As I have said again and again, the benchmark of Yuan and early Ming Blue and Whites is the Sumali Blue dye. It has its characteristics that are quite different from the replacement dyes that were used one following the other in subsequent years. Our experience tells use that potters often used each of these replacement dyes for many years before it is being substituted by yet another dye. During the whole period when a dye was in use, the characteristics and presentations of the dye remain rather constant. For example, the blue dye used in the Chenghua period looks rather constant, except in occasions when potters would mix some Sumali Blue left-overs with their regular blue dye.

This cannot be said of the Sumali Blue dye. During the eight decades when the dye was imported, it revolved constantly, though all through those years, it retains certain characteristics that would allow us to put them in a group. In a way, Sumali Blue dye is a broad term that has a broad meaning. We must not think that the Sumali Blue used by Yuan potters is the same as the Sumali Blue of the Xuande period. No, they are not. They are very different. Even the Sumali Blue dye within the Yuan Dynasty is different, and I have shown you that. It is true with the Yongle period and the Xuande period. They can be very different, and it is of the utmost importance that we know that and that we are able to sort them out.

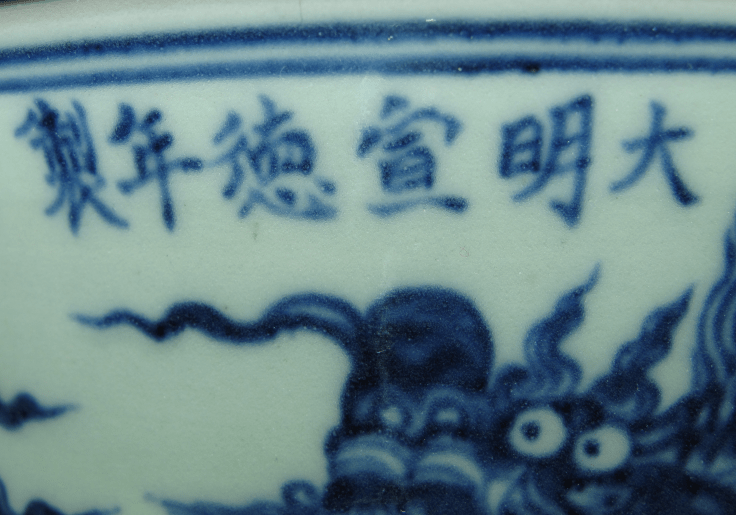

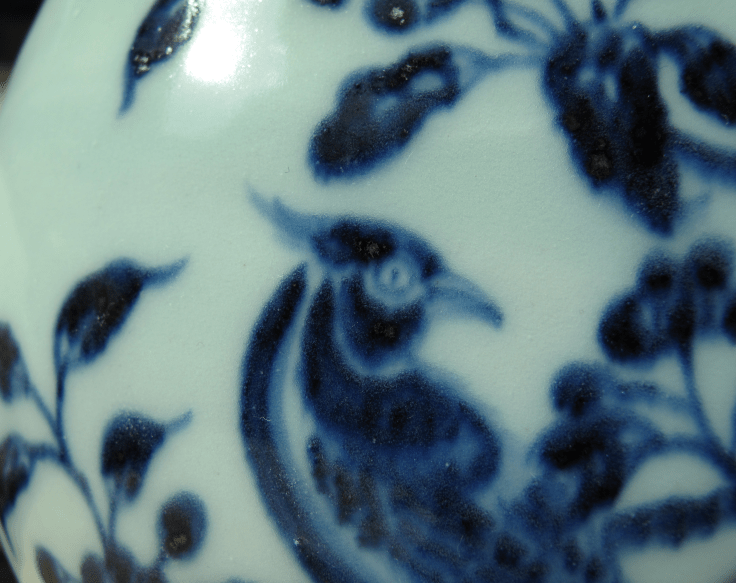

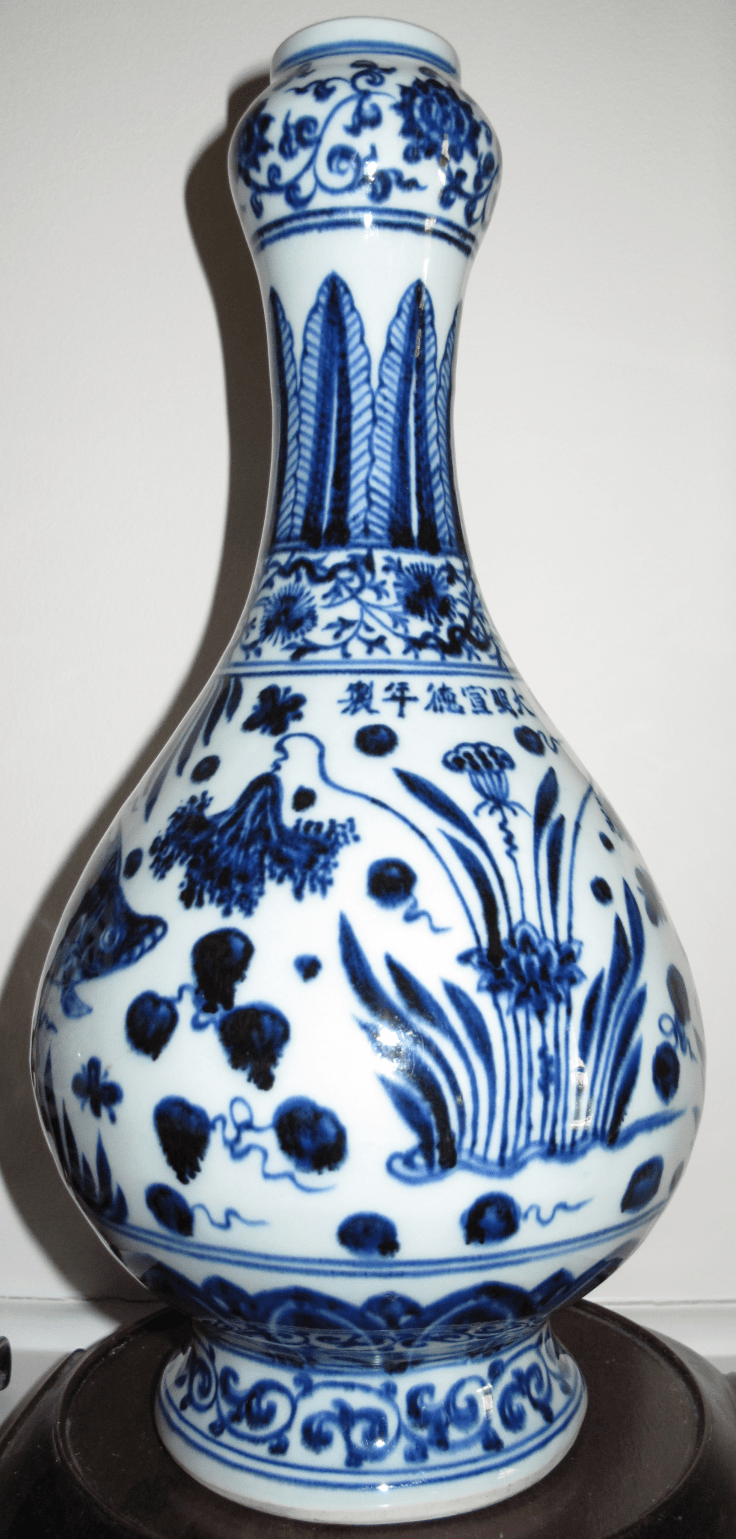

Here, I am going to show you a Bianhu of the Xuande period that potters used different Sumali Blue dye on the neck of the vase and the body itself. I have told you before that potters, in order to save cost, would use different grades of blue dye on the same ware. Here is a good example (Figure 1). This Bianhu measures 12 5/8 inches tall, 9 5/8 inches wide and 6 1/2 inches thick. As the measurement indicates, its bulging on both sides is more prominent than a regular pilgrim flask.

Figure 1

Figure 1

A look at the photo and you can tell that the neck and the body are of a different shade of blue. Common sense will tell us that the body is the center of attraction. Look at the choice of the potters. They picked a nicer color for the body and dragon, even though in so doing it must be more expensive. That is to say, the potters believed quality comes before cost. The area of the neck is substantially less than the body, and by choosing a dye pigment that is of a lesser quality, the saving in terms of cost should not be much. At least, that is how we now look at it. But if we look at the matter from another angle, when the dye pigments were really expensive, as we are constantly told, such a move still means something in economic terms. And we need to have some faith in the rationality of the potters in their choices.

The important issue here is that we are given the opportunity to study two different kinds of Sumali Blue dye pigment in one single ware, allowing us to come to the conclusion that the variation of the Sumali Blue dye can occur within a very short period of time. It would not surprise me that any batch of dye pigment imported is somewhat different from a previous batch.

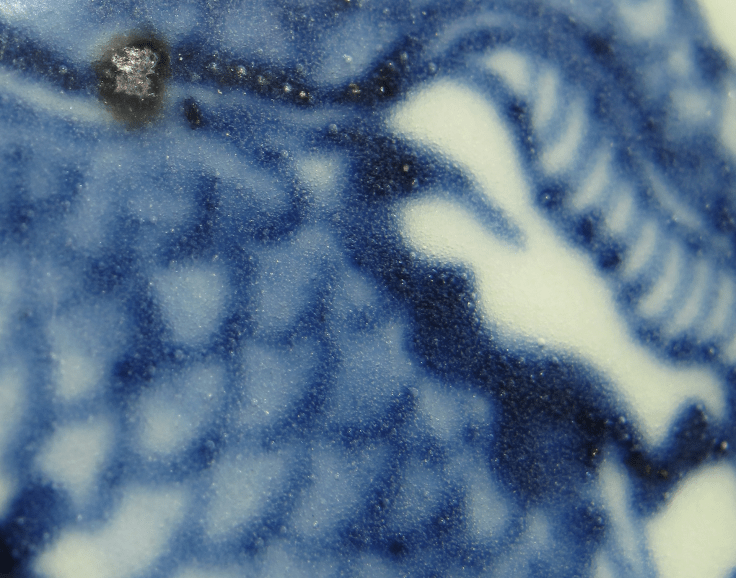

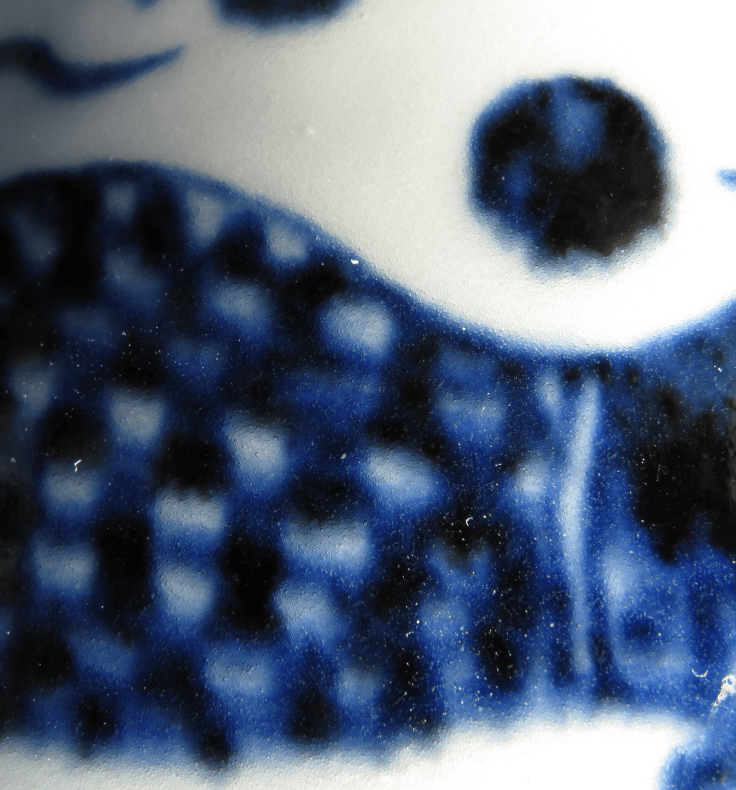

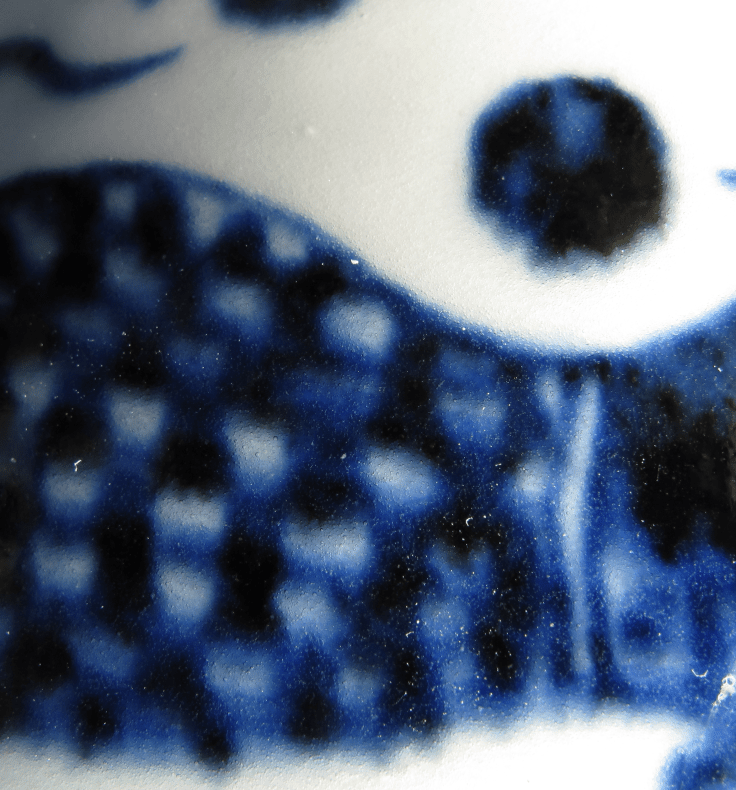

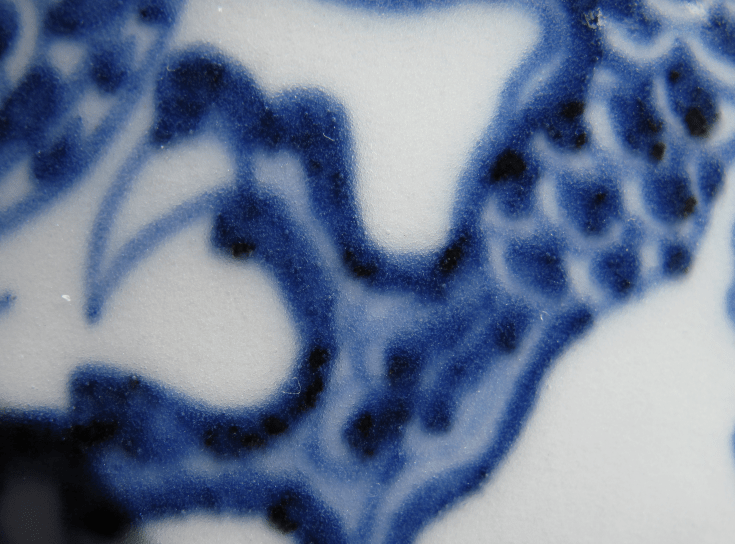

I have been telling you that there are certain very general differences between Sumali Blue of the Yuan period and the Yongle and Xuande periods. It will not be true in every case, but generally speaking, this is a good guide line. There are a lot more plaques in Yuan B & Ws, and they are thicker and appear to be more coarse. Plaques in Yongle period are less abundant, and many a time, the edges tend to be spiky. In Xuande B & Ws, the plaques become a lot thinner, and in some wares, they appear only as some patches of a darker bluish hue, and reflections are only obvious when seen under sunlight in a particular angle. That is to say, we often have to tilt the ware in different direction in order to see the reflections.

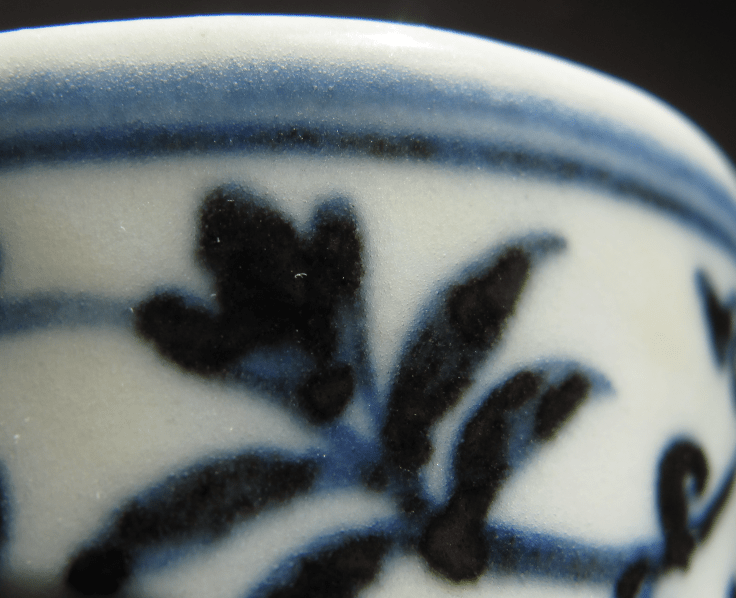

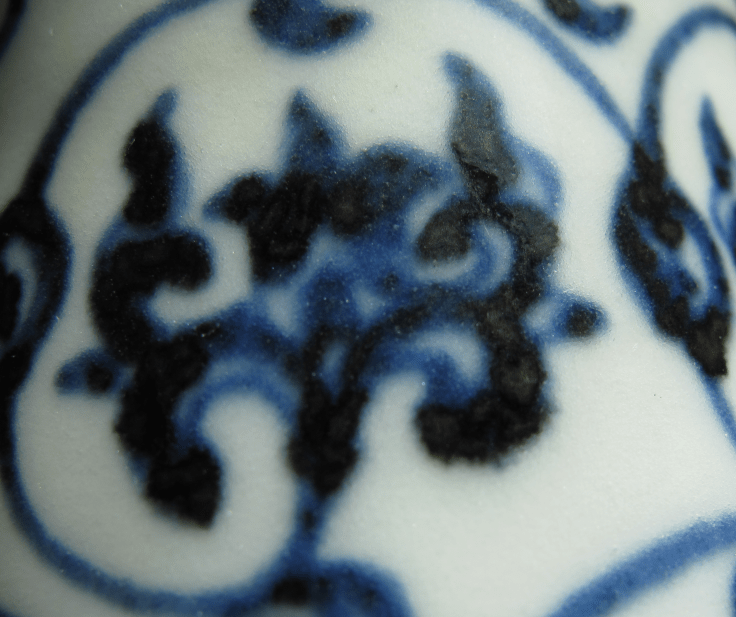

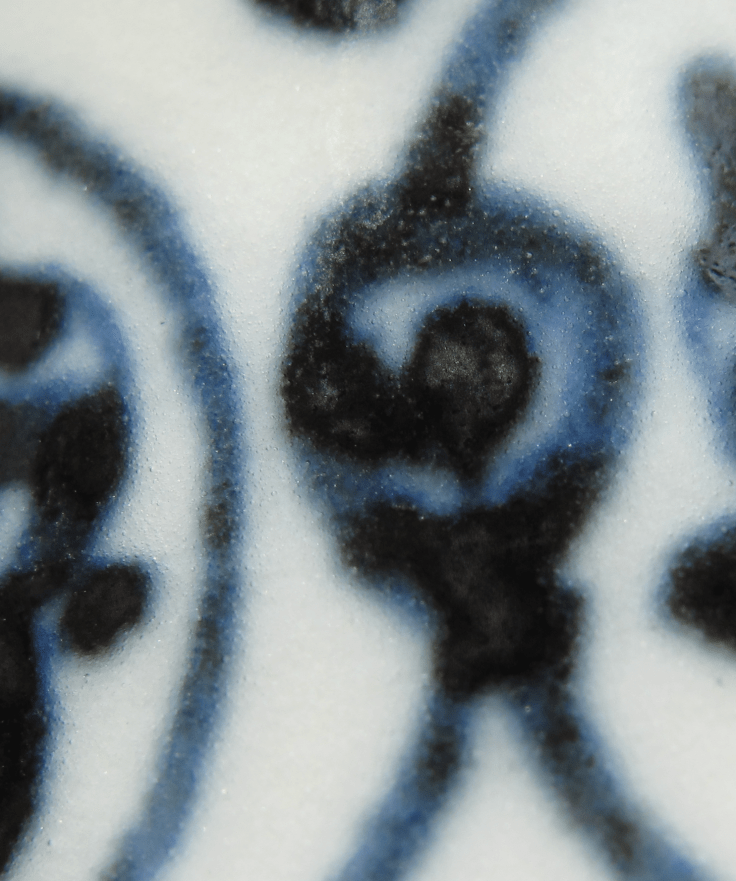

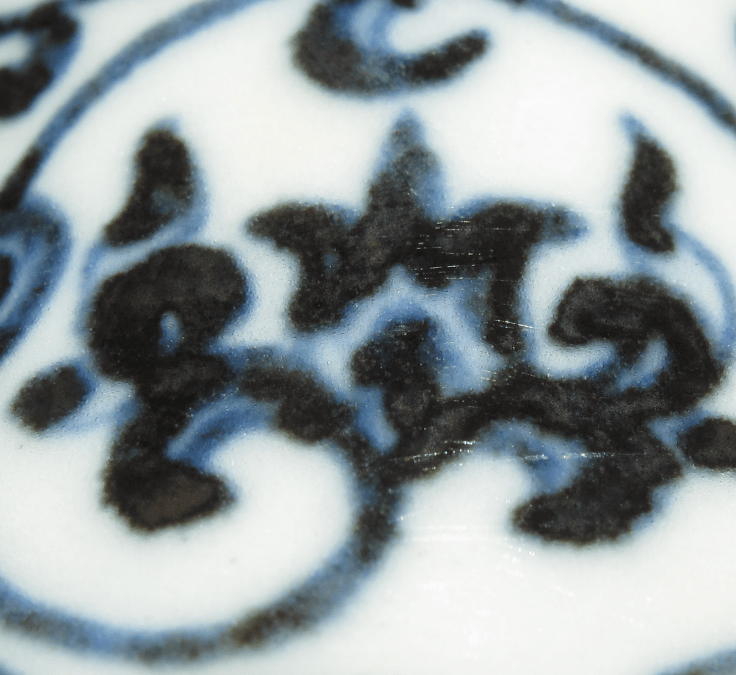

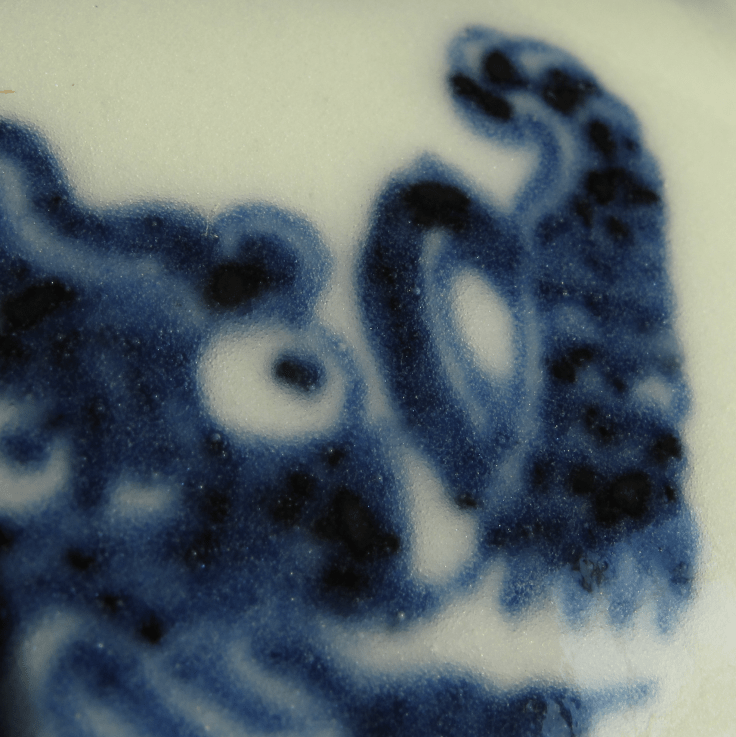

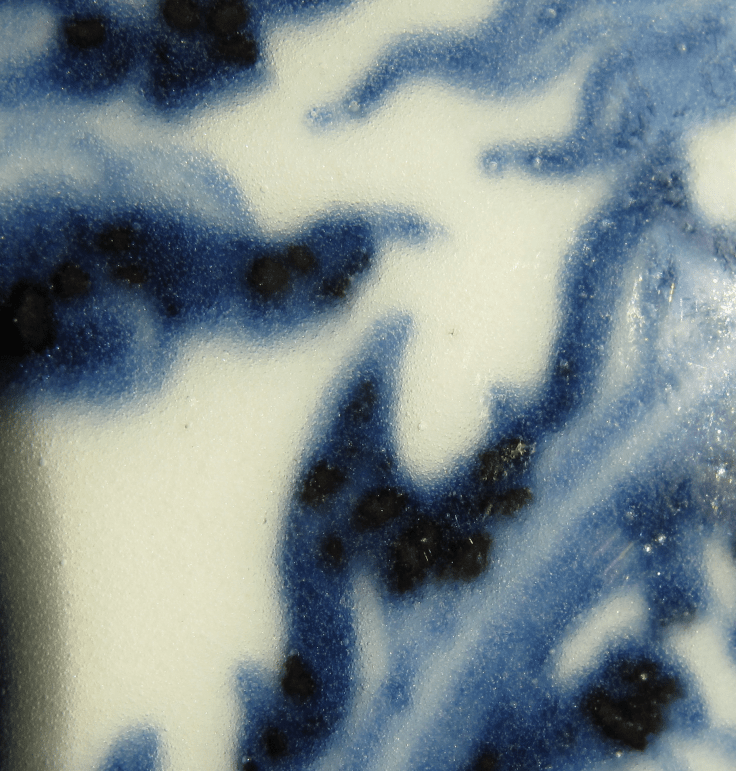

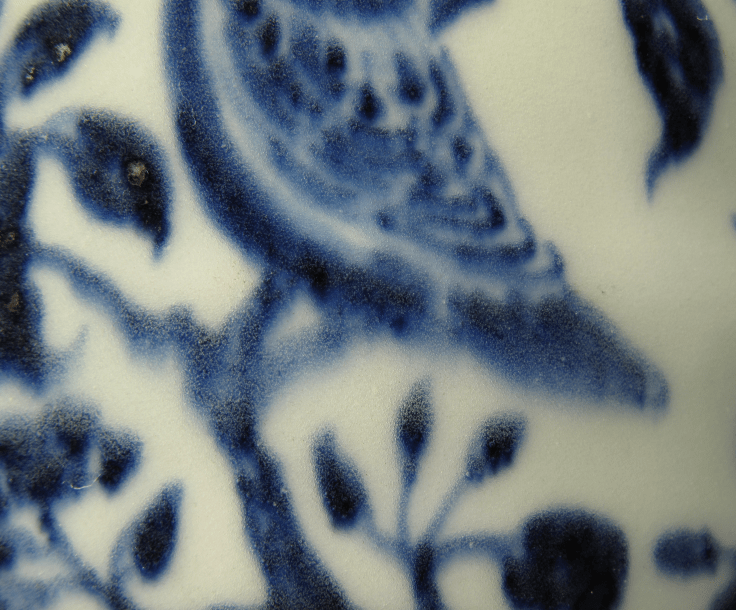

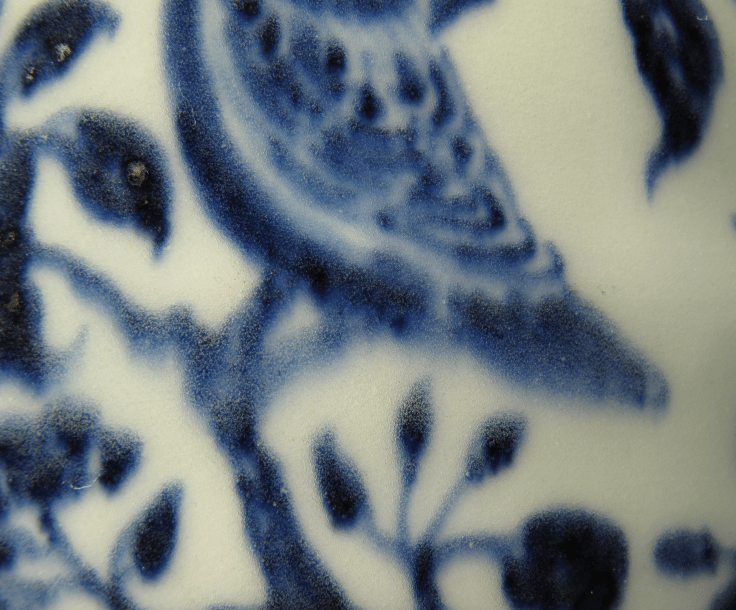

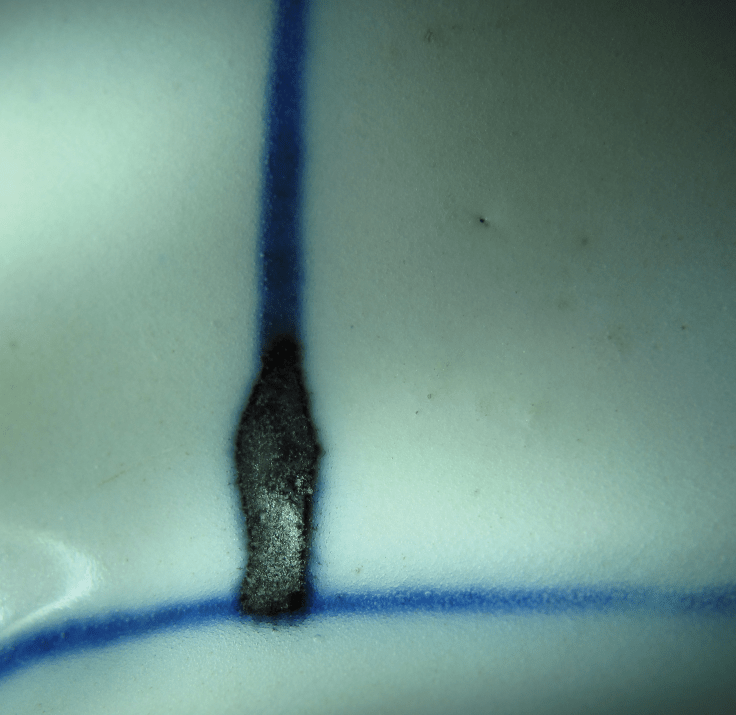

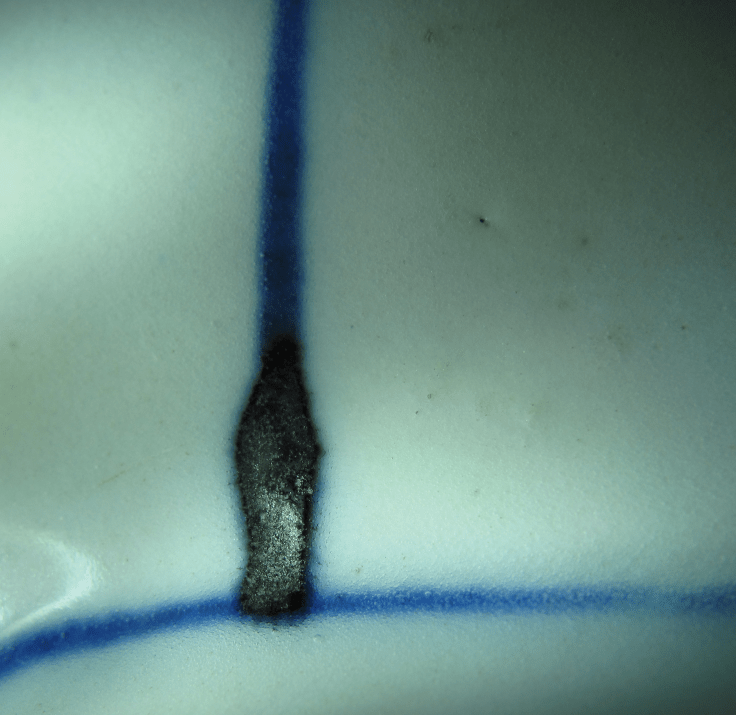

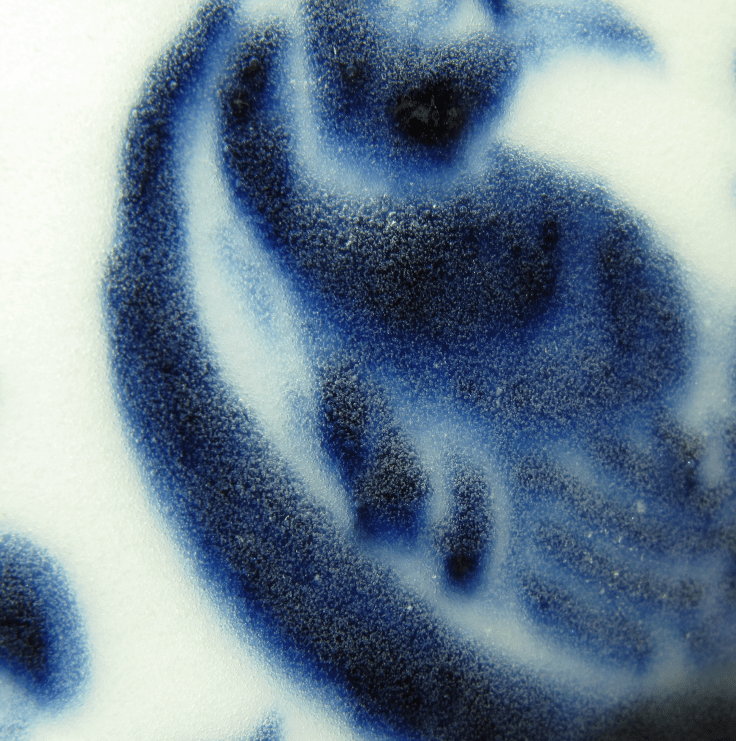

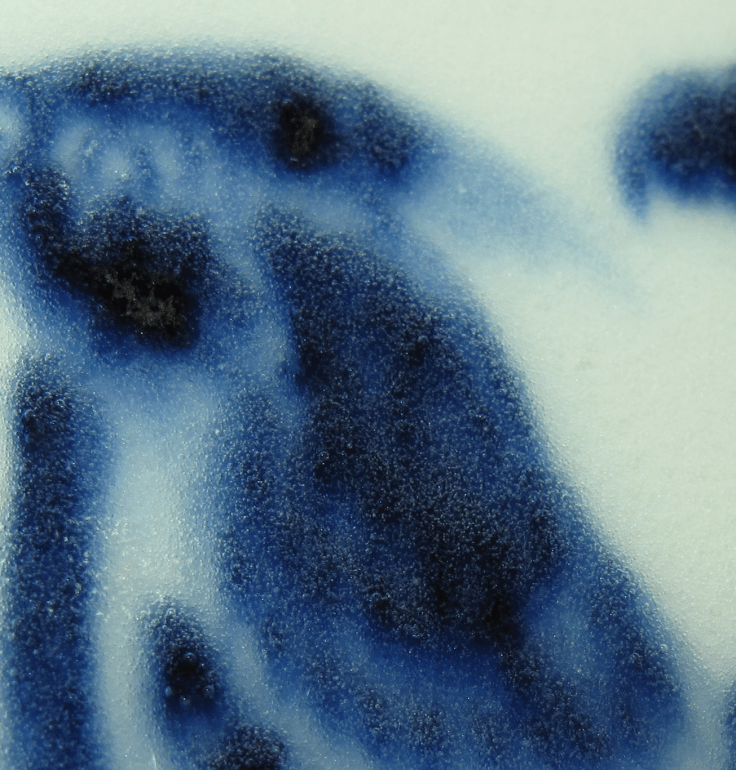

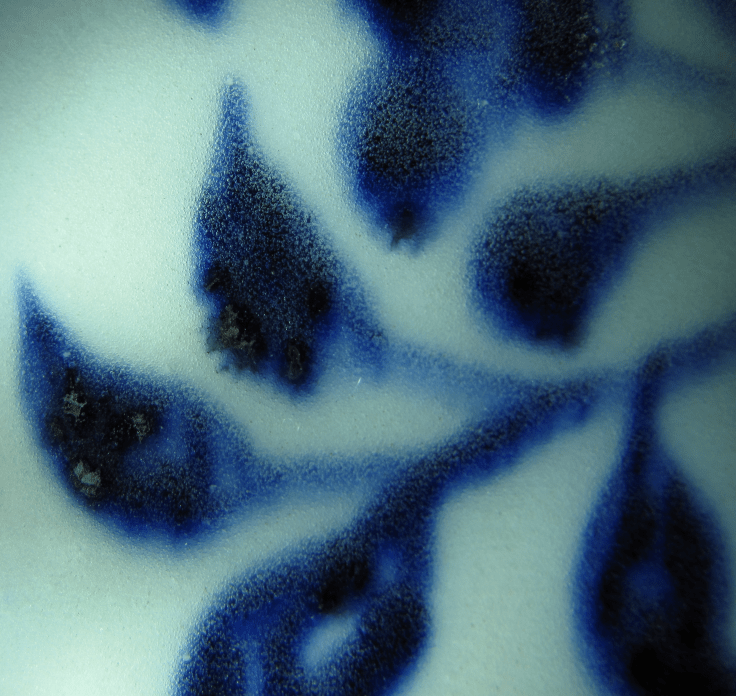

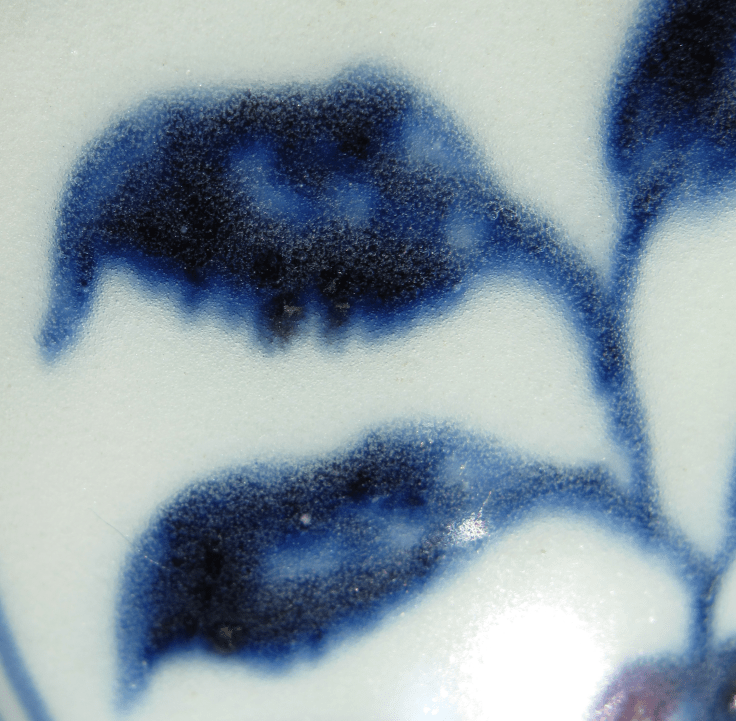

Now, let us look at the two different dyes in this Bianhu.

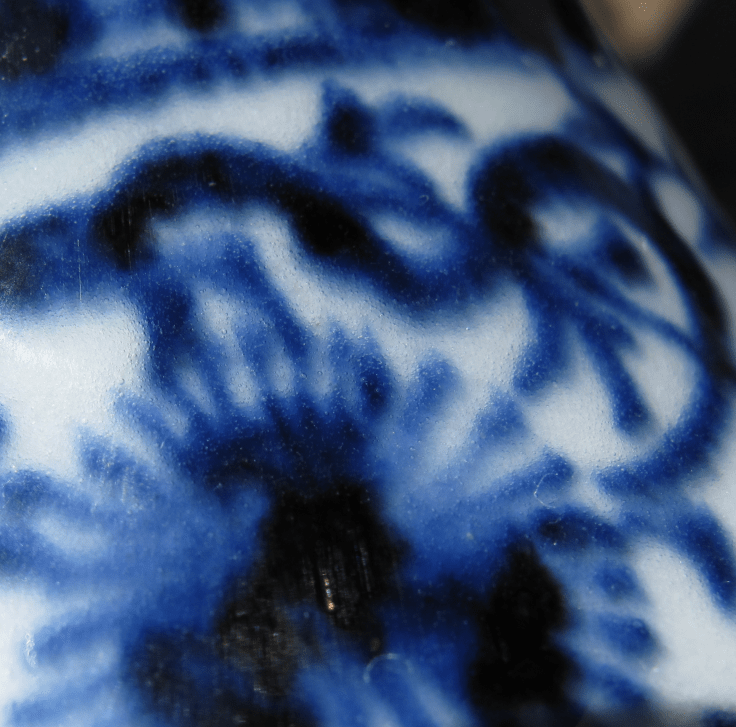

Figure 2

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 8

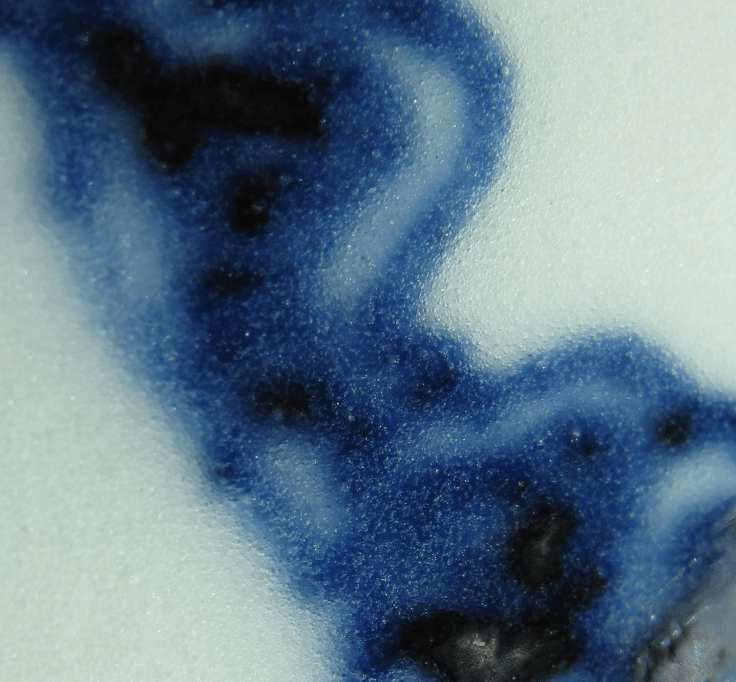

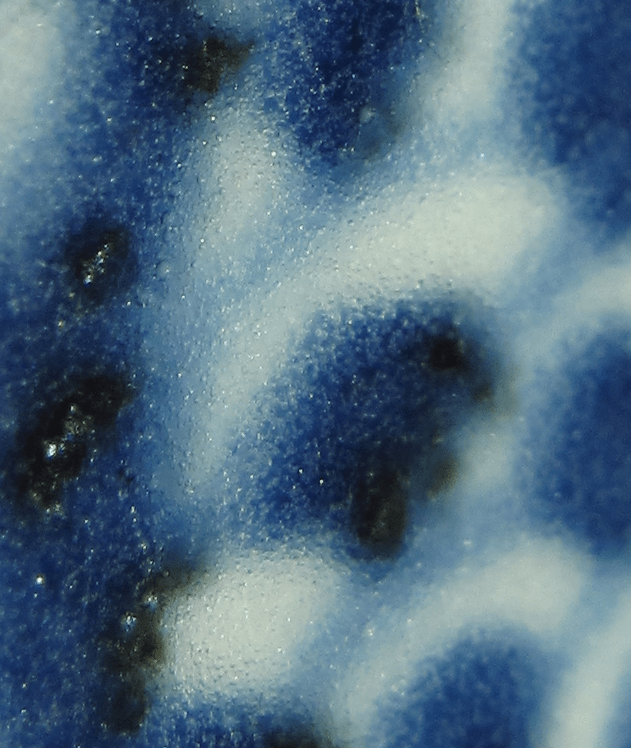

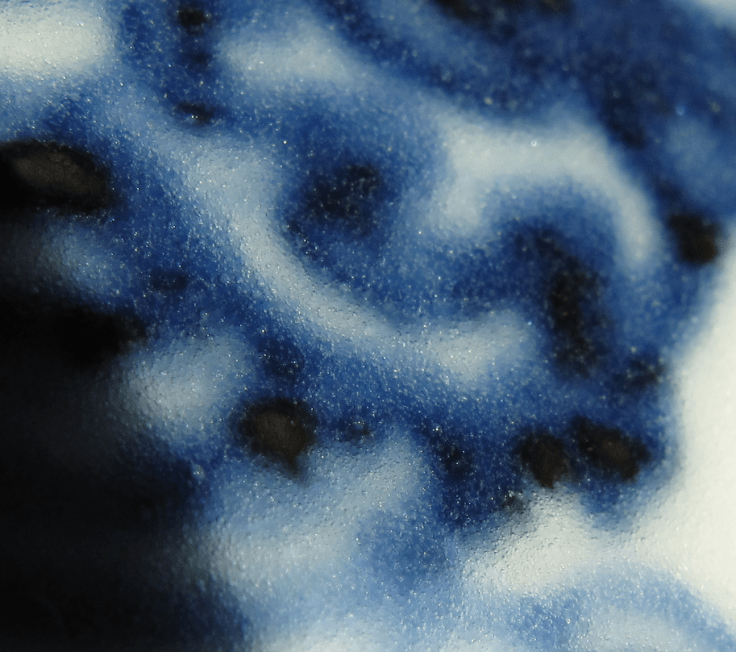

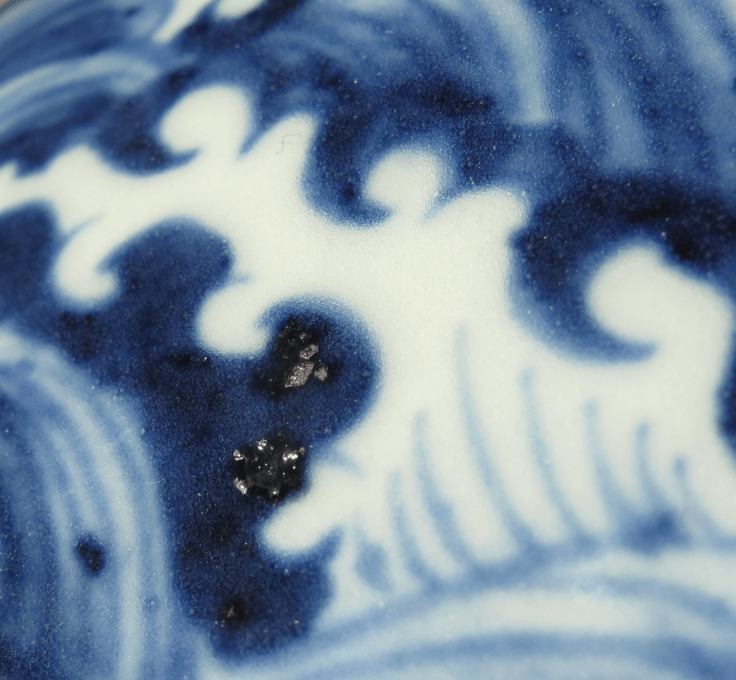

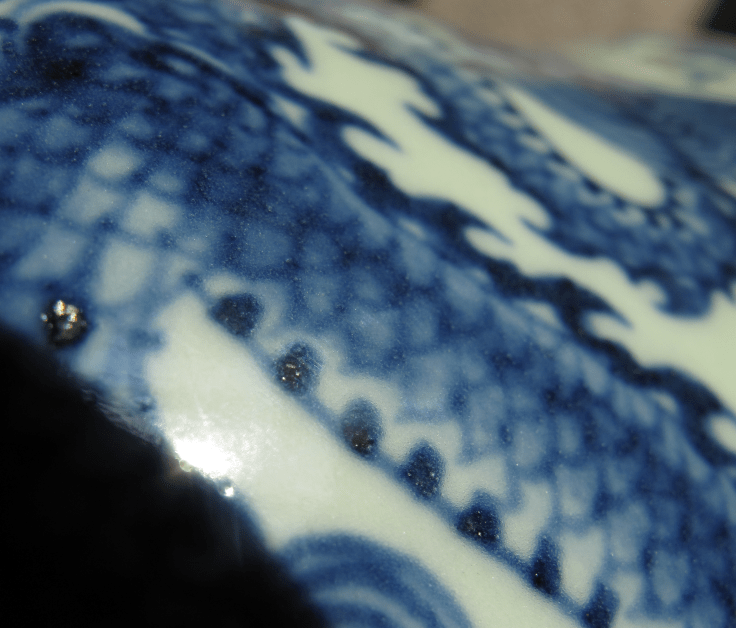

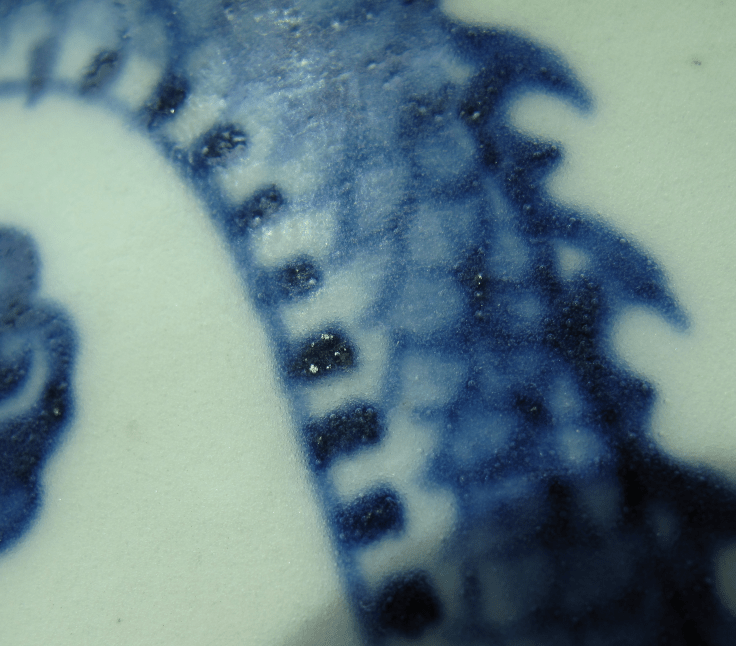

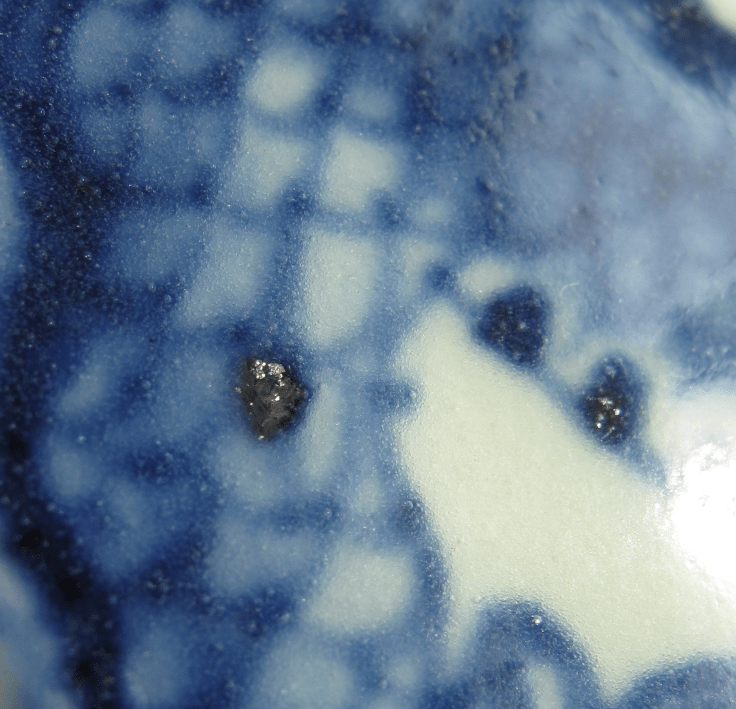

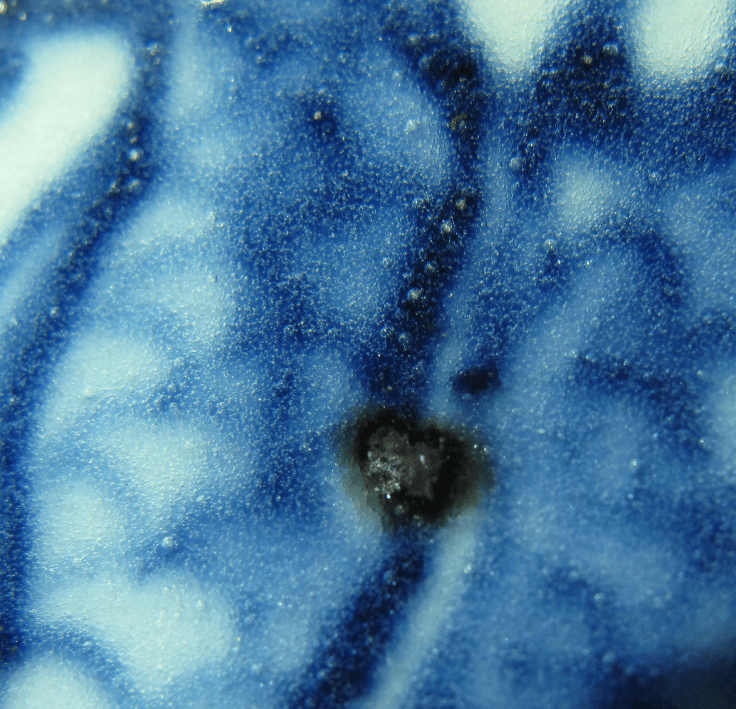

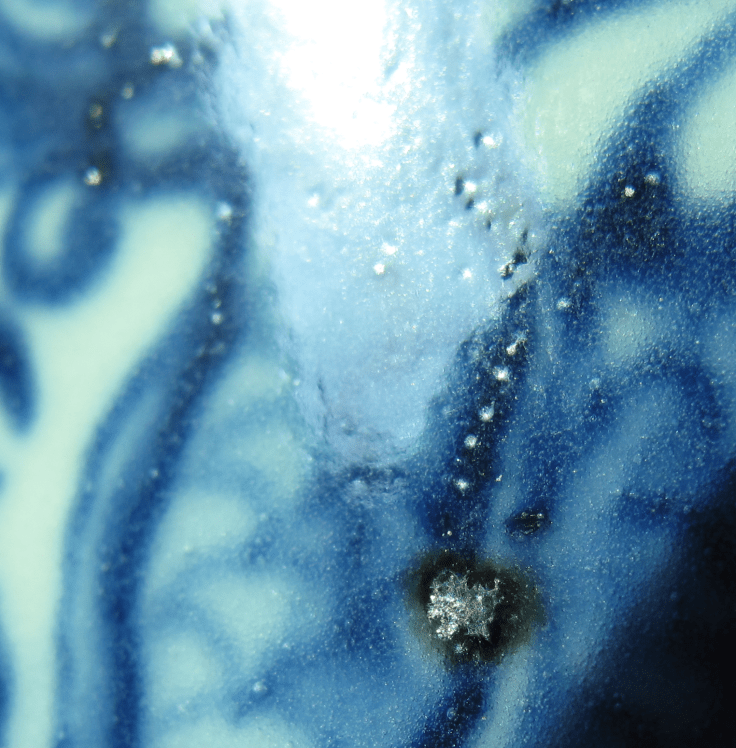

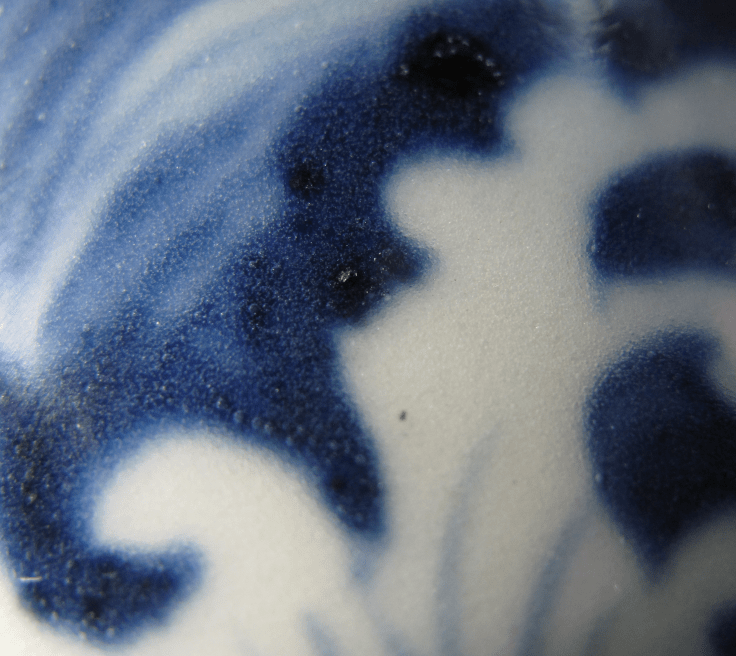

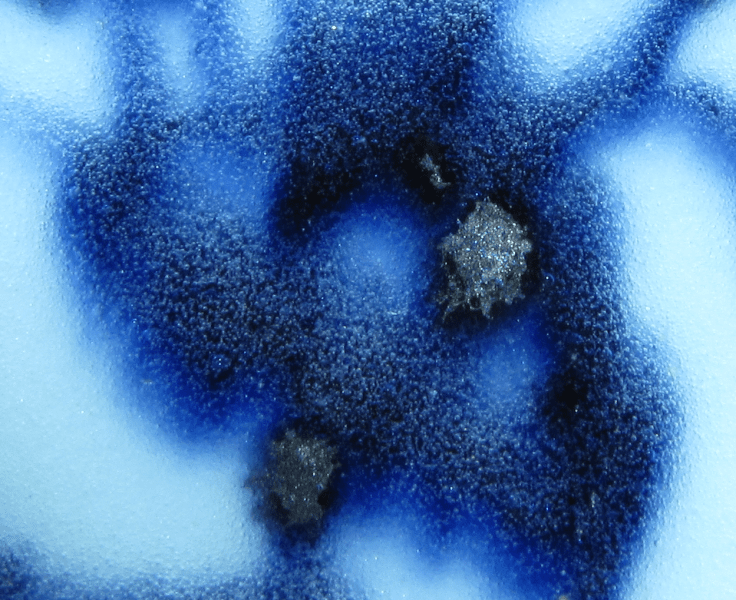

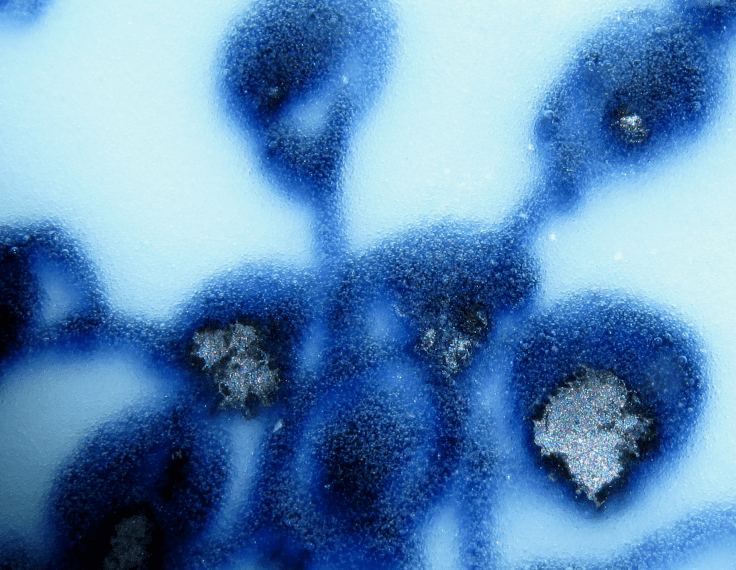

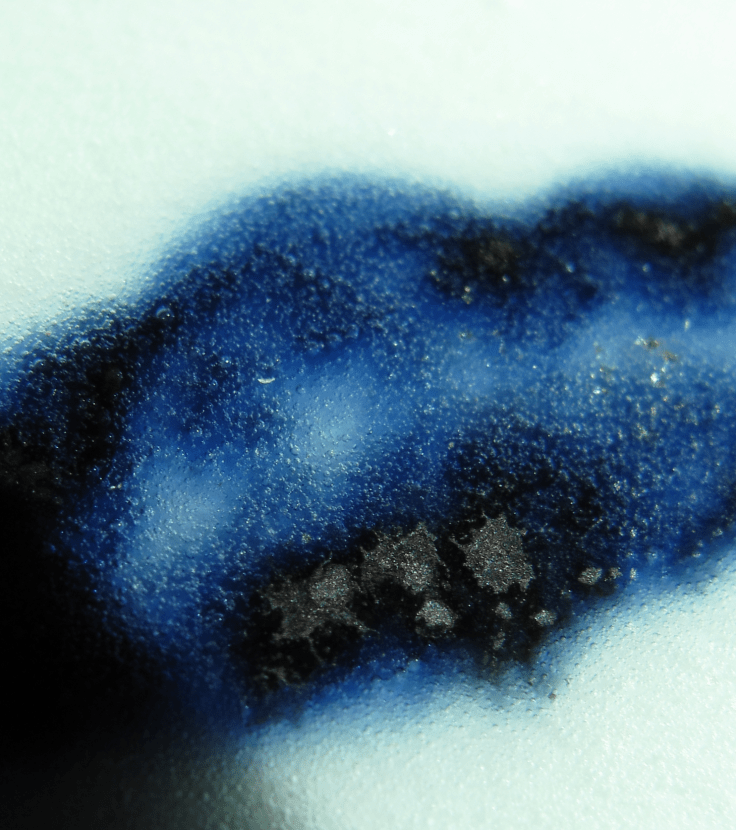

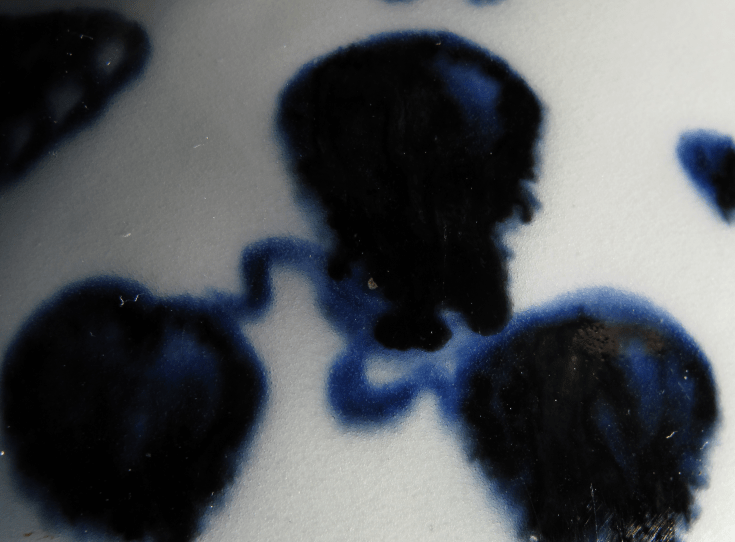

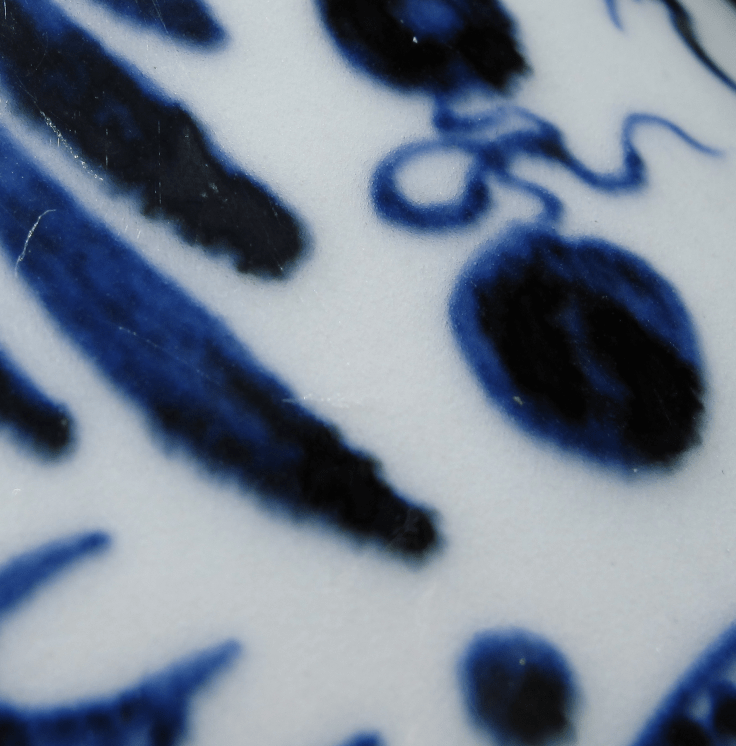

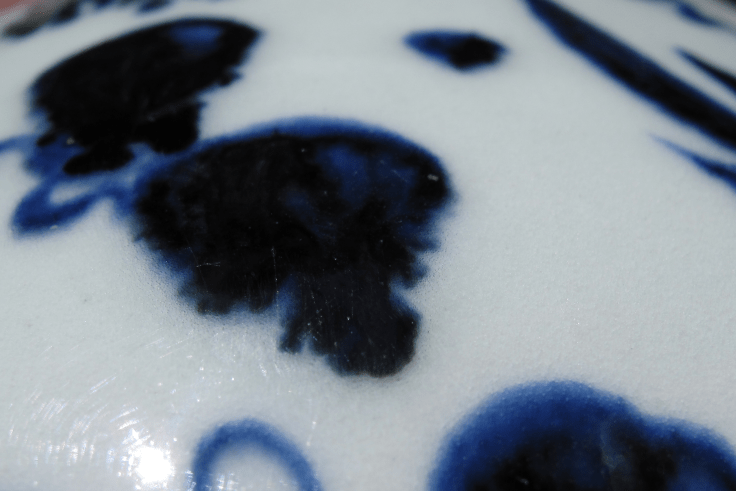

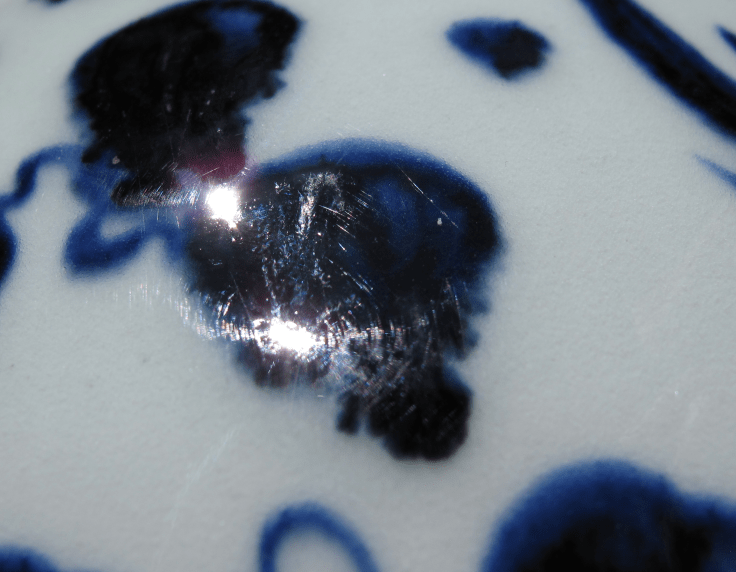

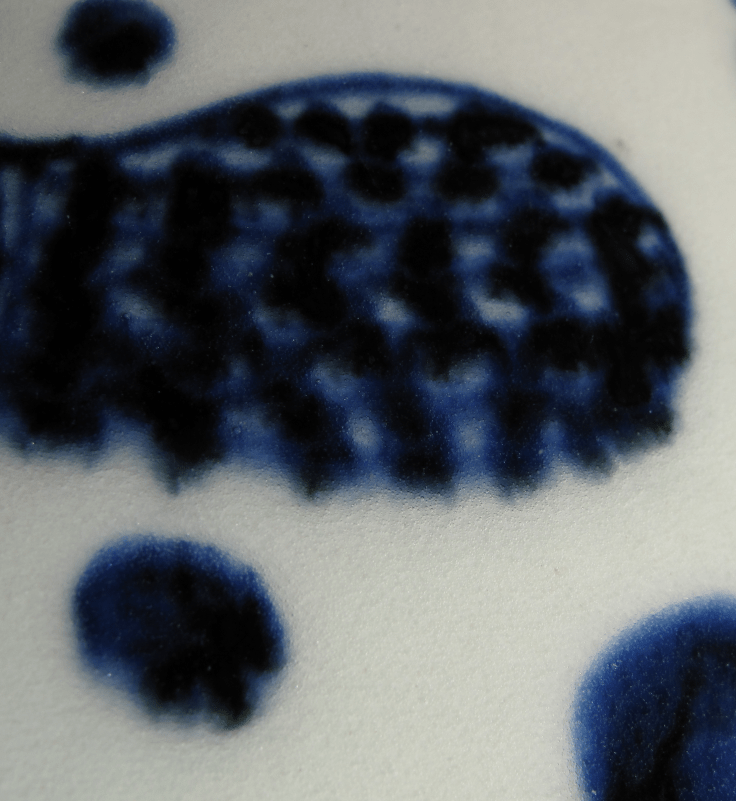

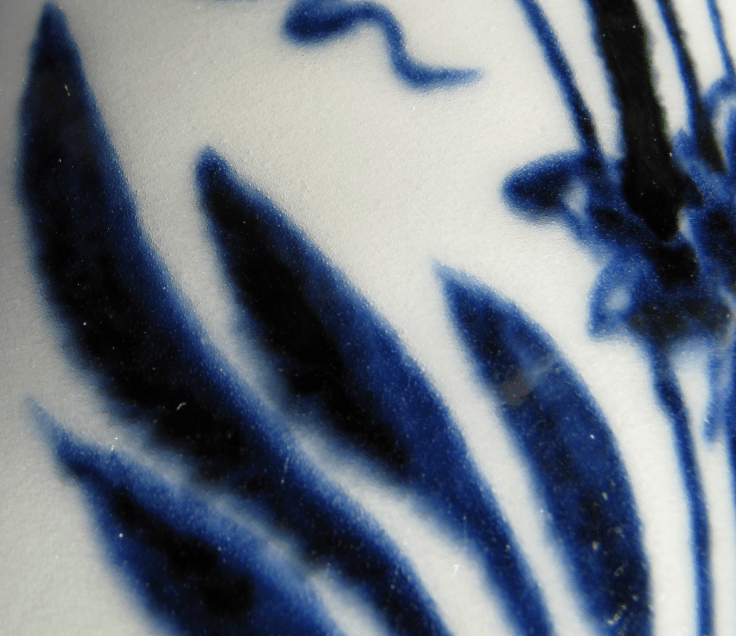

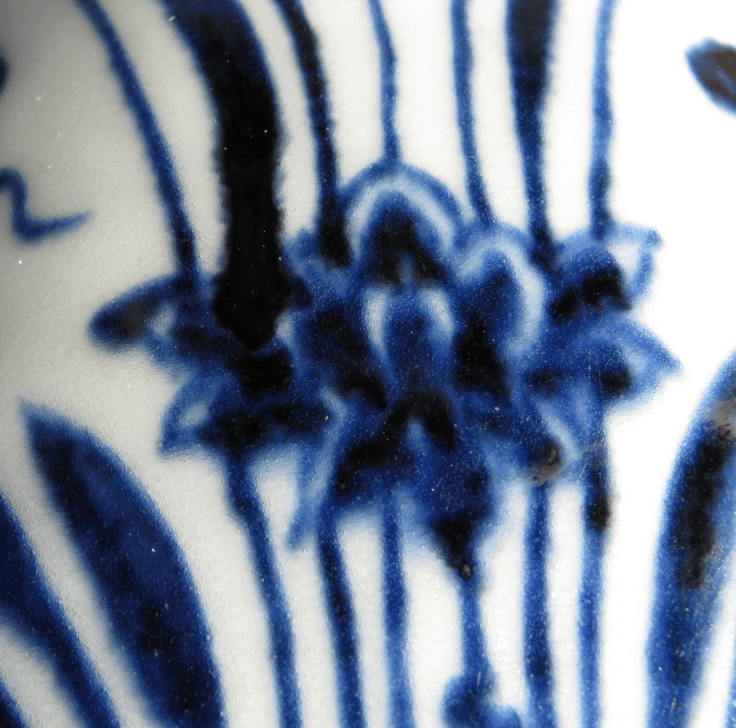

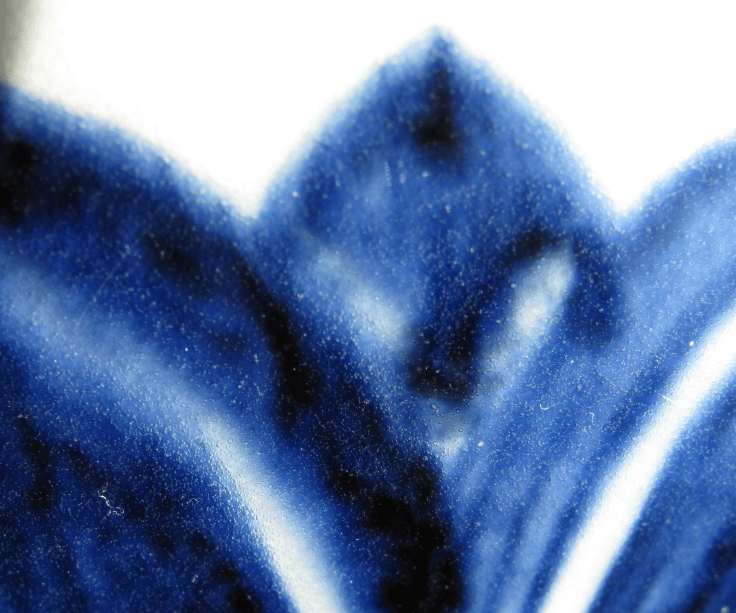

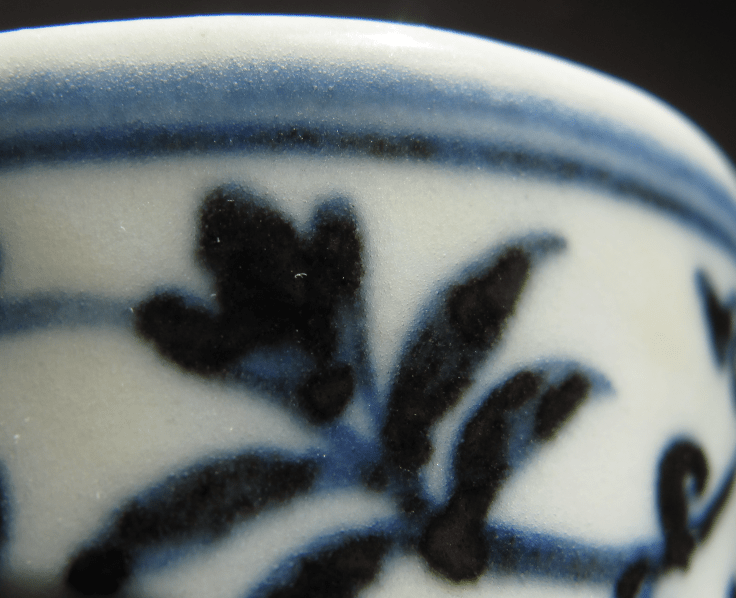

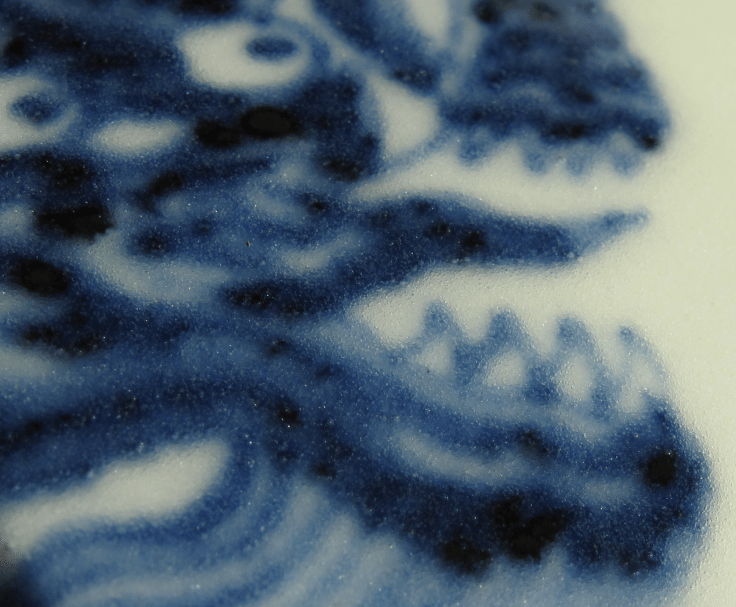

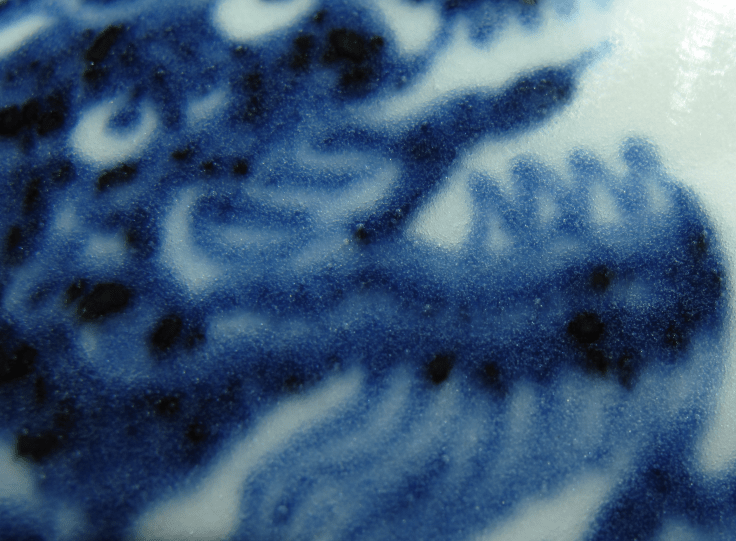

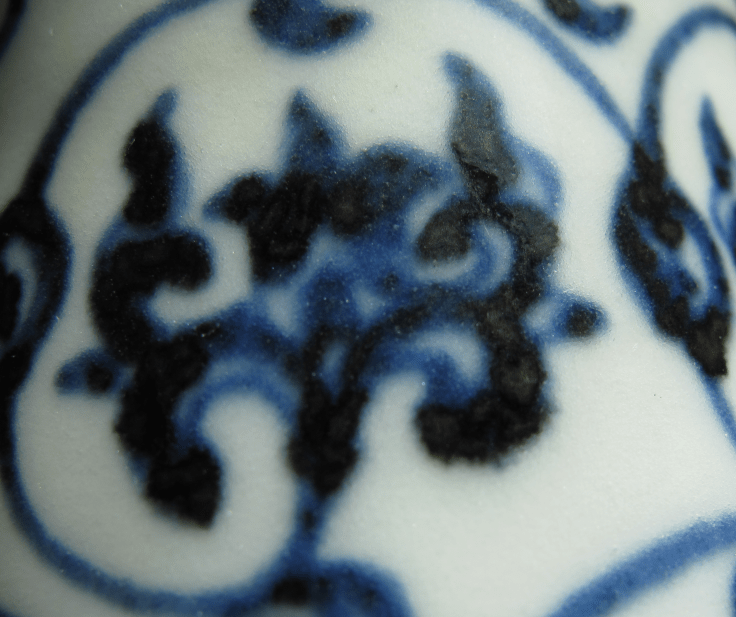

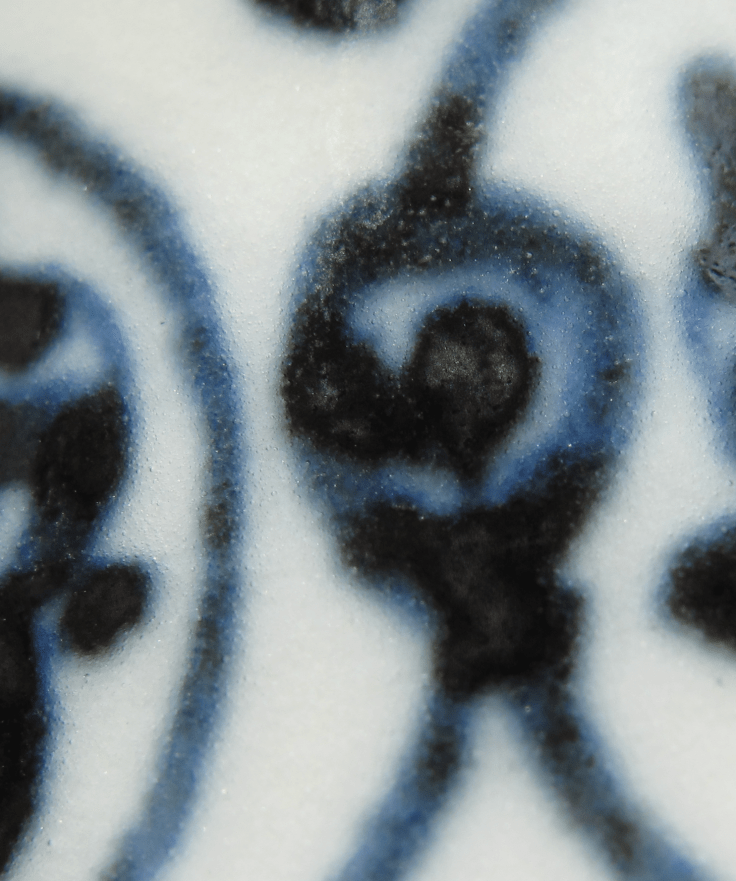

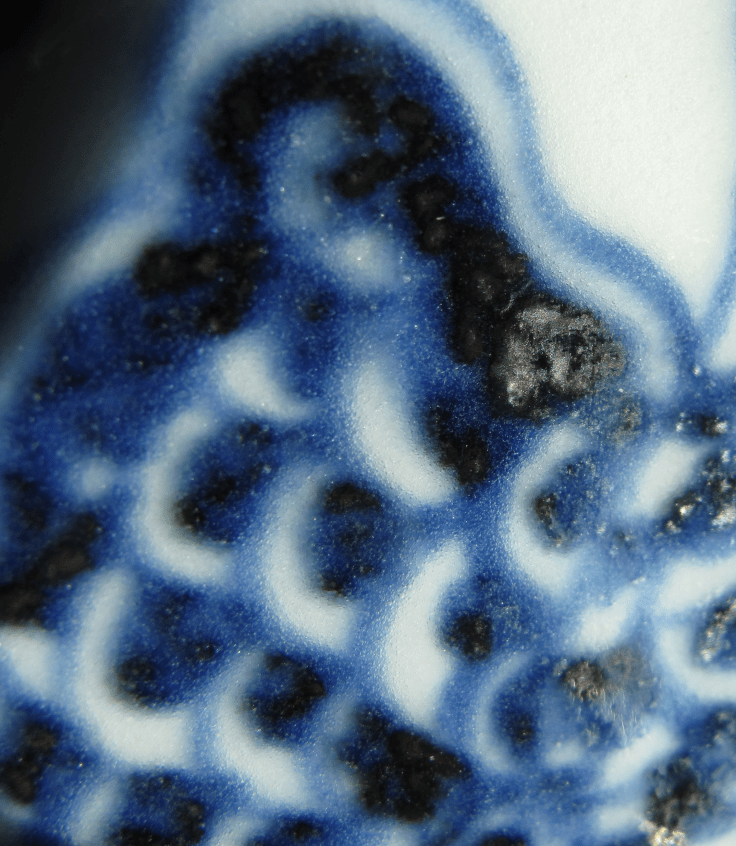

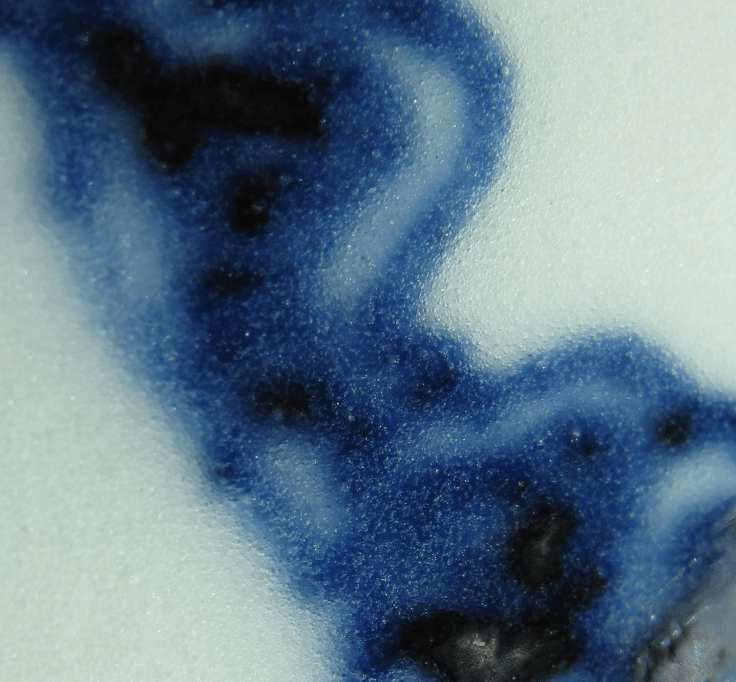

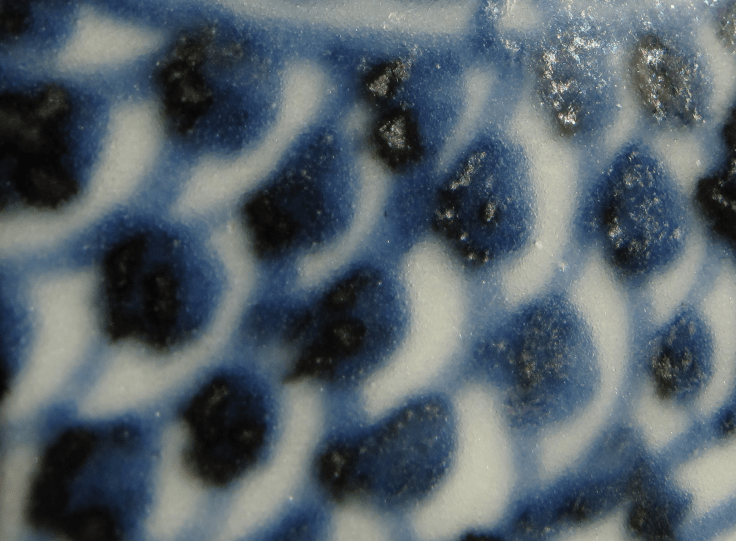

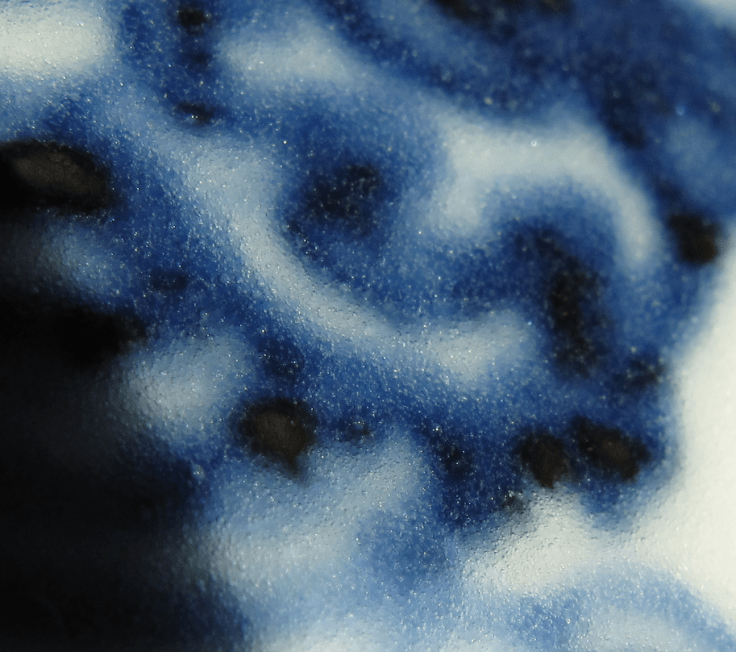

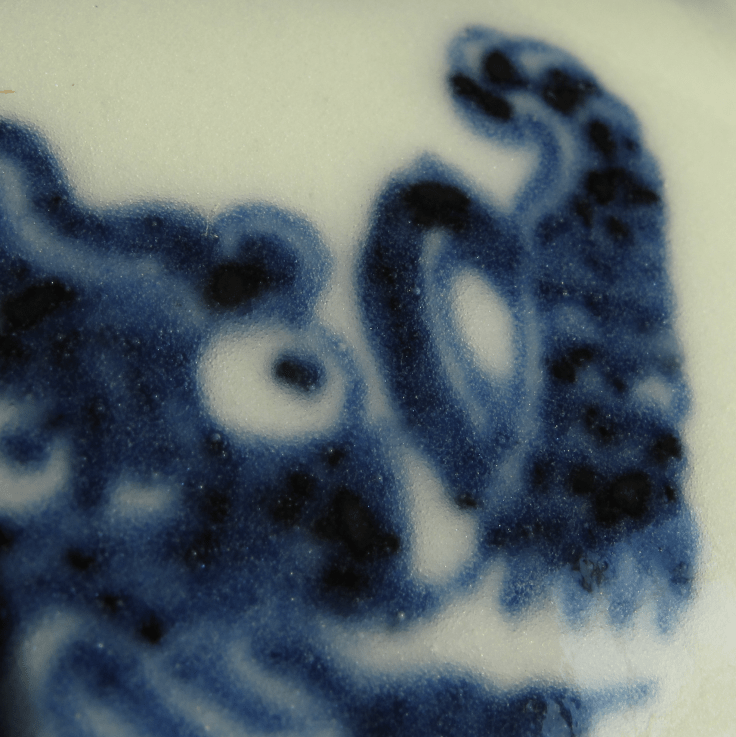

A look at Figures 2-4, which are from the neck, and Figures 5-8, which are from the body, you will note the differences between the two dyes. They are taken under daylight. There are a lot more plaques in the neck, but they are very different from those found in the Yuan wares. In the Yuan period, as you will remember, the plaques often sit a in small pool pf dark blue color, and the plaque itself is coarse and shiny reflections are common. Here, the plaques are mainly blackish. They might be sitting in a pool of similarly blackish color, of slightly different shade, but often the edge of the plaque is not clearly defined. If you are going to look more carefully by enlarging the photo, many a time, the plaques are in fragments that seem to merge with the surrounding black color. They are much thinner than those in the Yuan period. And you need to look at the texture of the plaque, they are quite different. By looking carefully, and at more of the plaques, you will have your own conclusion how they look like.

My own feeling is that plaques here in the neck have some very basic differences in the ingredients. A plaque, as I see it, has two components. A muddy layer at the bottom and a metallic layer that floats above it. The metal must be a light metal, like aluminum, that has a specific gravity that is lower than the glaze, so that it floats above it. On occasions, the metal might mix with the muddy components, so that the mixed component does not go up completely, but floats halfway in between the top of the glaze and the bottom of it. Here, both components—the mud and the metal, are blackish, and often it is difficult to tell which from which. However, on careful examination, one can still tell, though the demarcation on certain instance is blurred. One reason for this is that here the metallic content is not high enough for it to form a well defined aggregate, allowing a thin tin-foil like layer to be formed. It will take a physicist to tell you what is the critical mass of the metallic content that would allow it to form a tin-foil like structure, but it is suffice to say here that that layer is not well formed, and a reflective layer is absent, so that the appearance is just blackish, with a different shade for the muddy part and the floating metallic part.

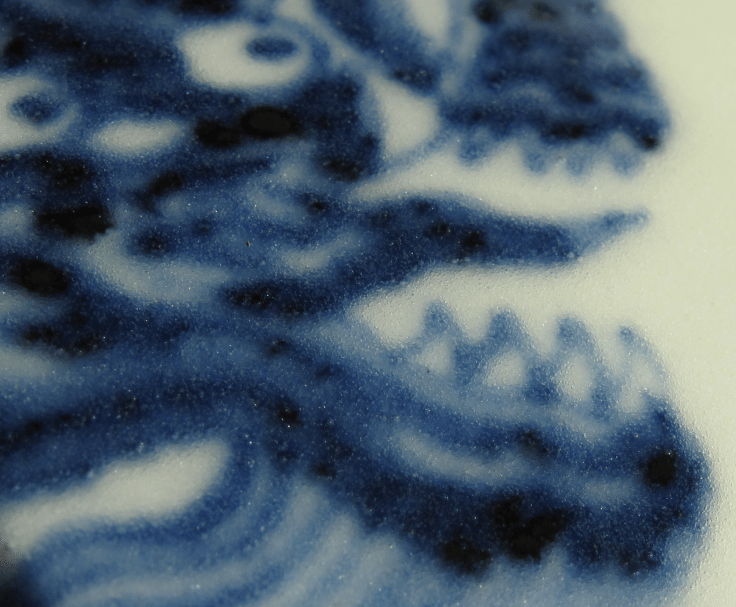

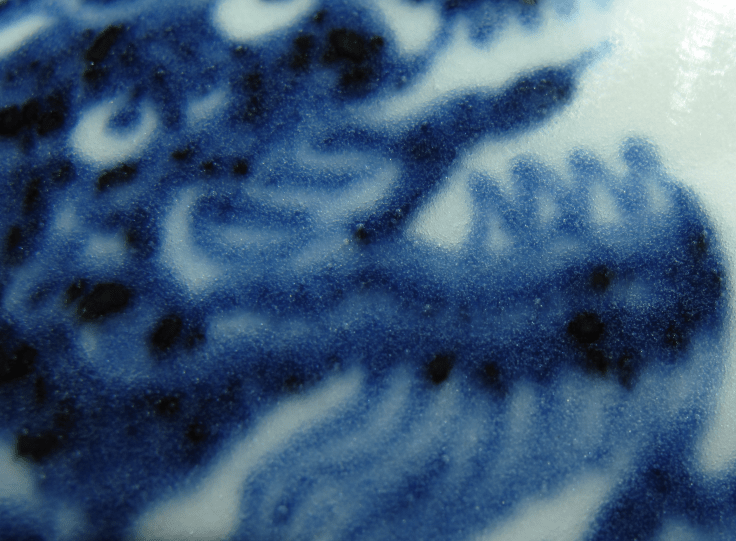

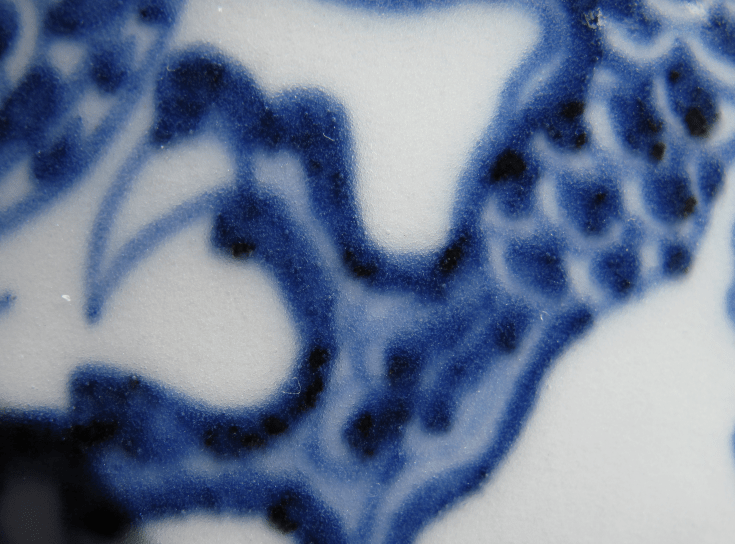

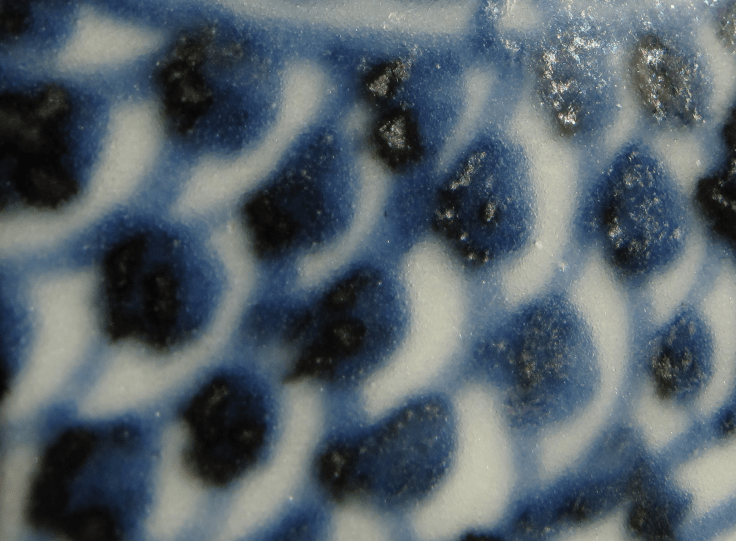

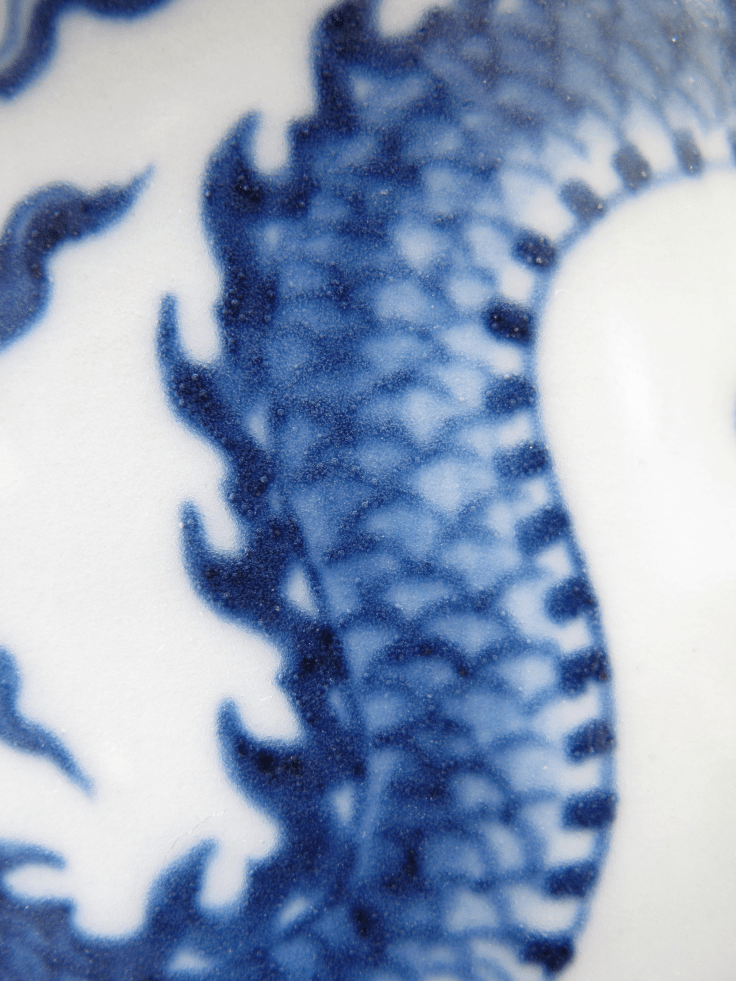

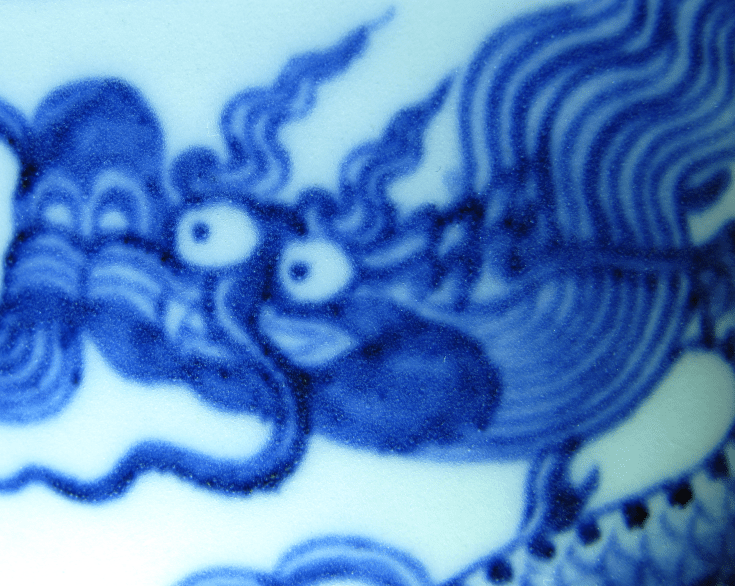

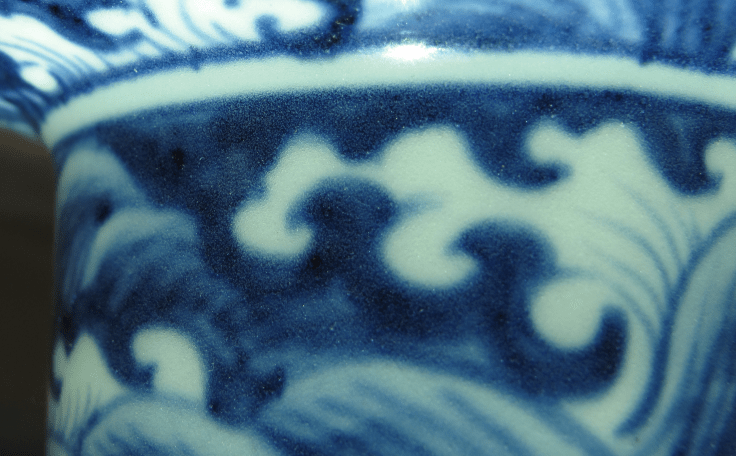

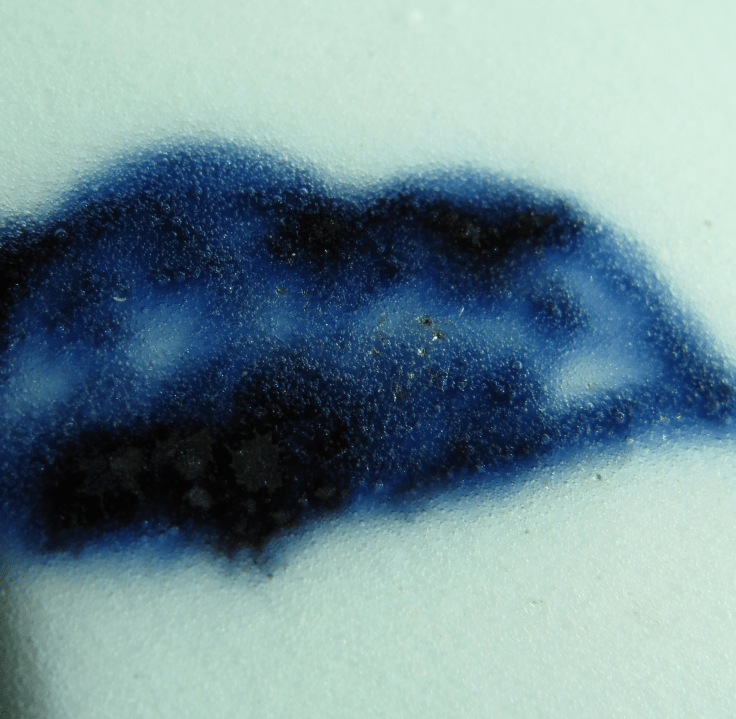

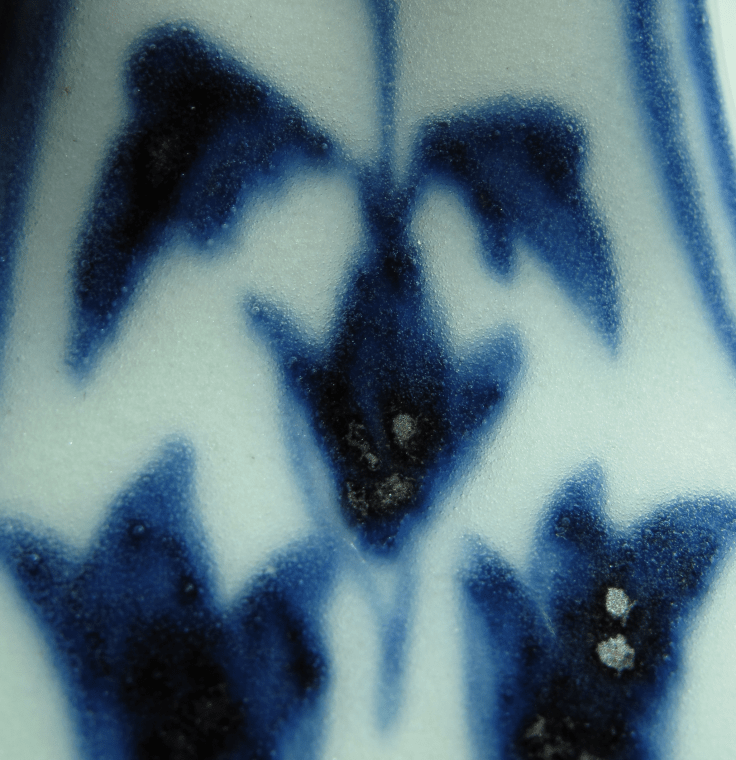

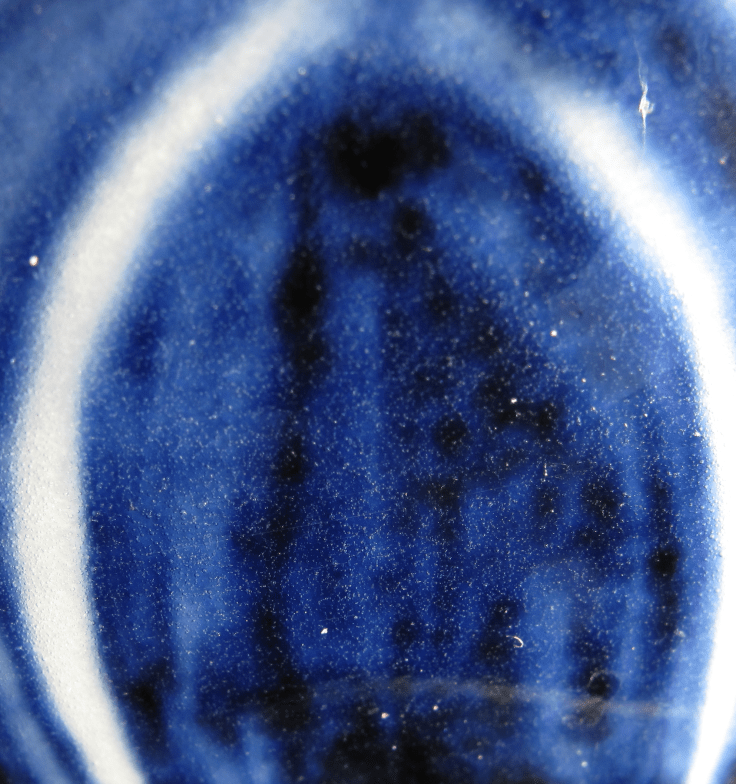

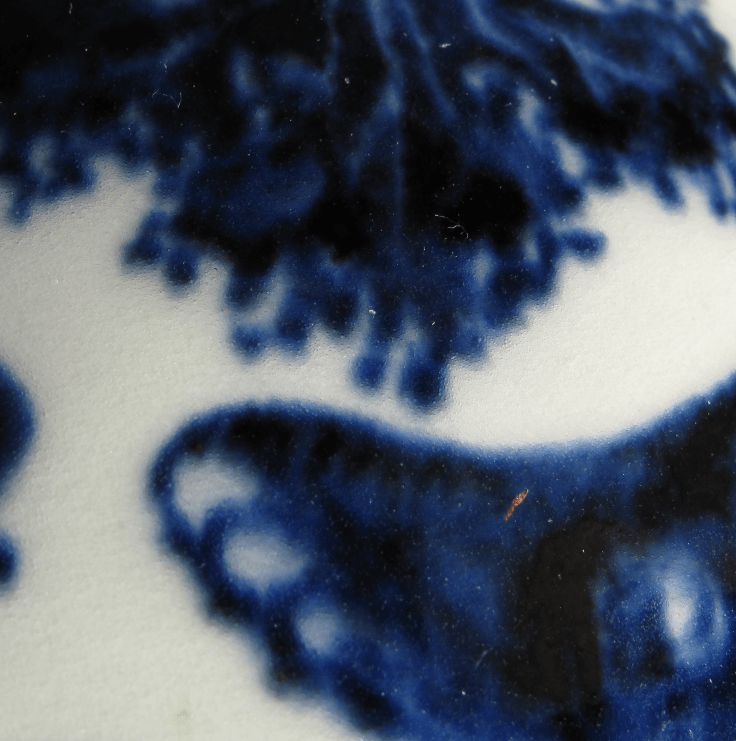

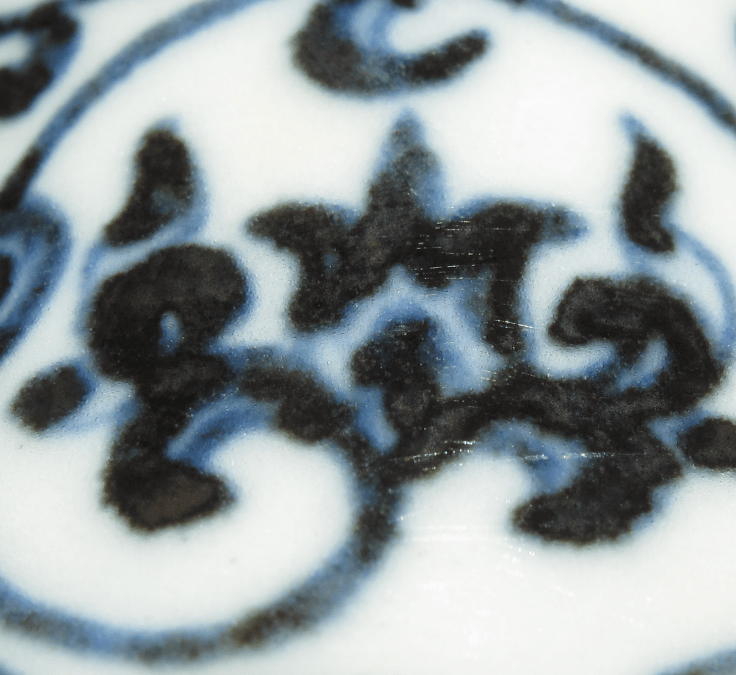

The plaques in the body are different (Figure 5-8). They are much less abundant, and their structure tends to resemble more of those we have seen in the Yuan wares and Yongle wares. They are blacks patches sitting among some dark blue colors. But they are not well formed plaques except in certain small areas, another indication that the metallic content is low. But in all these photos, if you look for them. you can see flares and drippings. By now, you should be convinced that the flares and drippings are from the muddy part of the plaque. However, the plaques show some clear differences in their looks between those in the neck and those in the body. Just compare Figure 2 and Figure 5, and you will understand what I am trying to say.

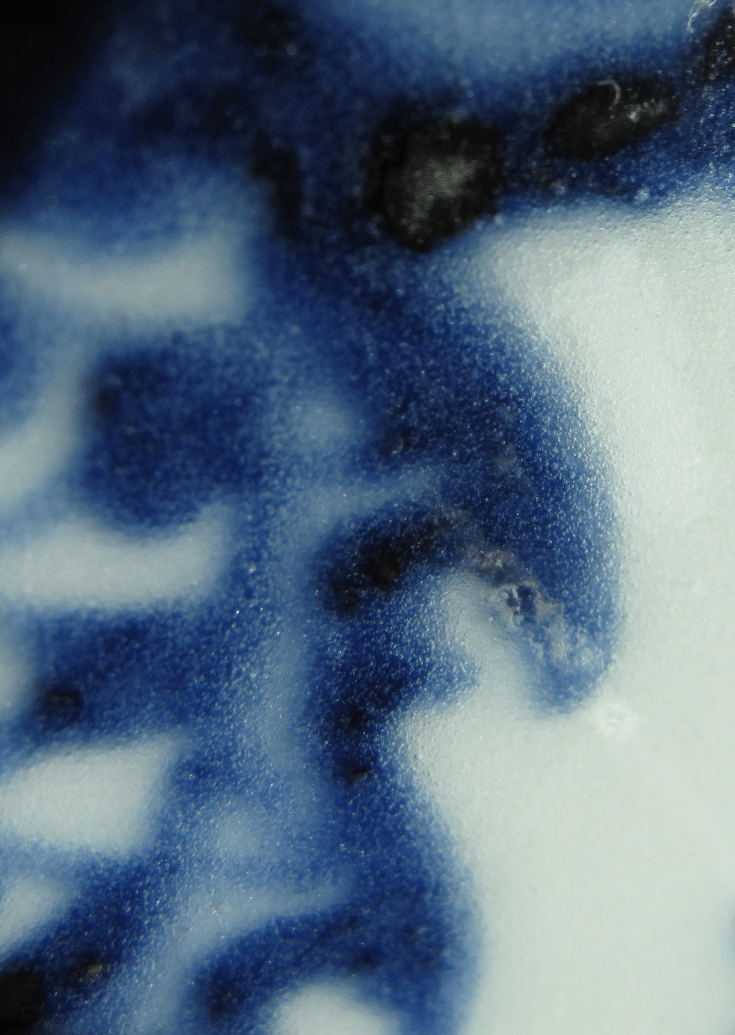

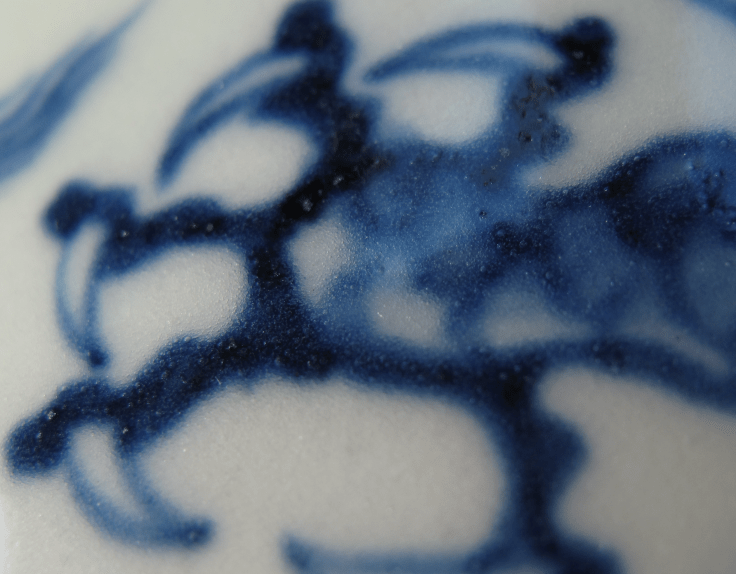

Now you may want to know how the plaques look like when the photos are taken under direct sunlight, or in some cases, under direct LED light.

Figure 9

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 17

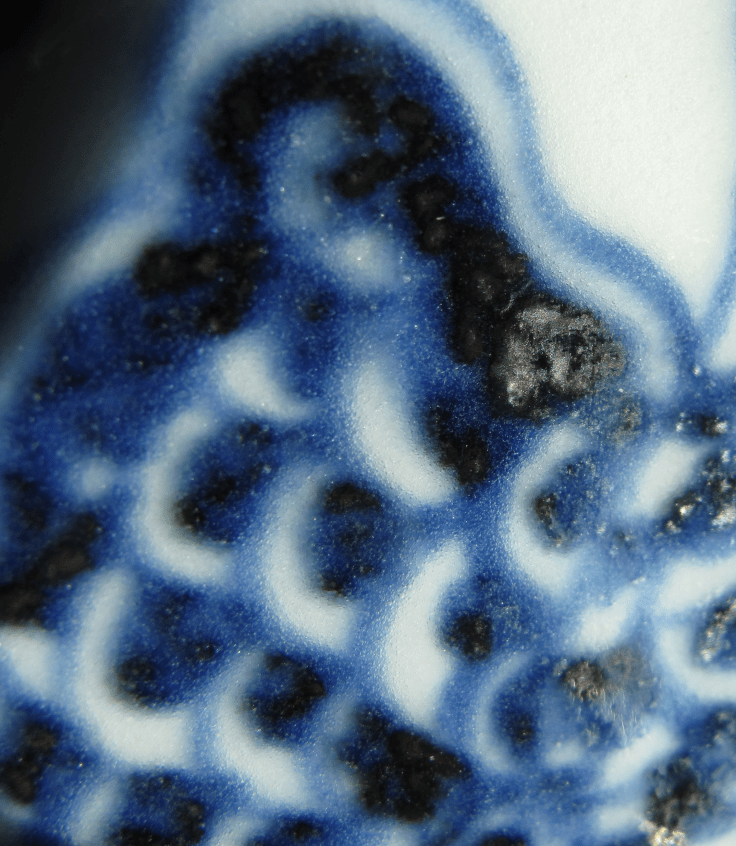

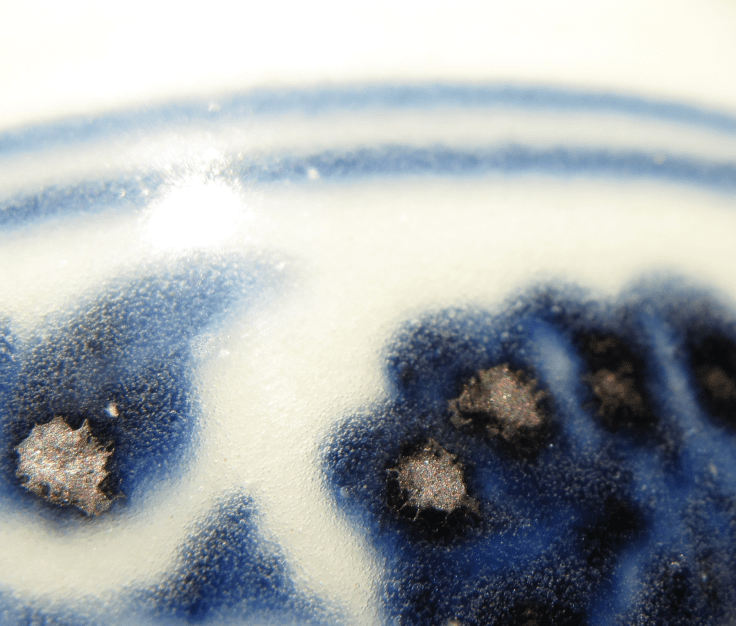

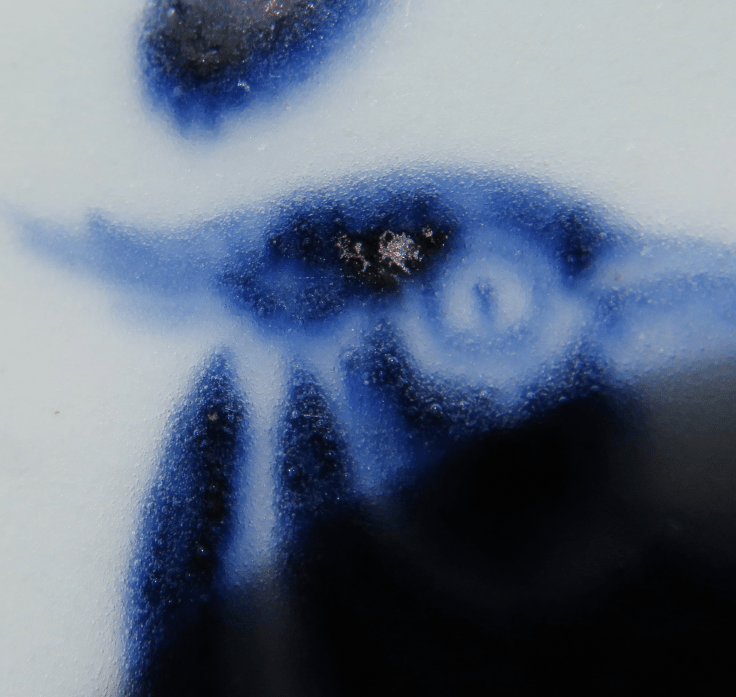

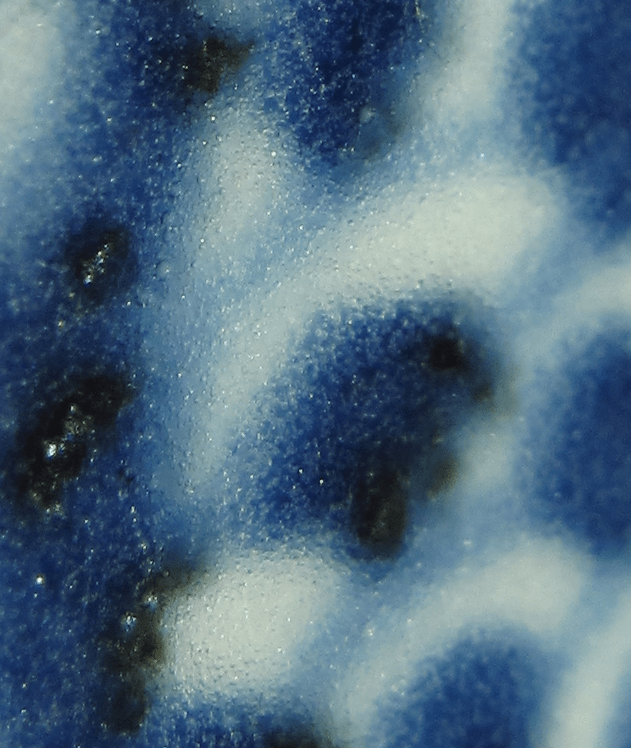

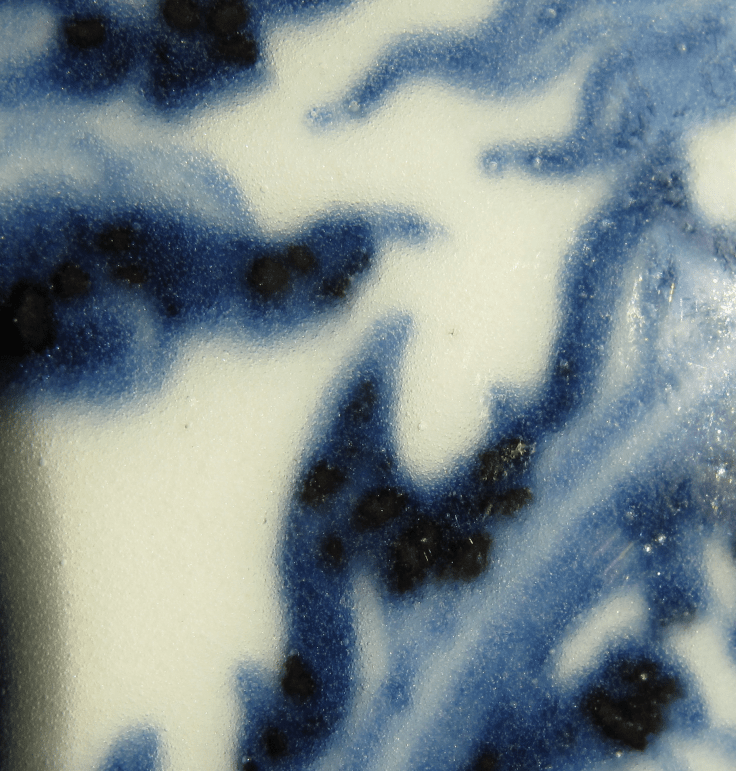

Look at Figures 9-12, from the neck, the plaques do show some light reflections. But these are poor light reflections that are not at all colorful. It only shows the low metallic component of these plaques. Still, it is worth your effort to look at them carefully, and know the texture of them. You should also note that they are rather thinner than Yuan plaques.

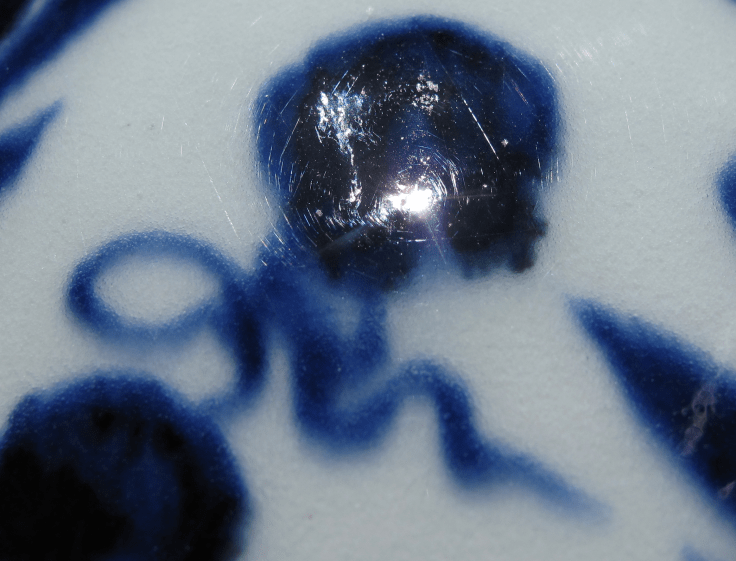

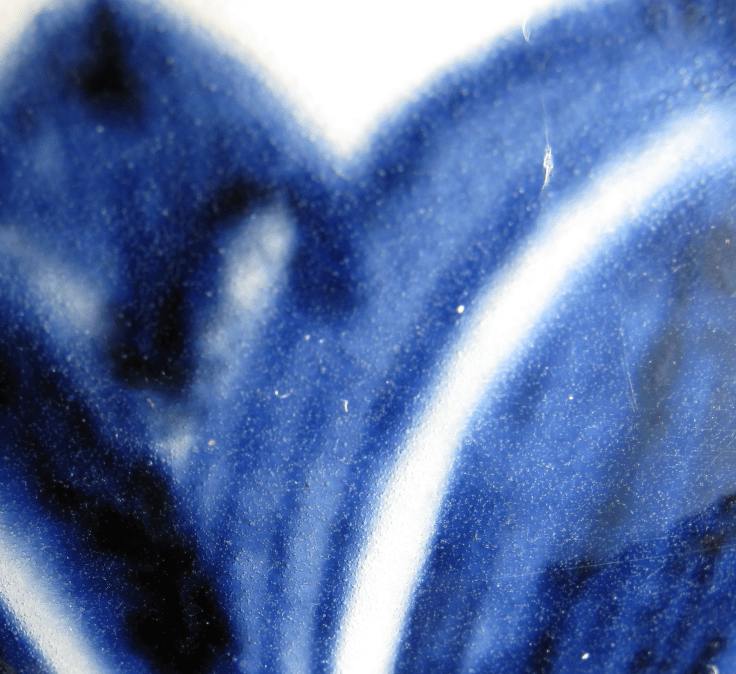

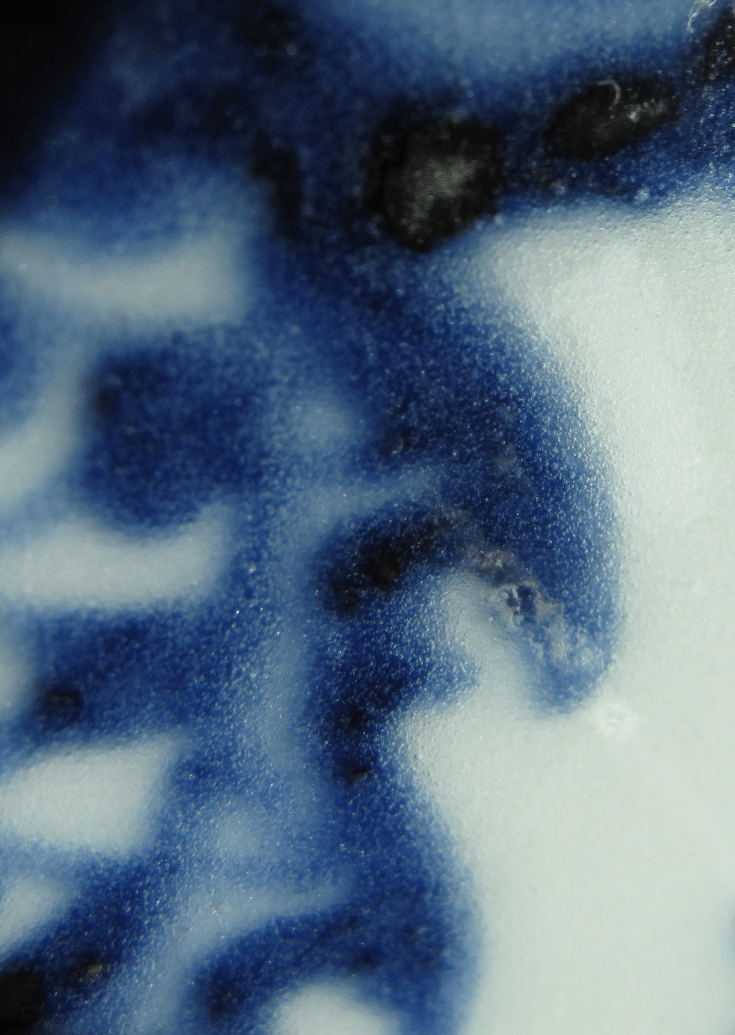

Now, the plaques of the body is quite different (Figures 13-17). Its reflections are quite colorful, though when compared to the Yuan and Yongle B & Ws, the reflection is not as strong and not as multi-color. Still, it is much more colorful than those in the neck. Even for the flares and drippings, they follow the pattern of the two previous periods. On that standard alone, we can tell that this is a genuine Xuande. But from these photos, if we care to look at the bubbles, they serve as further evidence that it is without doubt a Xuande.

Look at Figure 15, just above the colorful plaque, the lacunae are beautiful. Above that, the large bubbles are just right, so are the small bubbles. And look at the large bubbles again, and in other photos, there are so many that show the classic semi-opaque appearance. That is all that you need to know that the dye pigment is Sumali Blue dye. But what about the bubbles in the neck part, from a dye that is of a lower quality, you may want to ask. It is true that those bubbles are different from those in the body. But look at Figure 10, though the small bubbles are a lot fewer and do not show lacunae formation, the large bubbles are consistent with Sumali Blue dye. They might be just a bit smaller than those in the body, but, in conformity with the Sumali Blue dye, they all sit within a small patch of blue, and many are semi-opaque in appearance. I would say that, by just looking at the dye of the neck, one is still able to say that the dye is Sumali Blue dye.

I will now show you a few more photos with all the features that we have just talked about, so that you can acquaint yourself more with these feature (Figures 18-25).

Figure 18

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 22

Figure 23

Figure 23

Figure 24

Figure 24

Figure 25

Figure 25

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2  Figure 3

Figure 3  Figure 4

Figure 4  Figure 5

Figure 5  Figure 6

Figure 6  Figure 7

Figure 7  Figure 8

Figure 8  Figure 9

Figure 9  Figure 10

Figure 10  Figure 11

Figure 11  Figure 12

Figure 12  Figure 13

Figure 13  Figure 14

Figure 14  Figure 15

Figure 15  Figure 16

Figure 16  Figure 17

Figure 17  Figure 18

Figure 18  Figure 19

Figure 19  Figure 20

Figure 20  Figure 21

Figure 21  Figure 22

Figure 22  Figure 23

Figure 23

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 5 Figure 6

Figure 6 Figure 7

Figure 7 Figure 8

Figure 8 Figure 9

Figure 9 Figure 10

Figure 10 Figure 11

Figure 11 Figure 12

Figure 12 Figure 13

Figure 13 Figure 14

Figure 14 Figure 15

Figure 15 Figure 16

Figure 16 Figure 17

Figure 17 Figure 18

Figure 18 Figure 19

Figure 19 Figure 20

Figure 20 Figure 21

Figure 21 Figure 22

Figure 22 Figure 23

Figure 23 Figure 24

Figure 24 Figure 25

Figure 25

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 5 Figure 6

Figure 6 Figure 8

Figure 8 Figure 9

Figure 9 Figure 10

Figure 10 Figure 11

Figure 11 Figure 12

Figure 12 Figure 13

Figure 13 Figure 14

Figure 14 Figure 15

Figure 15 Figure 16

Figure 16 Figure 17

Figure 17 Figure 18

Figure 18 Figure 19

Figure 19 Figure 20

Figure 20 Figure 21

Figure 21 Figure 22

Figure 22 Figure 23

Figure 23

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 5 Figure 6

Figure 6 Figure 7

Figure 7 Figure 8

Figure 8 Figure 9

Figure 9 Figure 10

Figure 10 Figure 11

Figure 11 Figure 12

Figure 12 Figure 13

Figure 13 Figure 14

Figure 14 Figure 15

Figure 15 Figure 16

Figure 16 Figure 17

Figure 17 Figure 18

Figure 18 Figure 19

Figure 19 Figure 20

Figure 20 Figure 21

Figure 21 Figure 22

Figure 22

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 5 Figure 6

Figure 6 Figure 7

Figure 7 Figure 8

Figure 8 Figure 9

Figure 9 Figure 10

Figure 10 Figure 11

Figure 11 Figure 12

Figure 12 Figure 13

Figure 13 Figure 14

Figure 14 Figure 15

Figure 15 Figure 16

Figure 16 Figure 17

Figure 17 Figure 18

Figure 18 Figure 19

Figure 19 Figure 20

Figure 20 Figure 21

Figure 21 Figure 22

Figure 22 Figure 23

Figure 23 Figure 24

Figure 24 Figure 25

Figure 25