Sumali Blue dye and you need to recognize this feature. The small bubbles are not too closely packed, but they are dense enough to allow you to see the lacuna formation.

Figure 18

Figure 18

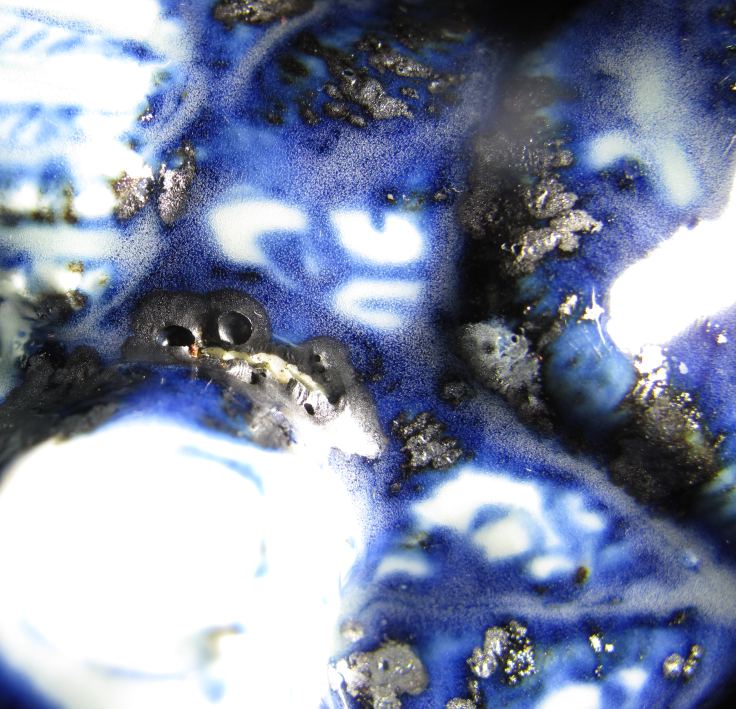

Here in this photo (Figure 18), at a glance, you do not see many large bubbles. But if you enlarge them, and look inside the dark part of the dye, you will see many larger bubbles are hiding inside the dark shadow. This, again, is a feature of the Sumali Blue dye.

Figure 19

Figure 19

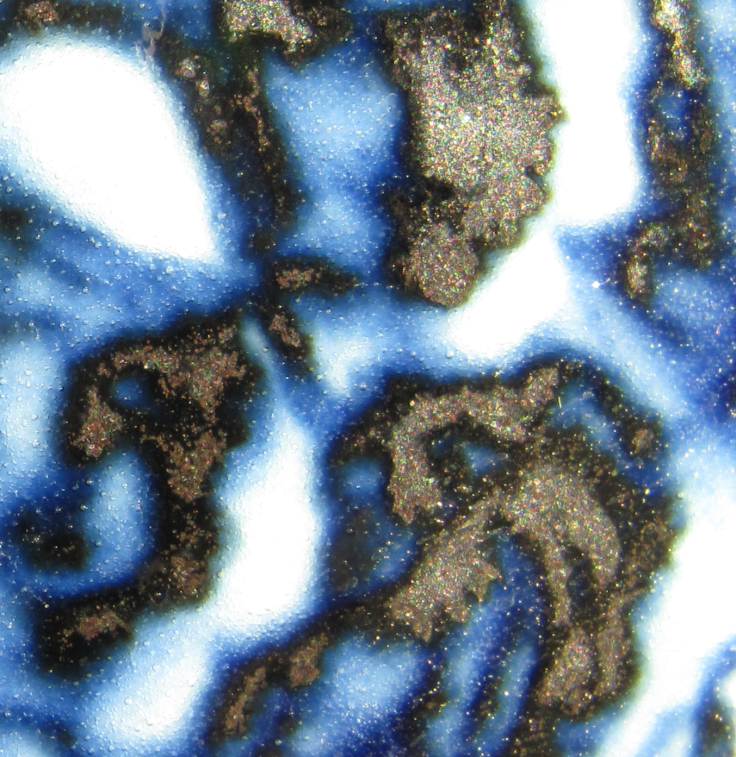

Figure 19 is a nice photo. Look at the very nice bubbles, large and small. The distribution of the large bubbles is exactly what we are familiar with—in the darker part of the blue color. The small bubbles are just right, not too tightly packed, and do not give a disorderly feeling. The plaques are typically Yuan and the flare/dripping on the left even has a small breakaway plaque. The slightly greenish hue there tells you that the dye is of very good quality.

Figure 20

Figure 20

Figure 20 is another good photo, particularly the bubbles. Study the photo carefully, and you’ll understand what are good bubbles, what are good plaques and goof flare/dripping effect.

To finish this article, I’ll have another photo to show you the bubbles, plaques and flare/dripping (Figure 21). Look at these features and study them. There is no way a forger can reproduce the features that I have shown you in all these photos. If the ware has all these features, it is not a fake. It is not only genuine but to the date. You can be sure that it is a Yuan Blue and White.

Figure 21

Figure 21

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 5 Figure 6

Figure 6 Figure 7

Figure 7 Figure 8

Figure 8 Figure 9

Figure 9 Figure 10

Figure 10 Figure 11

Figure 11

Figure 13

Figure 13 Figure 14

Figure 14 Figure 15

Figure 15 Figure 16

Figure 16 Figure 17

Figure 17 Figure 18

Figure 18 Figure 19

Figure 19 Figure 20

Figure 20 Figure 21

Figure 21

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 5 Figure 6

Figure 6 Figure 7

Figure 7 Figure 8 IMG_8315.JPG

Figure 8 IMG_8315.JPG Figure 9

Figure 9 Figure 10

Figure 10 Figure 11

Figure 11 Figure 12

Figure 12 Figure 13

Figure 13 Figure 14

Figure 14 Figure 15

Figure 15 Figure 16

Figure 16 Figure 17

Figure 17 Figure 18

Figure 18 Figure 19

Figure 19 Figure 20

Figure 20 Figure 21

Figure 21

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 5 Figure 6

Figure 6 Figure 7

Figure 7 Figure 8

Figure 8 Figure 9

Figure 9 Figure 10

Figure 10 Figure Figure 11

Figure Figure 11 Figure 12

Figure 12 Figure 13

Figure 13 Figure 14

Figure 14 Figure 15

Figure 15 Figure 16

Figure 16 Figure 17

Figure 17 Figure 18

Figure 18 Figure 19

Figure 19 Figure 20

Figure 20