We all know that potters in the early Ming days are very skillful artists, as shown by the works that we still have today. They are not only skillful, they are creative. Many a time, they have created wares with such ingenuity that we can only marvel at the beauty of their work. Unfortunately, many of these beautiful wares were destroyed when war and political upheavals swept through the country all these centuries. Still a few remains. Of those that remain, some are rare, some are very rare, and some are extremely rare. In terms of monetary value, the rarer the ware is, the more expensive it would be. But there is a catch here—the rarer the ware is, the chances for it to be refuted by collectors and museum curators and experts become much higher. This is a time when we need to be very careful in our judgment. Many people pay a lot of attention to provenances, and I am not going to dispute that. But to me, the most important way to evaluate a ware is to go by its characteristics. This is particularly true when we are dealing with Blue and White of the early Ming period. We all know potters in those periods use the Sumali Blue dye for the painting of the motif. As I have shown you in the previous articles, we now know very well the characteristics of the Sumali Blue dye. So, in dealing with a rare ware in those periods, all that we need to do is to examine the characteristics of the dye, and see if they match those of Sumali Blue dye. It they match, I do not see any problem in confirming or denying the ware.

I’ll now show you a rather rare Blue and White of the Xuande period. It is a ware in the shape of a Pipa which is a Chinese musical instrument very similar to a lute in the west.

Figure 1

Figure 1

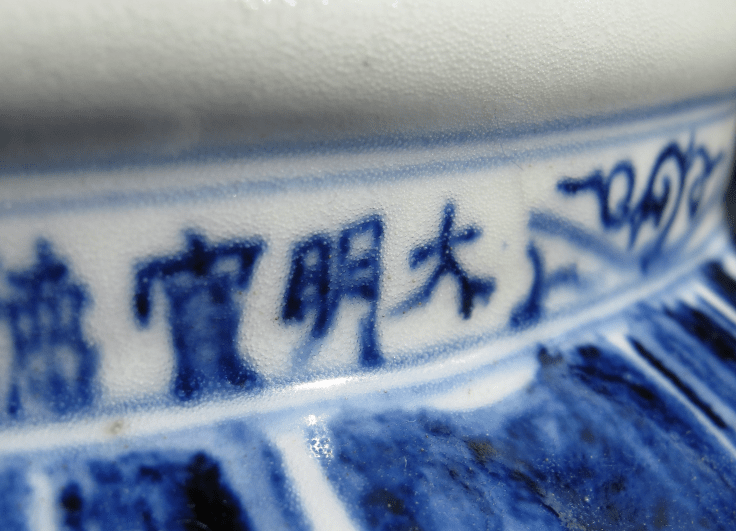

This Pipa measures 15 1/2 inches long, 6 1/4 inches wide and bulges up in the body for 3 1/2 inches, so that the body is almost a semi-spherical body. You can see that at the top of the Pipa, the part we call the scroll, is in the form of the head of a ram, completed with two curly horns and two ears sticking up high. A little below that is the tuning pegs. It is a very nicely made ware. What we now need to know is wether the ware belongs to the Xuande period, as the mark in the neck says (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Figure 2

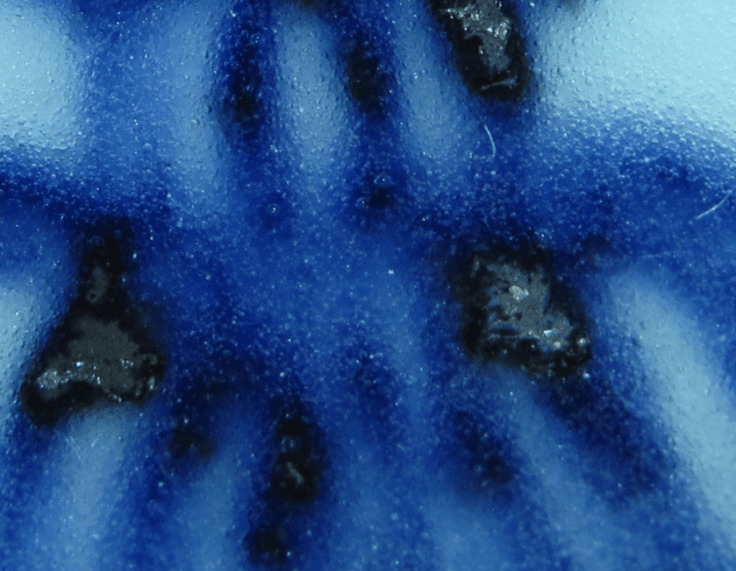

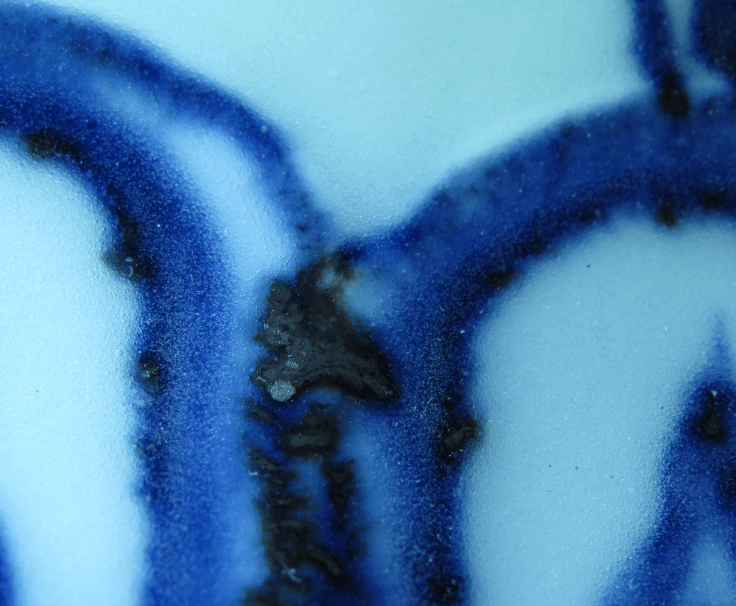

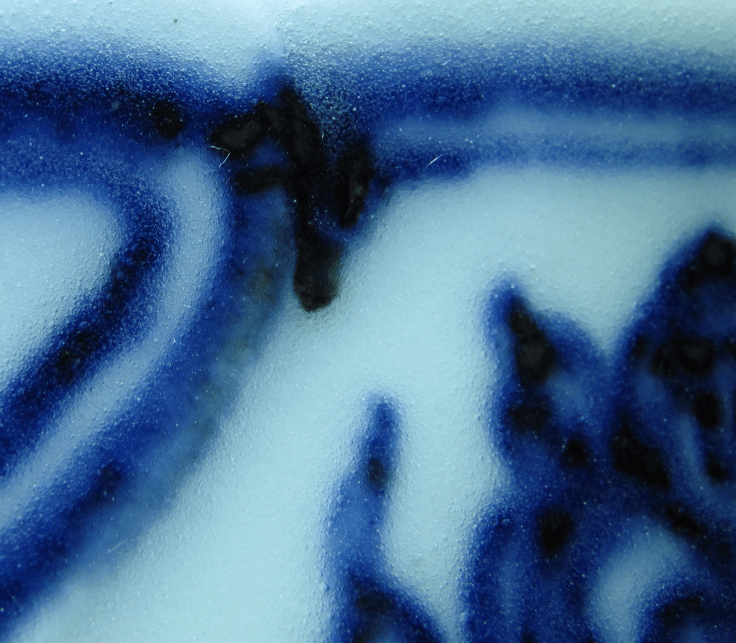

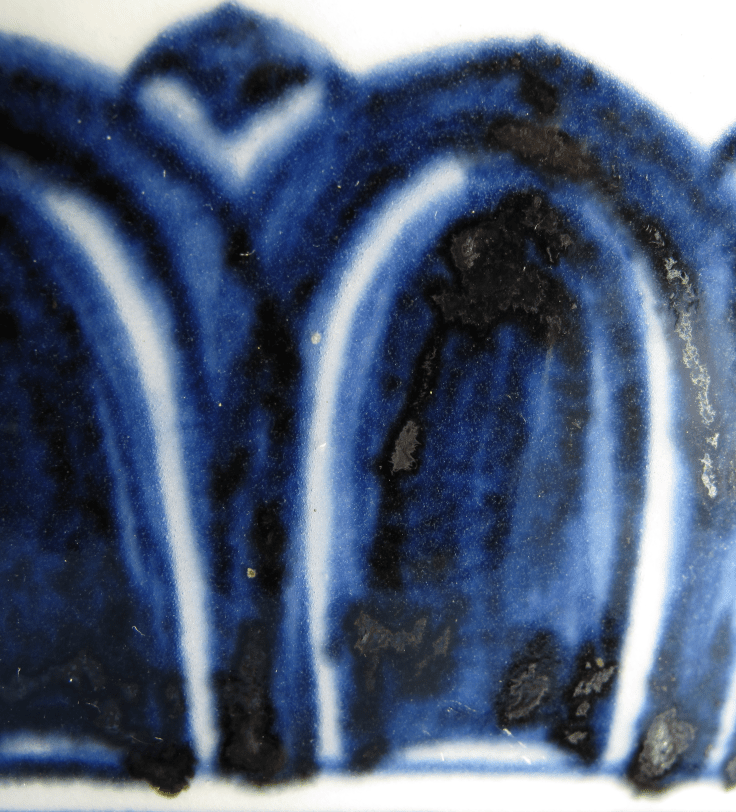

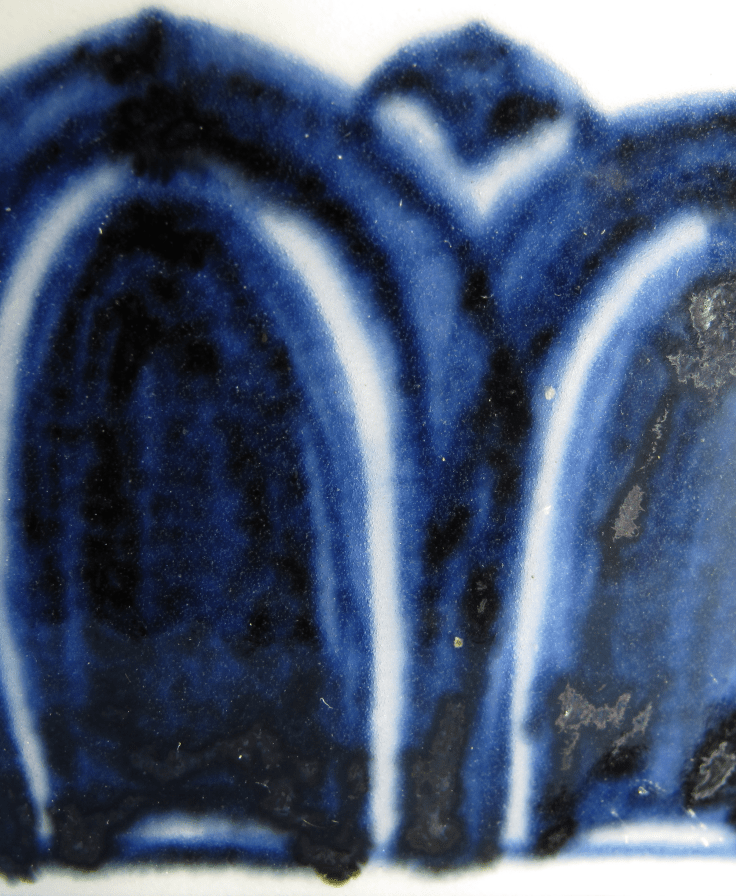

There is no secret here. We just look at the characteristics of the Somali Blue dye. The rarely seen shape of the ware should be your last worry. Let me show you a few photos of the plaques first.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 8

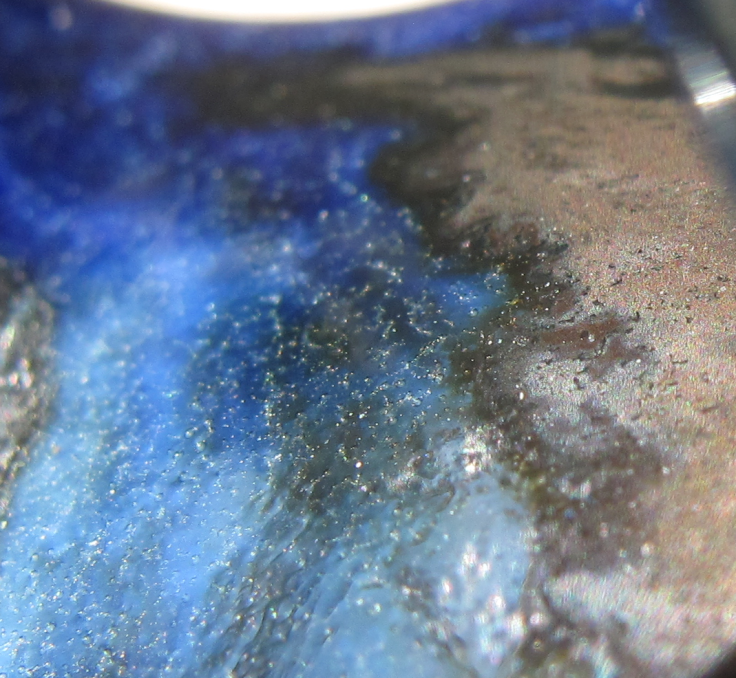

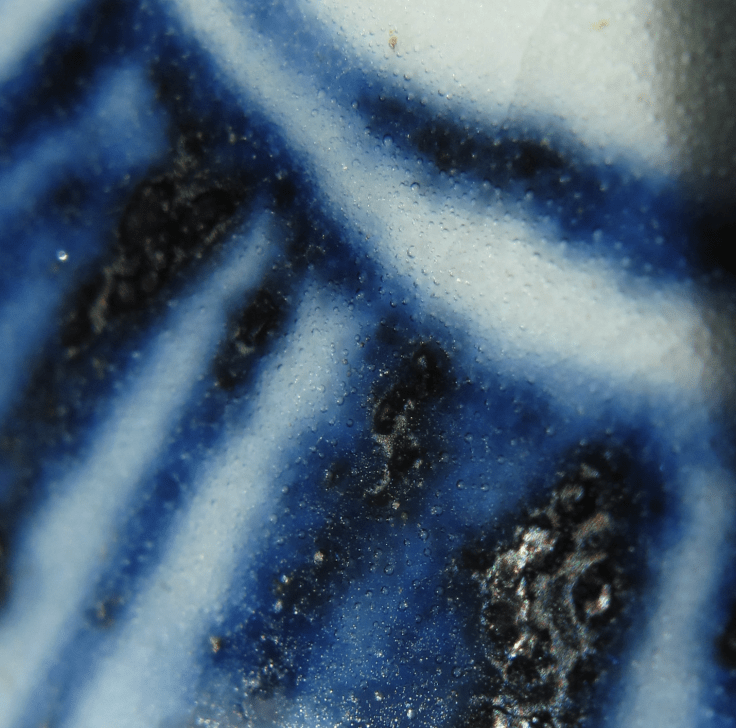

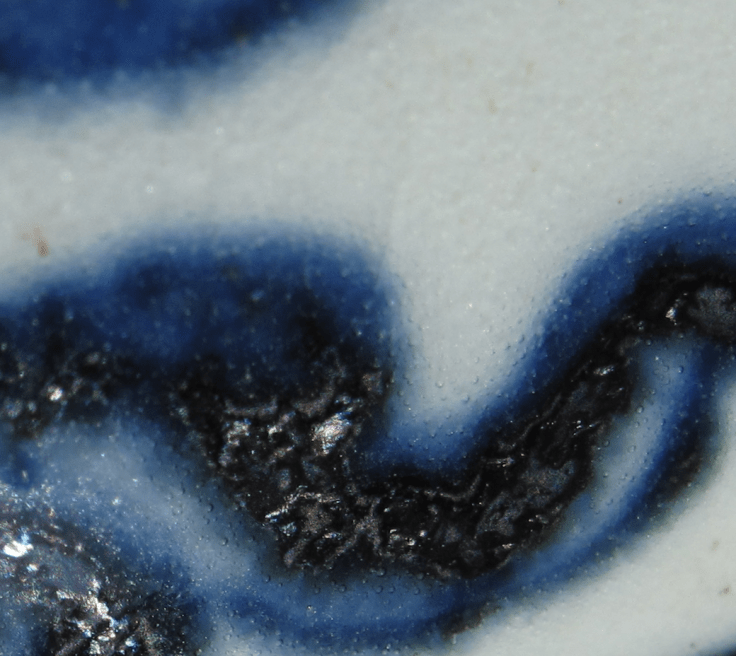

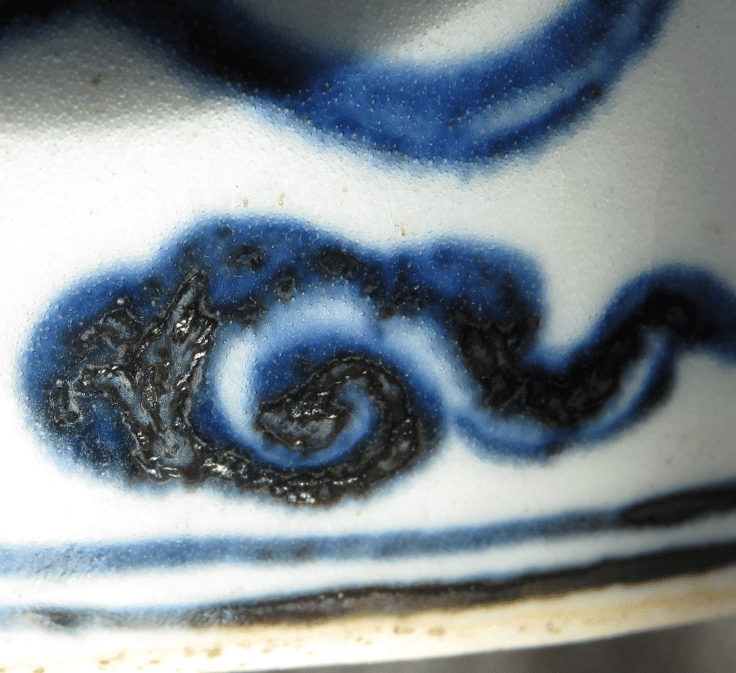

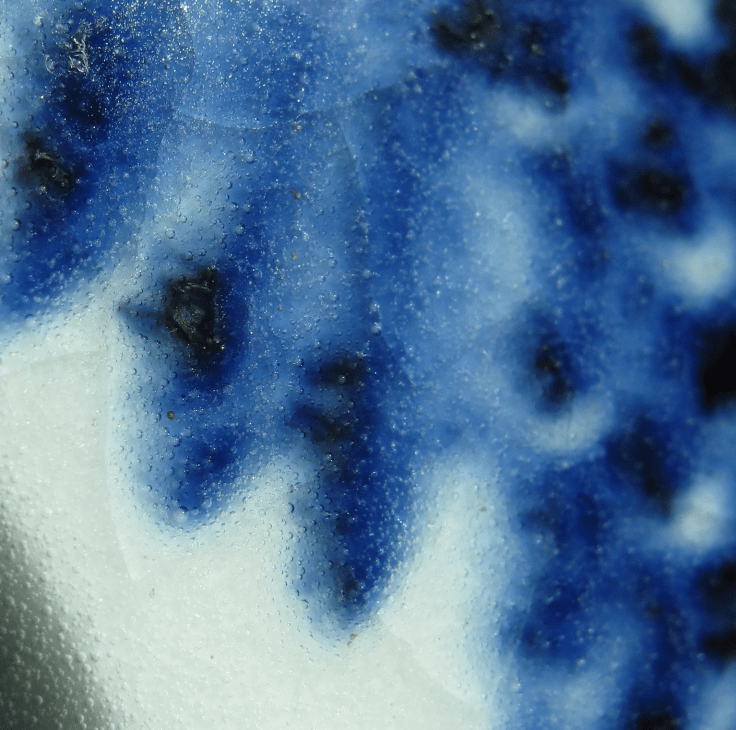

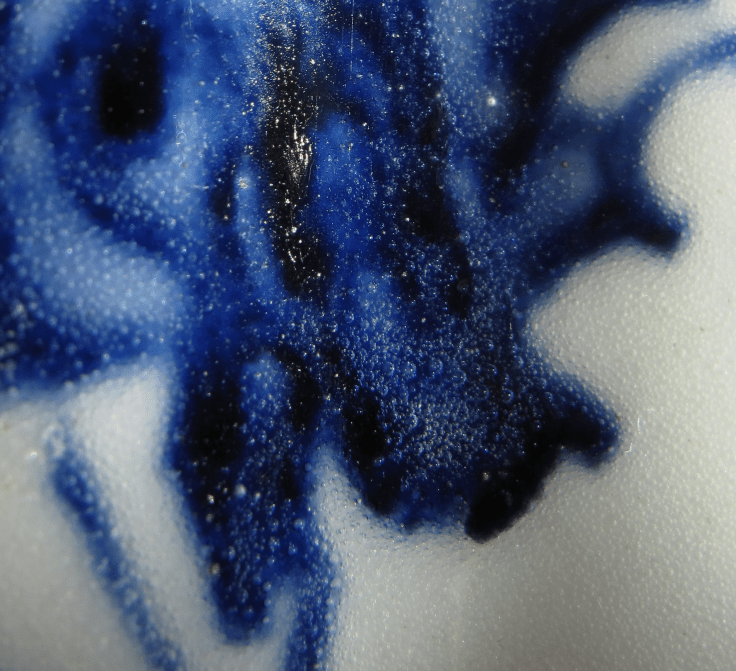

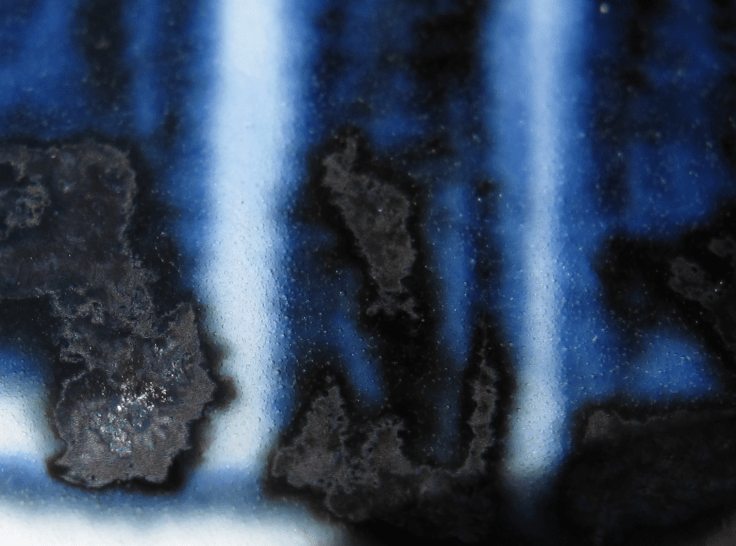

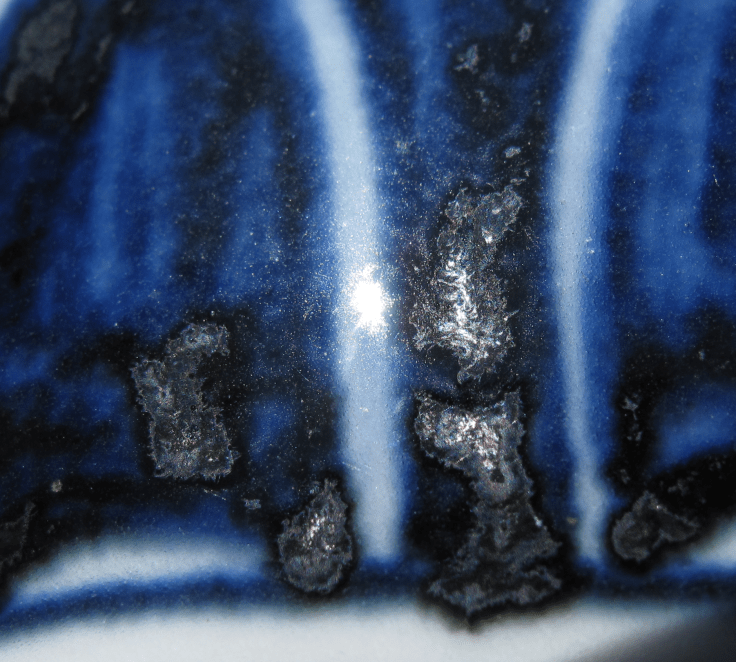

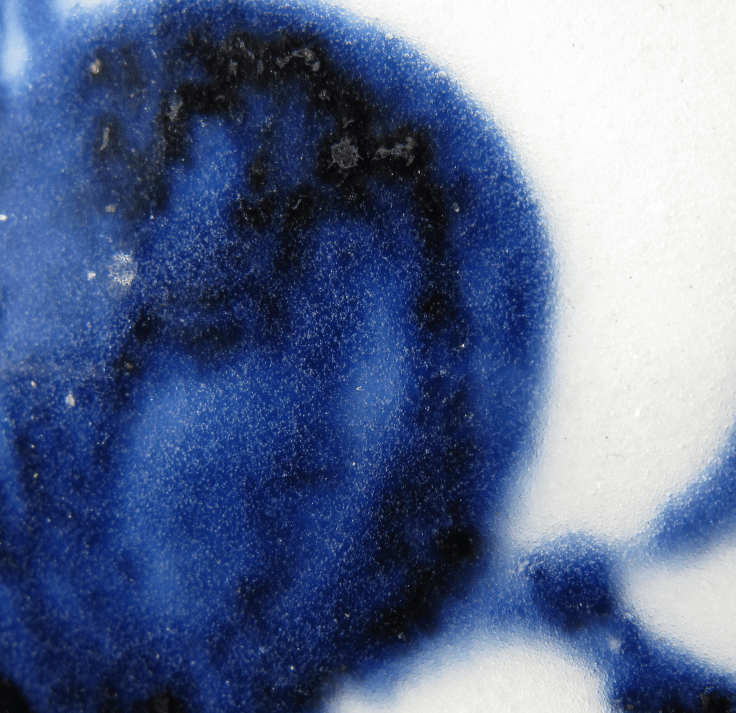

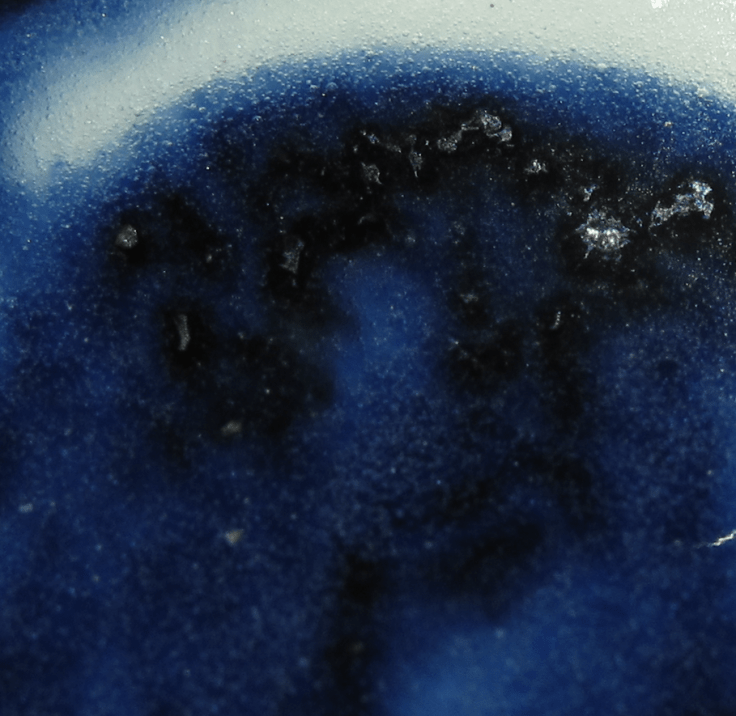

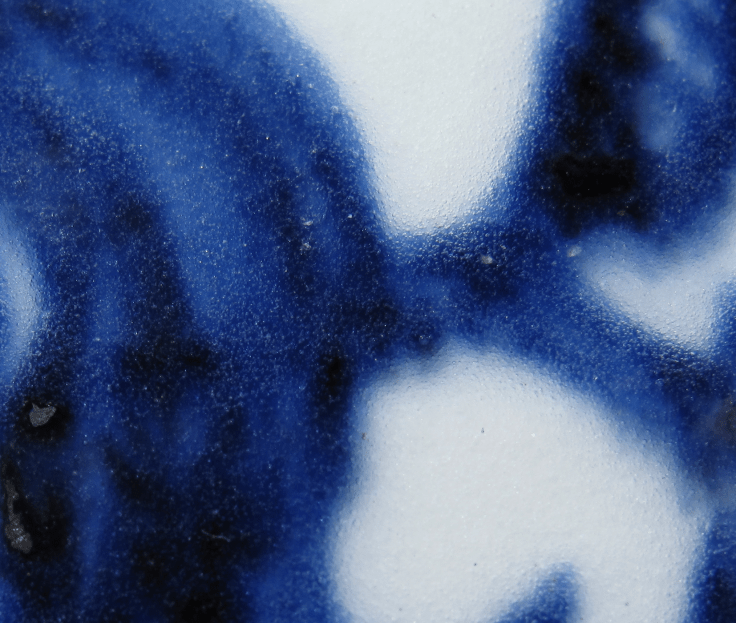

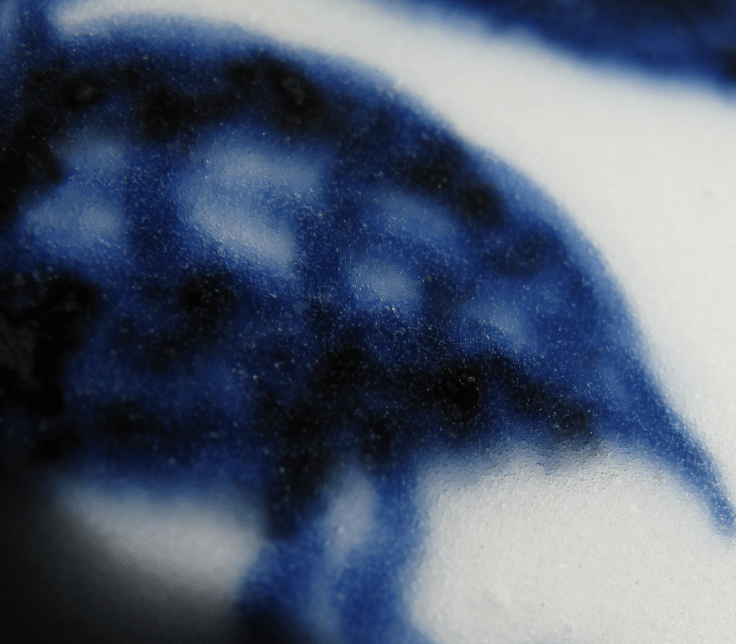

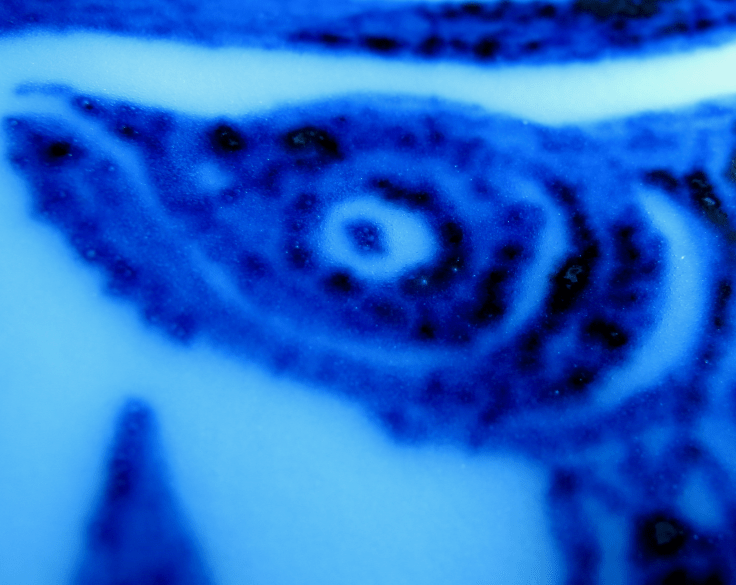

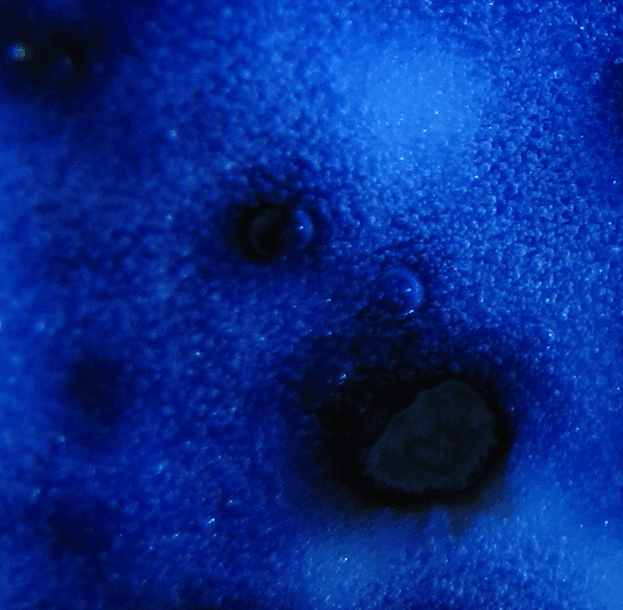

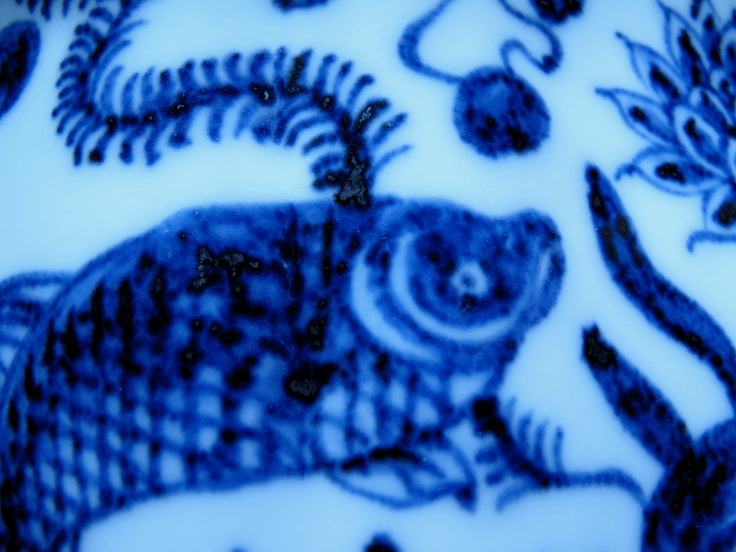

Figure 8 shows the head of the ram. The whole head is painted blue. You can see large patches of plaque here and there. They do not seem to have the metallic shiny foil floating on top, so that the plaques belong to those plaques that have a simpler structure, with only a muddy layer. In fact, the whole ware is painted with blue dye similar to the head here. A look at the blue patches anywhere in the pipa, there is little aluminum foil floating on top anywhere.

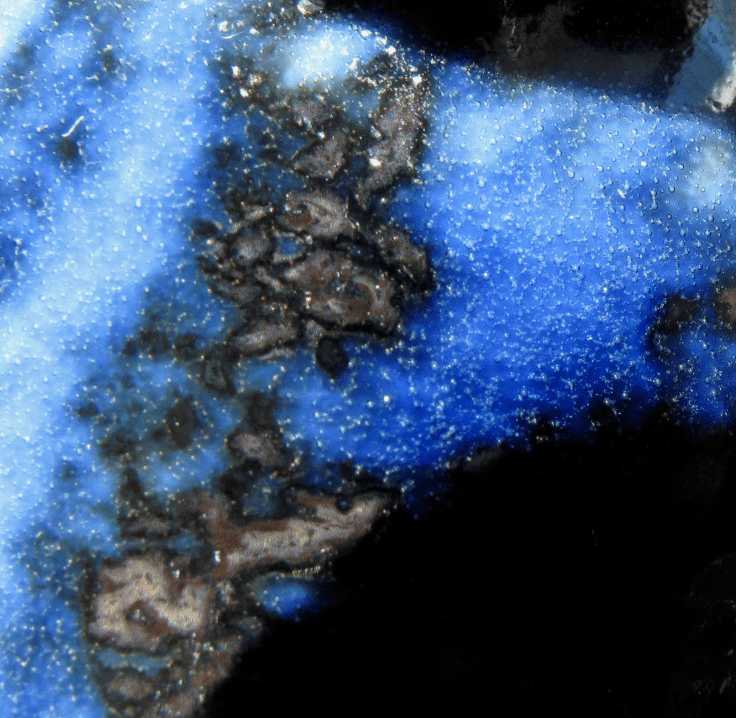

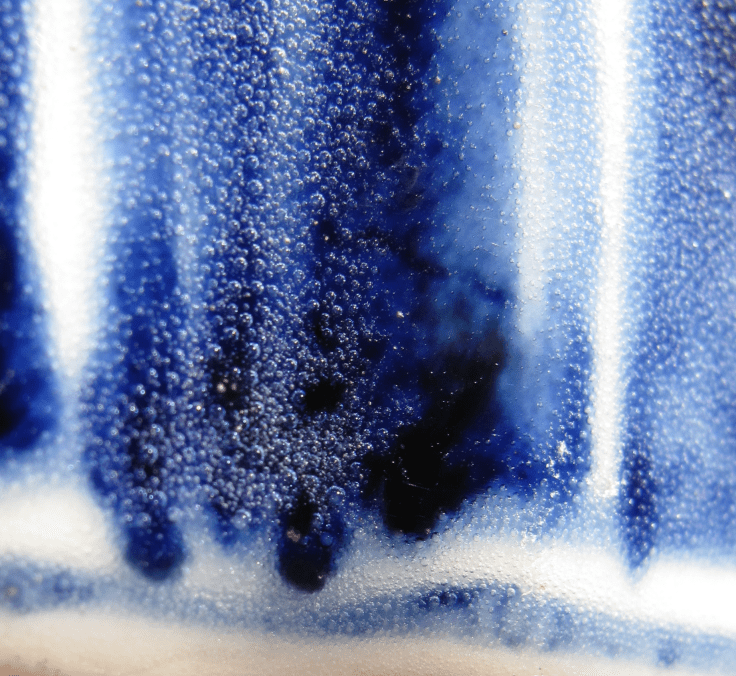

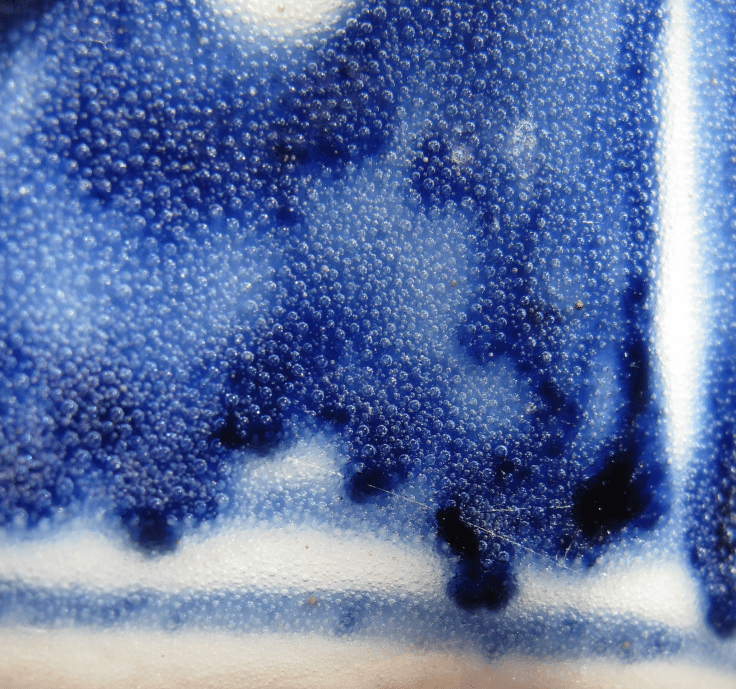

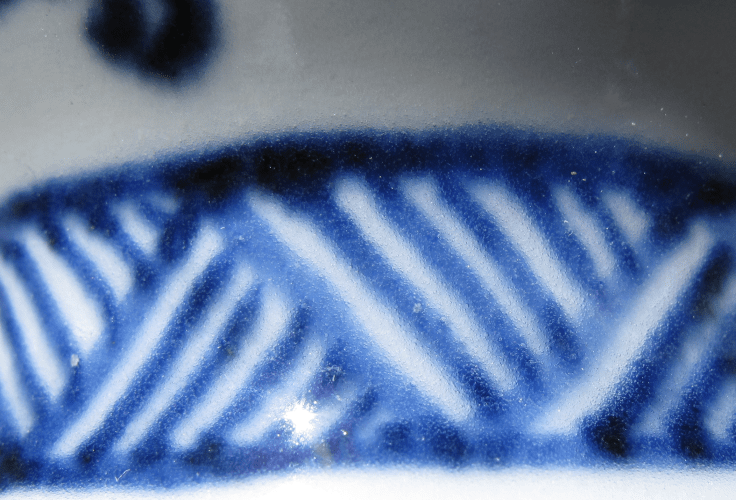

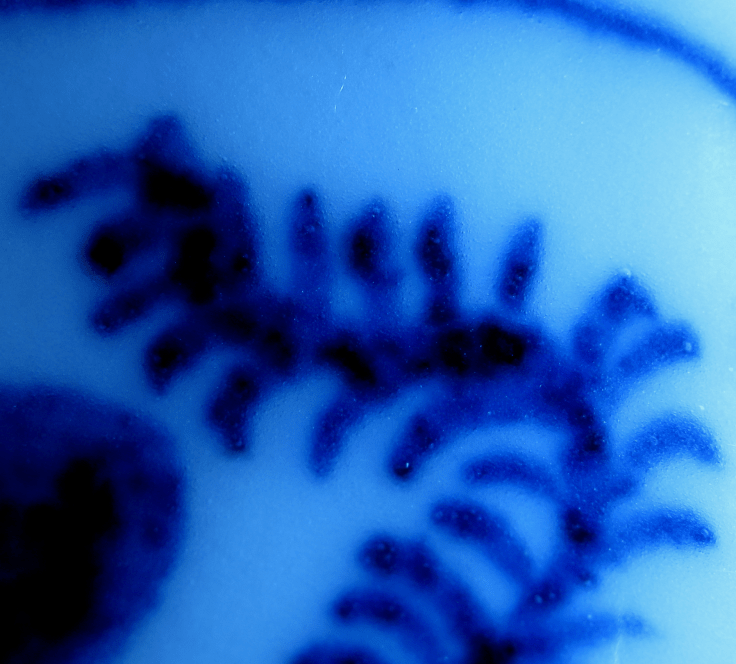

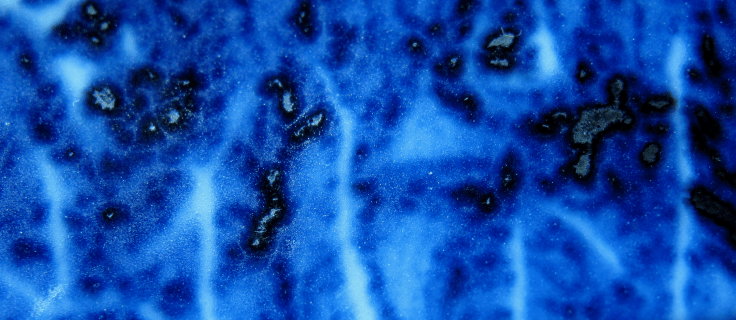

In Figure 3 and Figure 4, even when the plaques are quite large, you can only see the muddy layer. Under the sun, the plaques are not highly reflective, indicating that the metallic and other crystalline contents are low. But in other areas, (Figures 5-7), they have a different look. But no matter how you look at it, you have to say that they are beautiful.

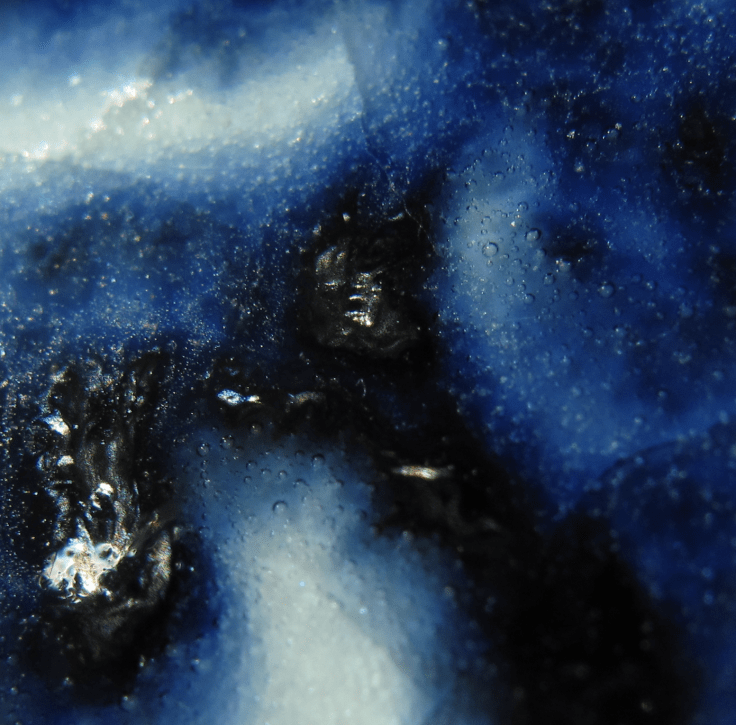

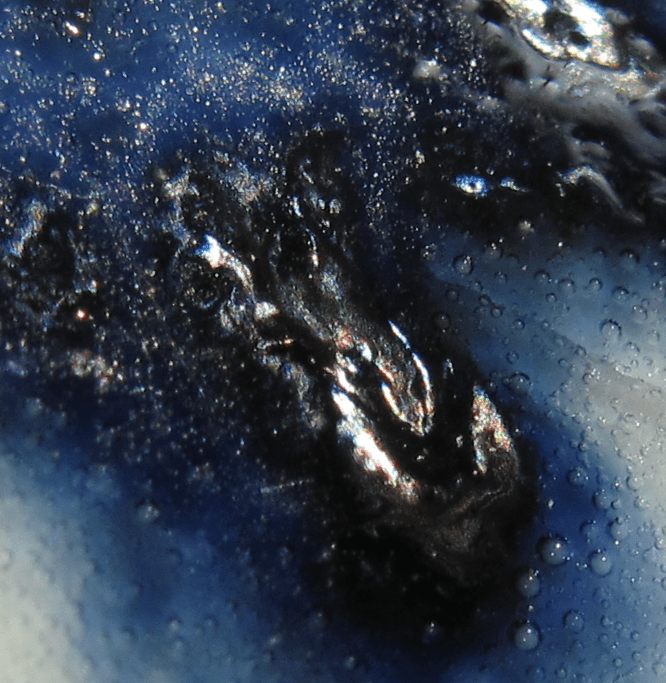

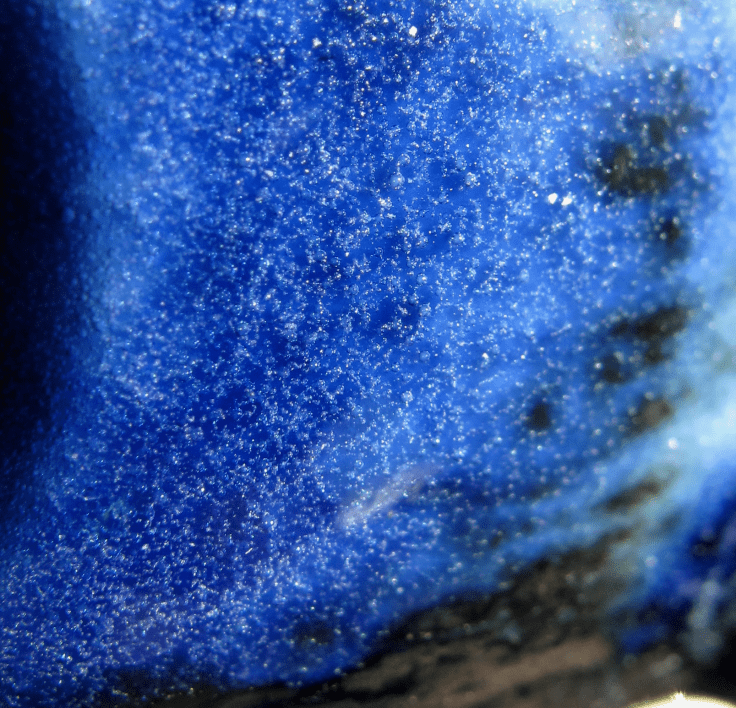

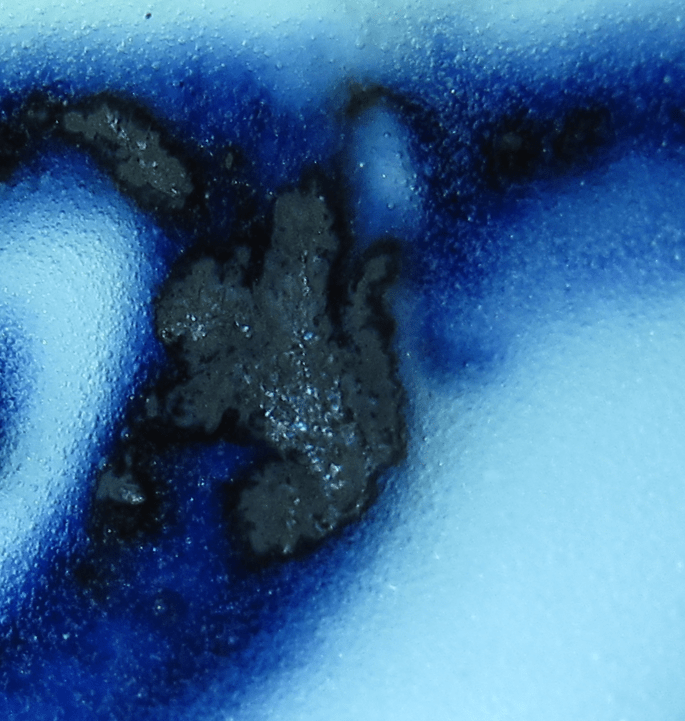

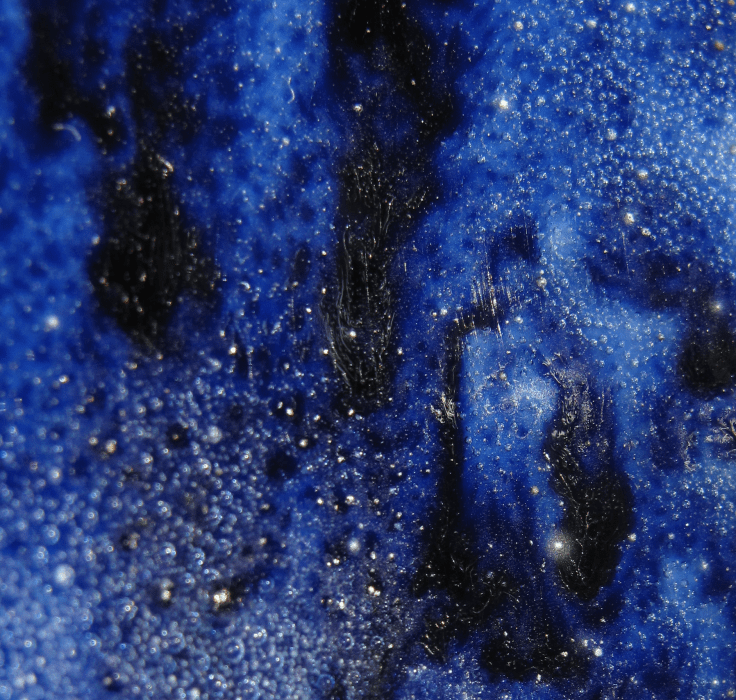

Now, let me show you areas where there are higher contents of metal and crystals, as indicated by the much more reflective nature of those areas.

Figure 9

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 14

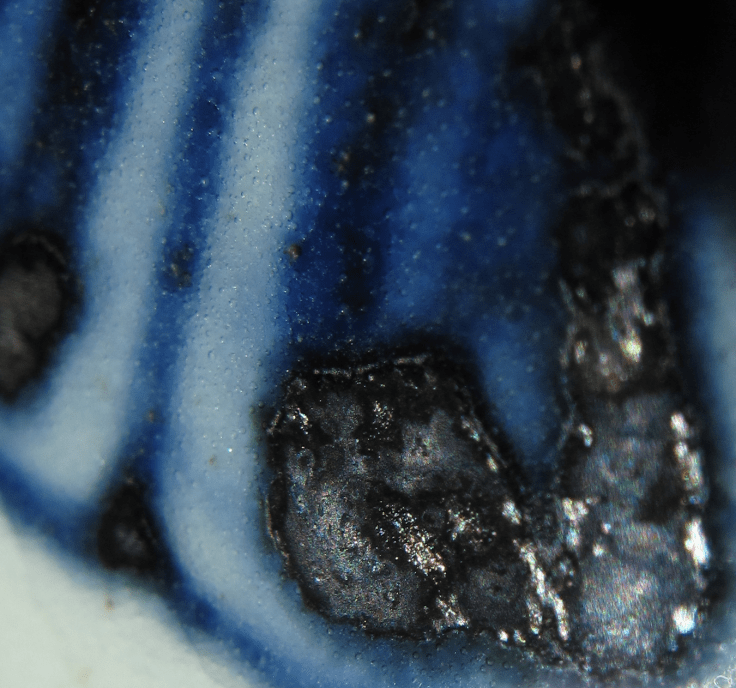

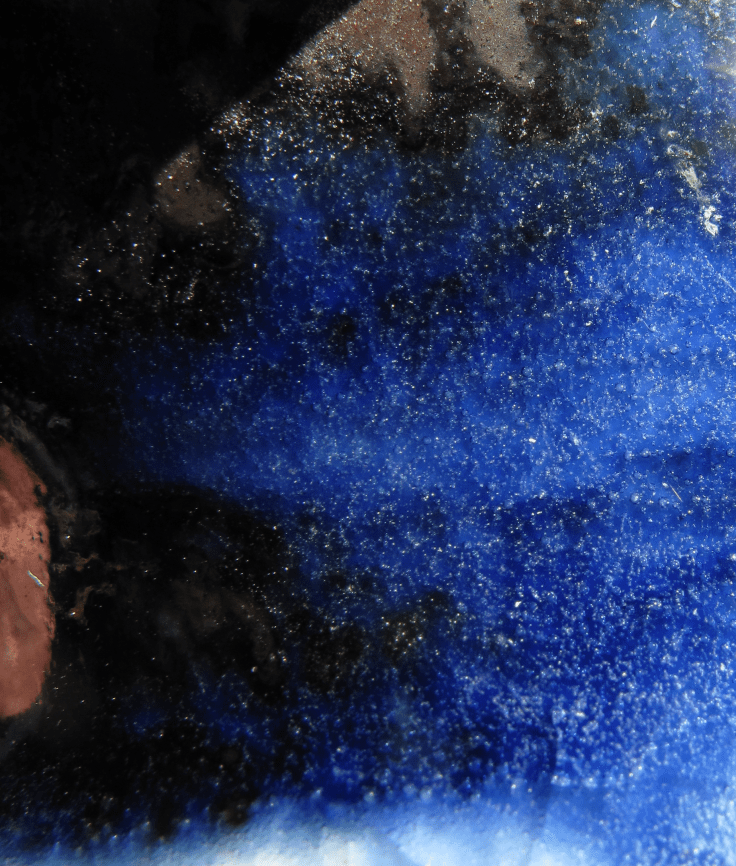

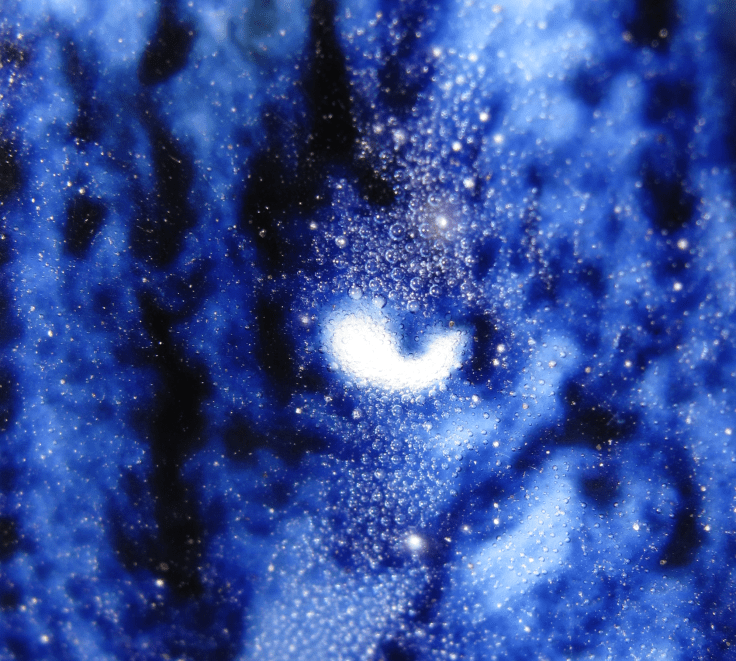

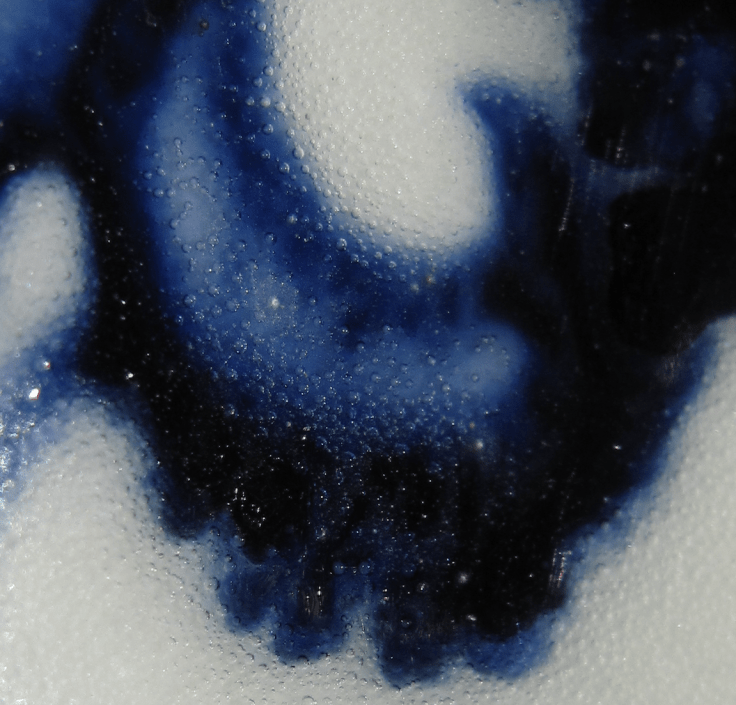

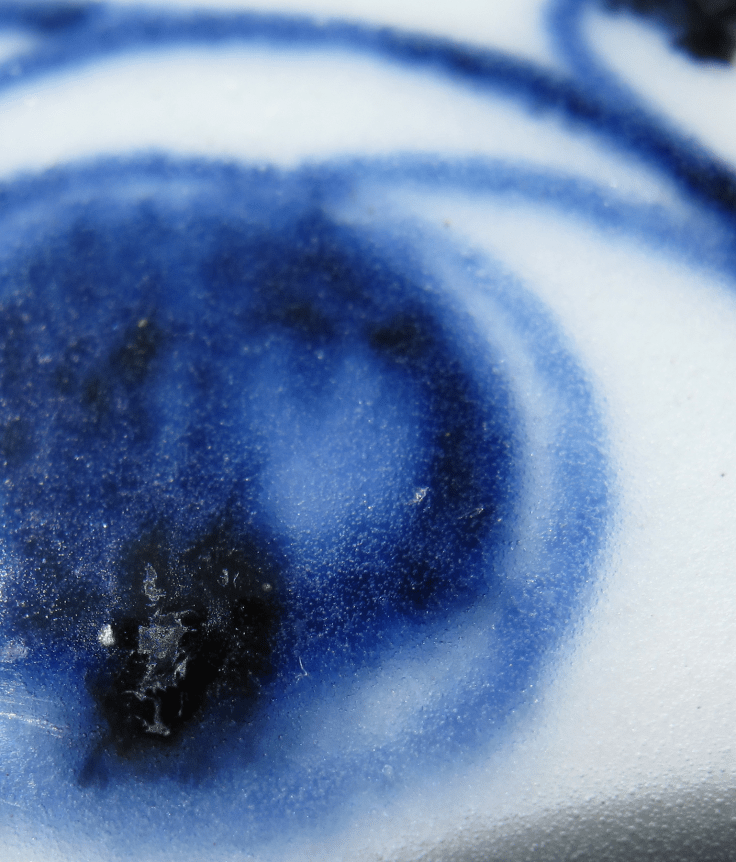

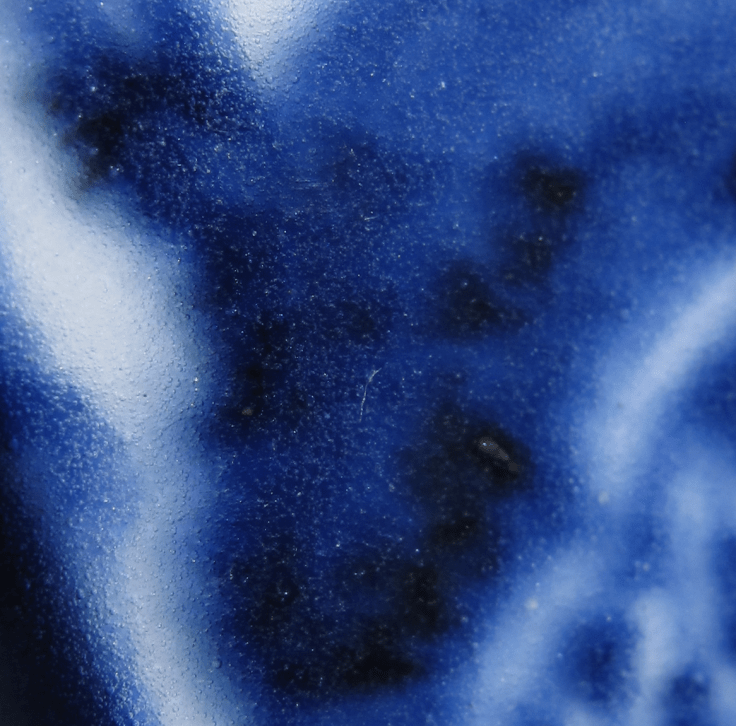

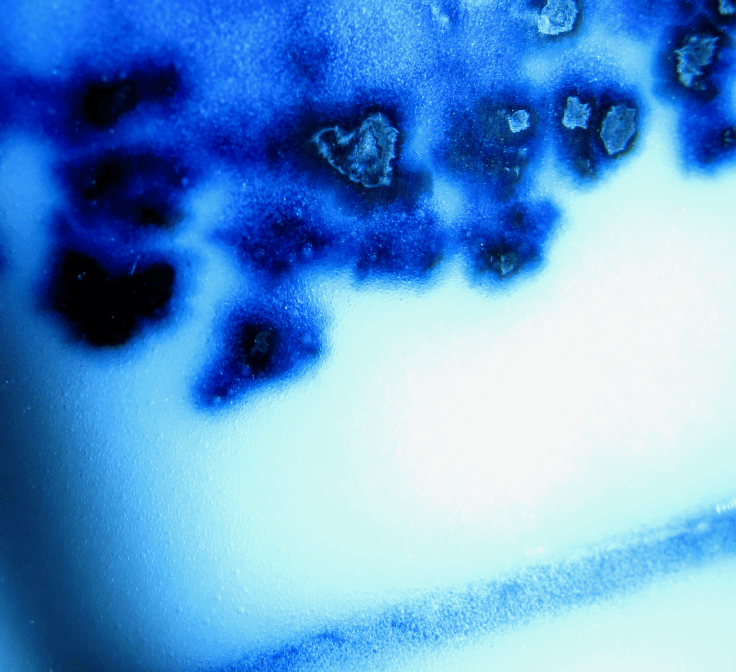

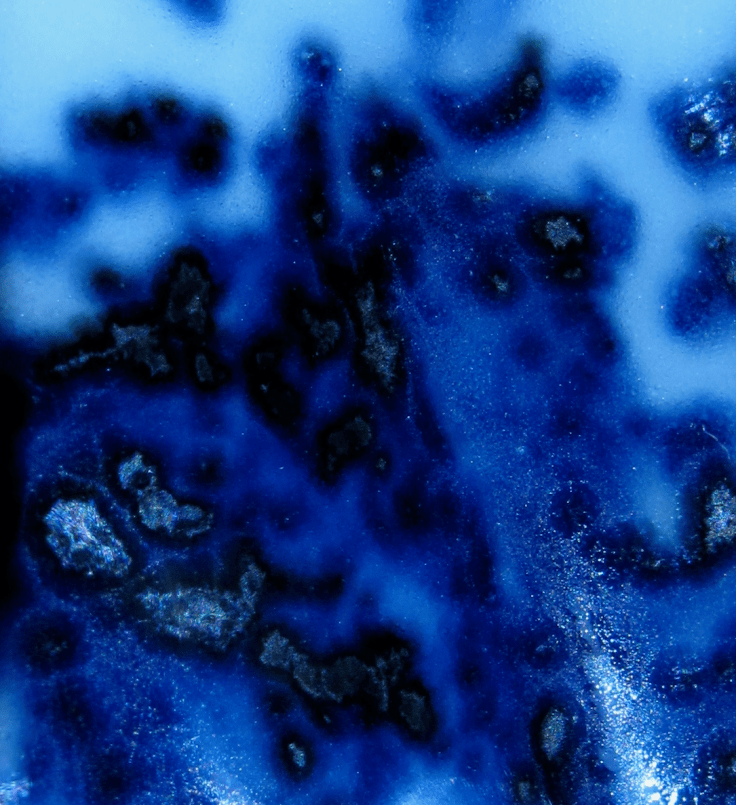

Look at these beautiful plaques in different forms and their reflections (Figures 9-14). They are comparable to those that I have shown you in other wares. In figures 13 and 14, the plaques that are next to the reflective ones look like pale brownish patches sitting in a dark blue area, beyond which is the not so dark blue coloration. This is typical of the Somali Blue dye, as the other features are. There is a reason for the plaques to look so different when they are less than 1 cm apart. The curvature of the body is so large that the angle of sunlight striking on the surface would vary much even within a short distance, and this difference means a lot when it comes to the reflection of light.

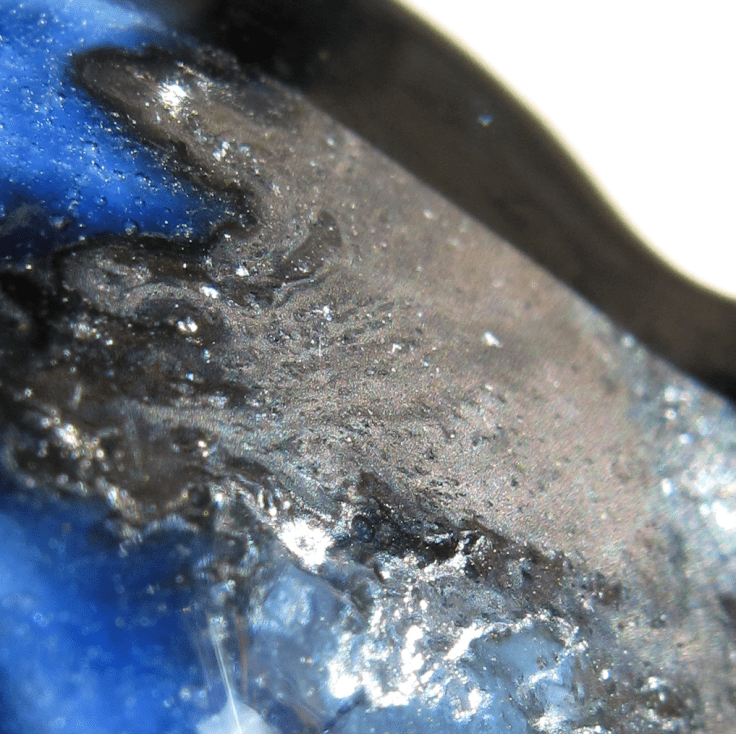

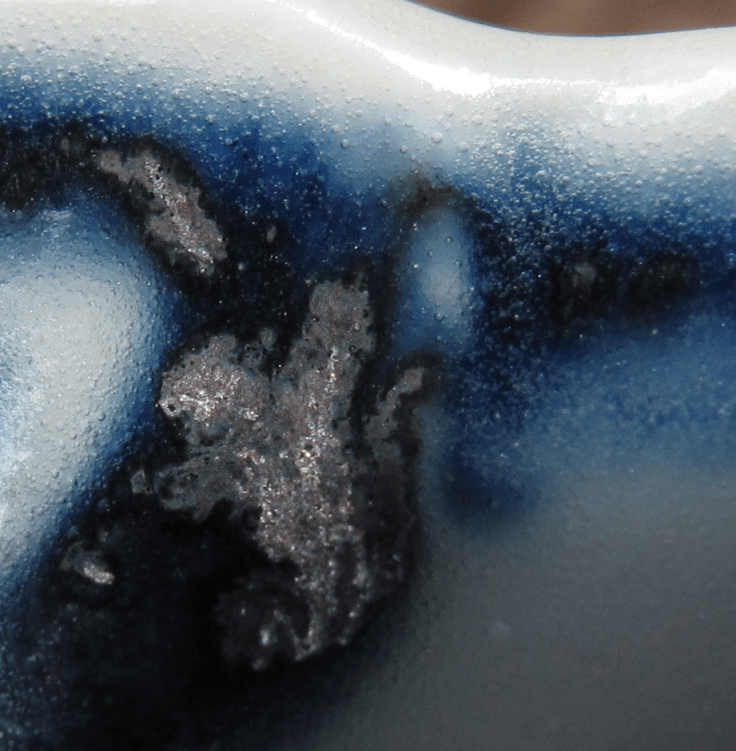

I’ll show you more photos of dull plaques morphing into brightly reflective ones with only a very short distance apart, maybe less than 1 cm.

Figure 15

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 19

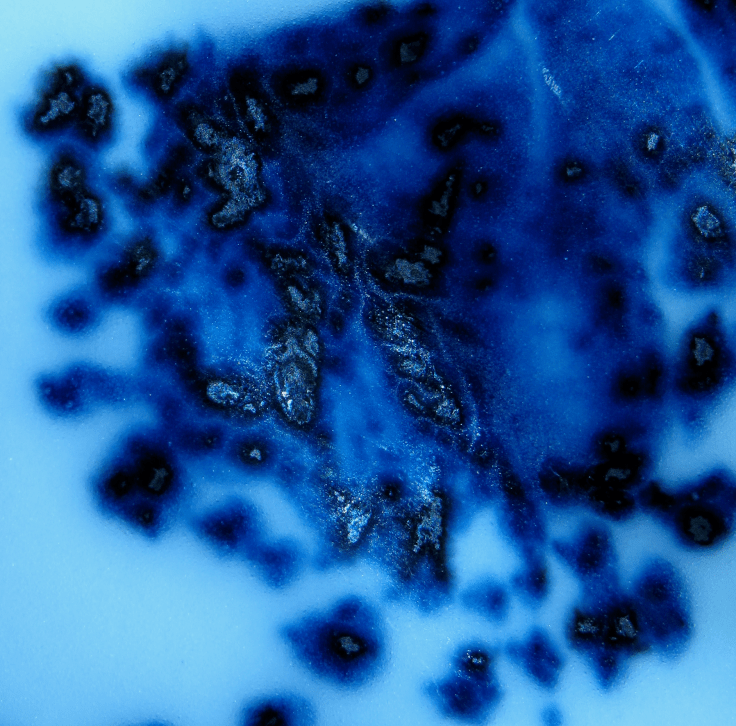

Look at Figures 15-19 carefully, and the dull plaques morphing into very colorful and reflective ones. Figures 18 and 19 are in fact taken from the same spot. But you’ll notice that a slight shift of the position of the ware, the reflections look quite different.

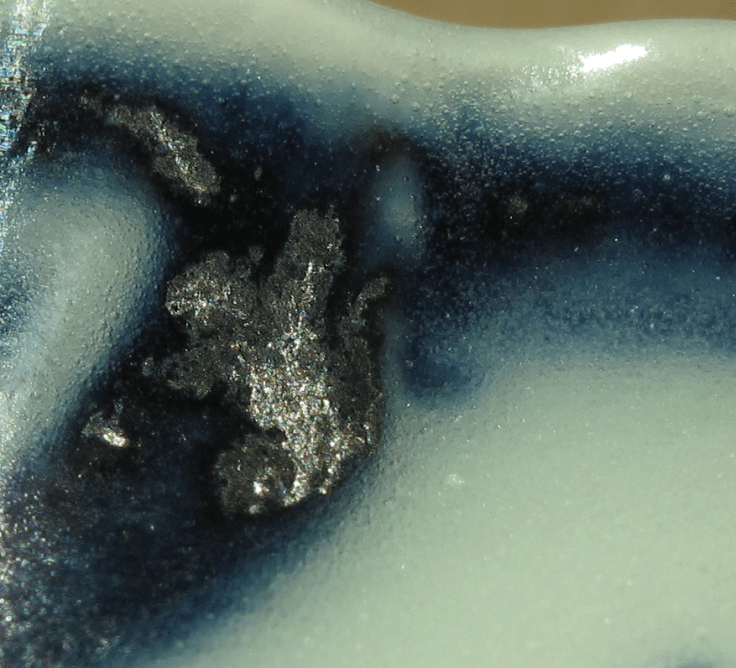

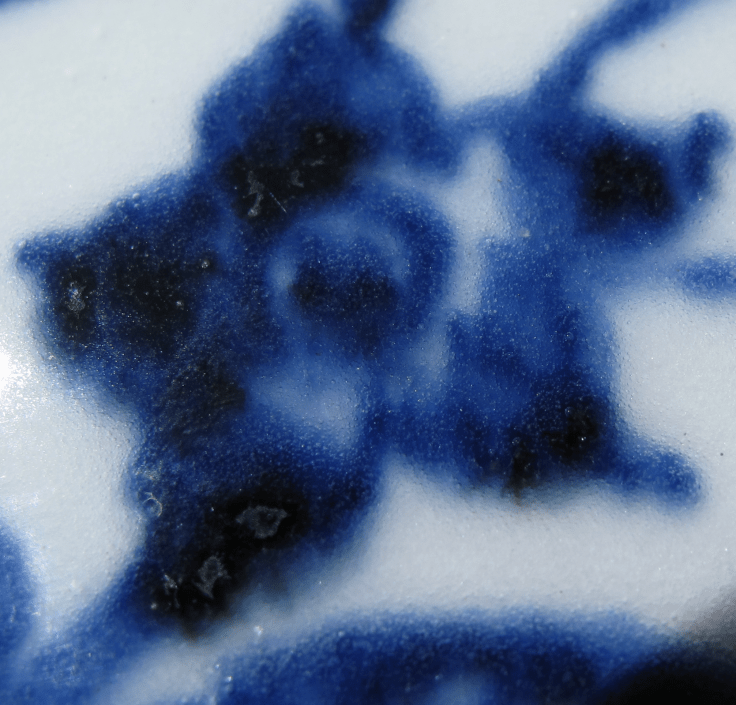

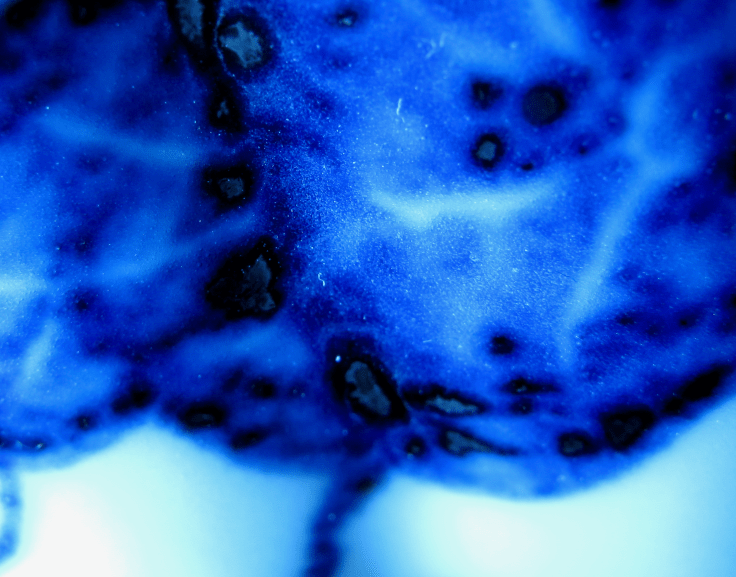

Now, I’ll show you an enlarged photo of one of the more colorful plaques (Figure 20). Do you notice the many tiny and yet very colorful particles around the main plaque? As I have explained before, these tiny particles are the components of a plaque before they aggregate and form a proper plaque.

Figure 20

Figure 20

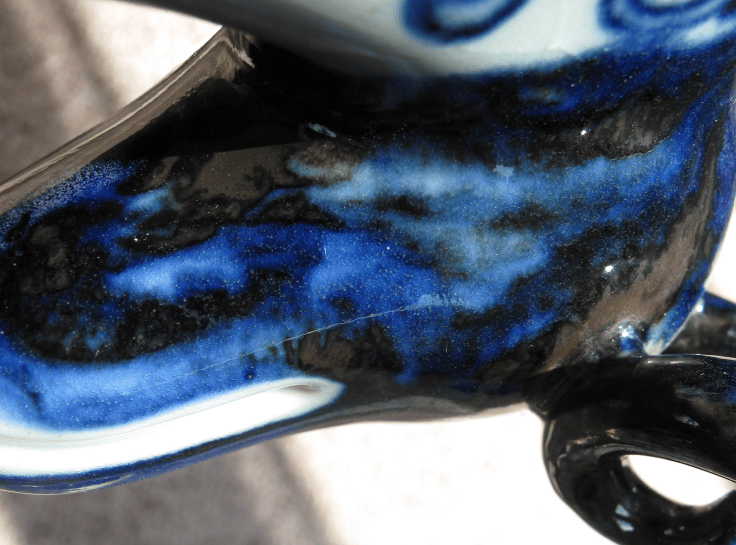

You may be interested to know how these plaques look like when the photos are taken in a not-too-close-up range.

Figure 21

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 22

Figure 23

Figure 23

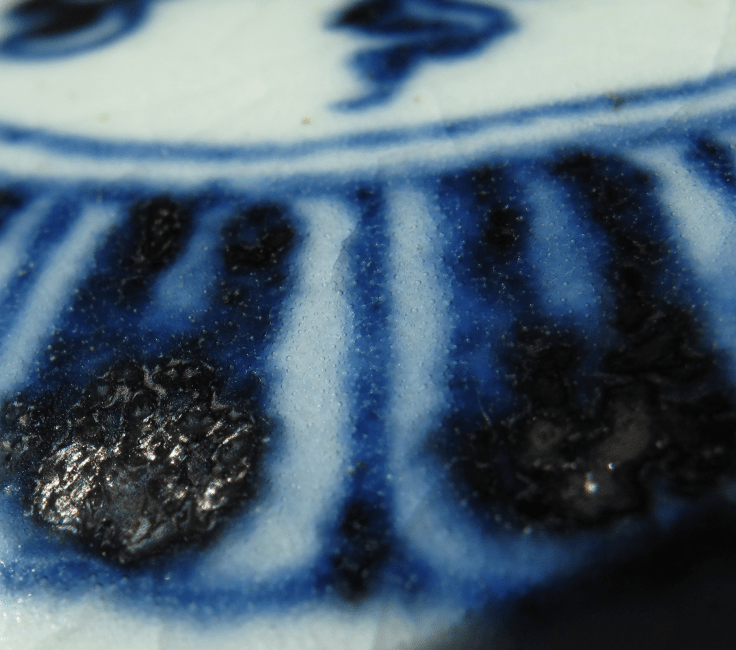

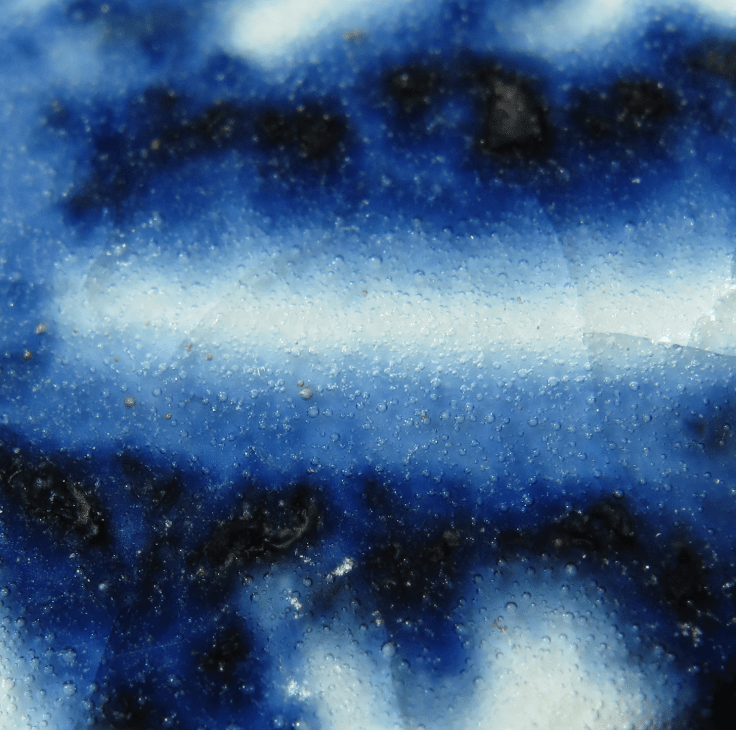

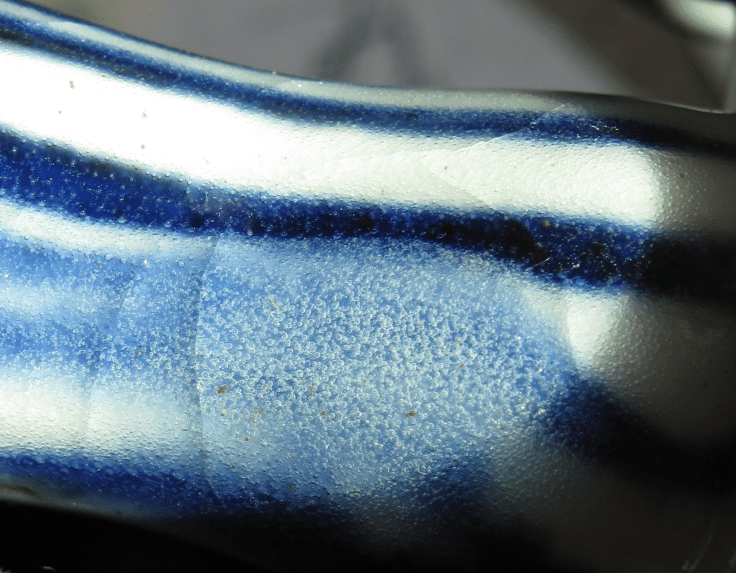

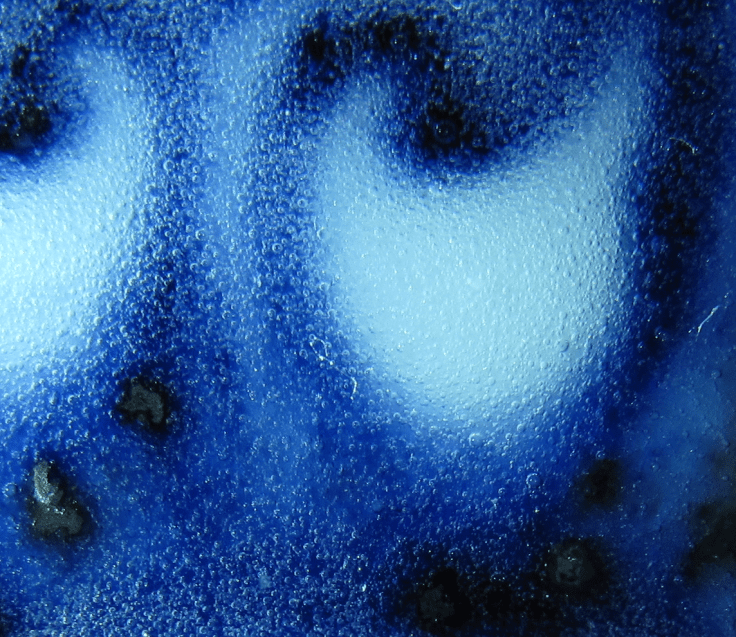

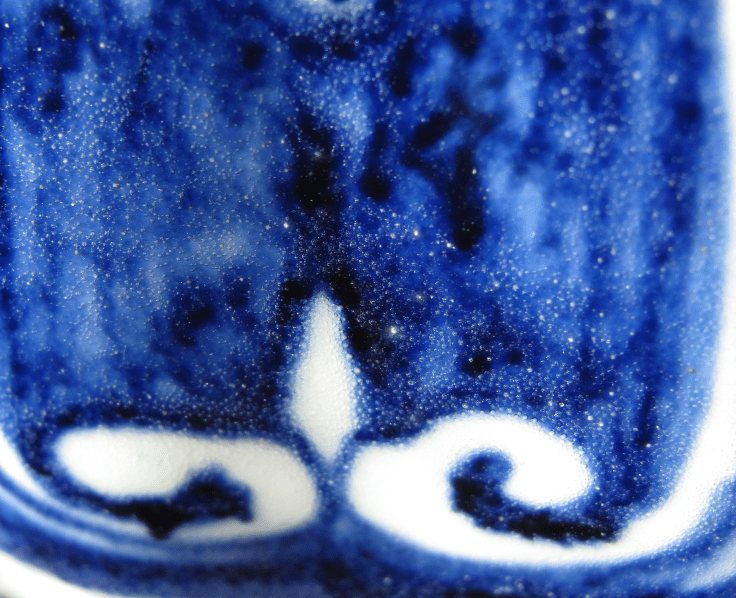

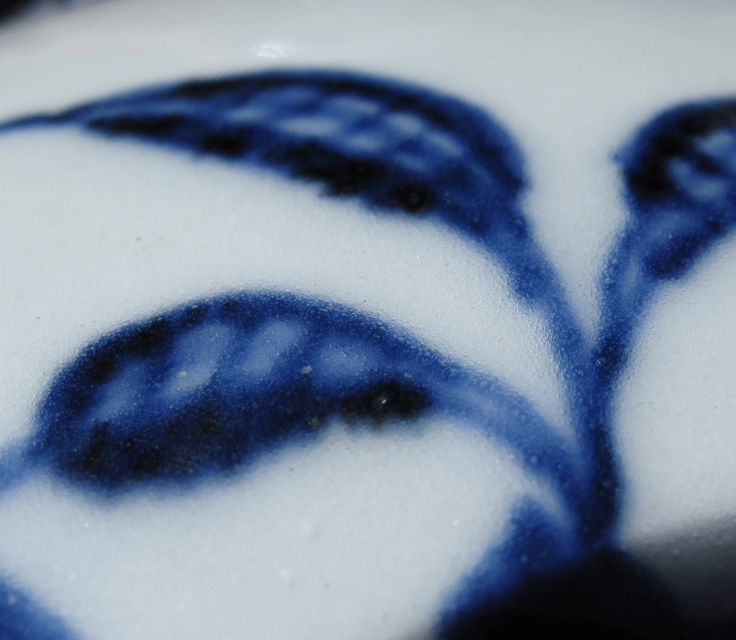

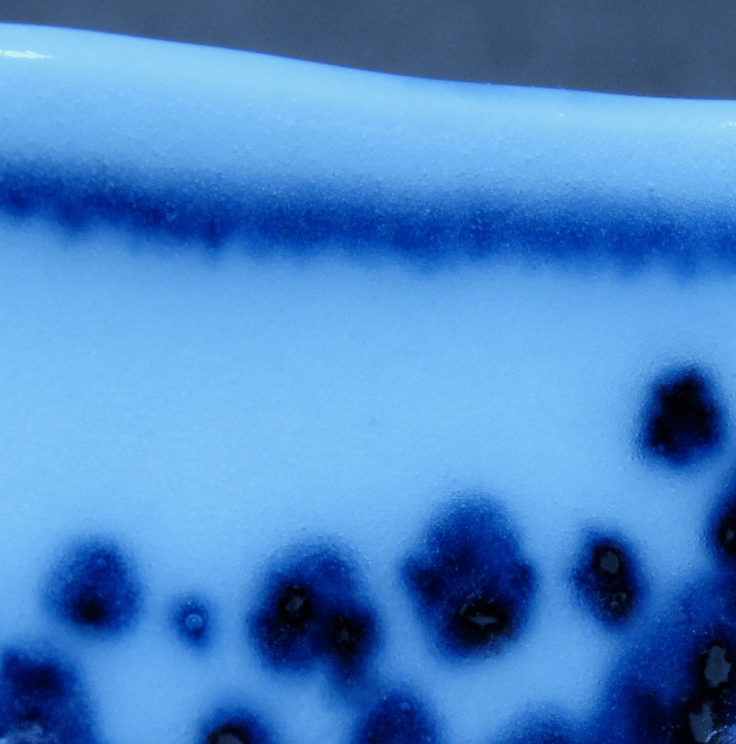

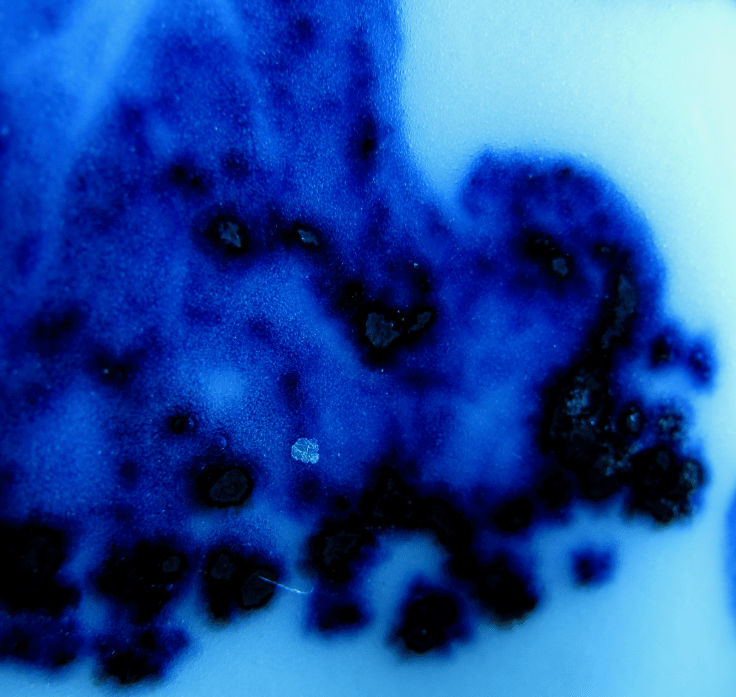

Note the plaques in these three photos (Figure 21-23). They are small, but some of them are distinctively reflective. You may also want to take this opportunity to study the flare and the dripping. I don’t believe that I need to dwell on them. And you will also note the bubbles. You have large bubbles, and rather small ones, ones that you’ll see in the Somali Blue dye. But I’ll show you more typical ones (Figures 24-27).

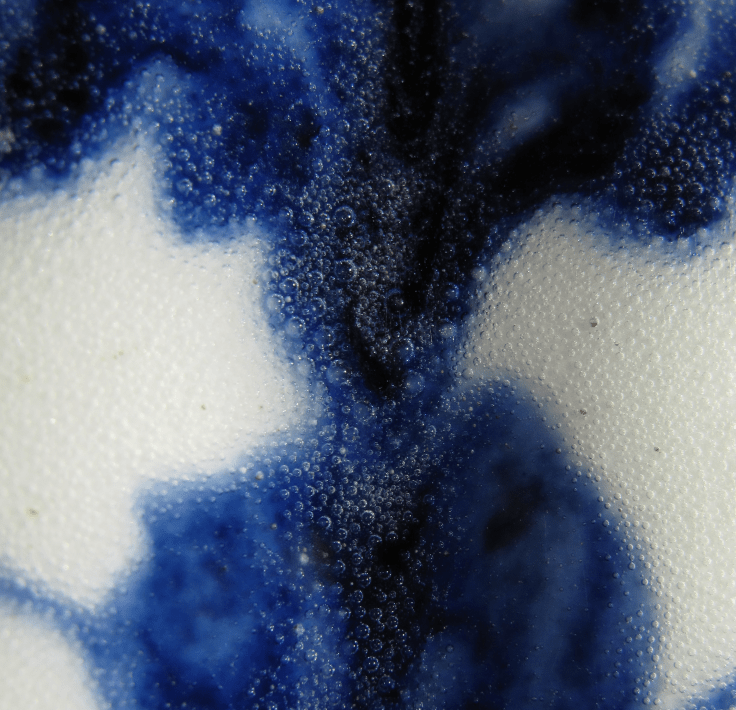

Figure 24

Figure 24

Figure 25

Figure 25

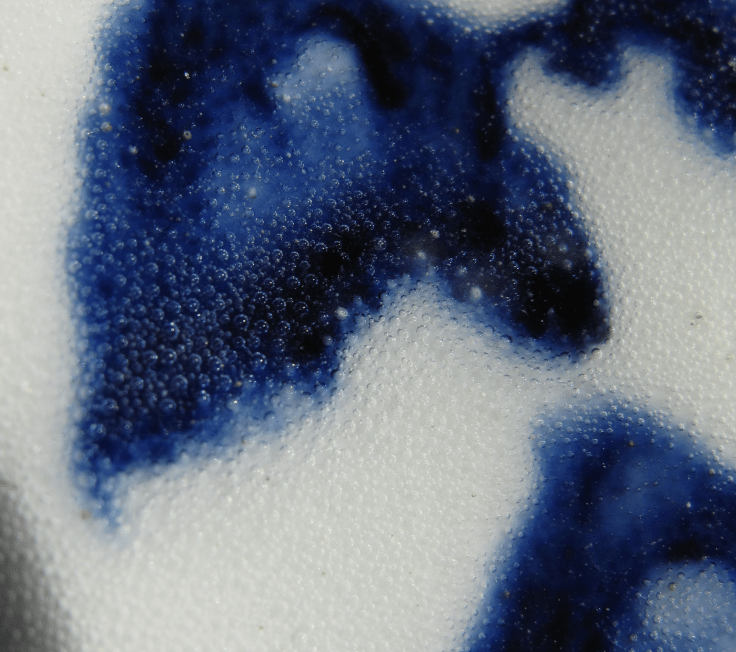

Figure 26

Figure 26

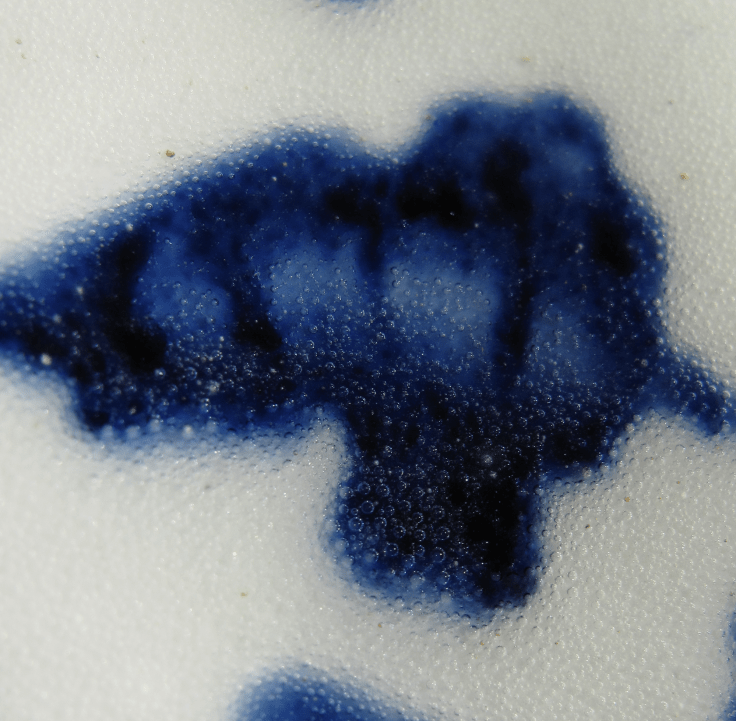

Figure 27

Figure 27

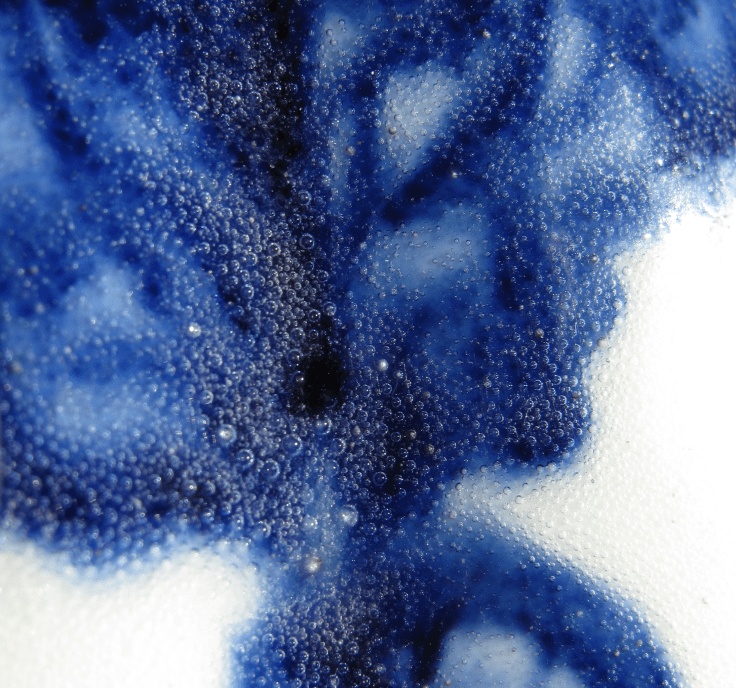

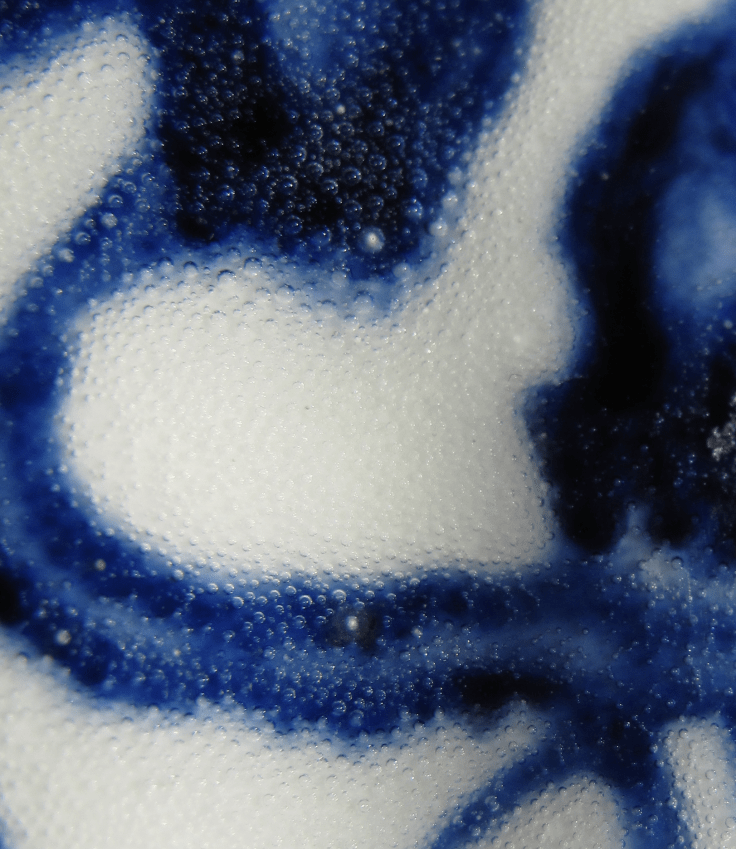

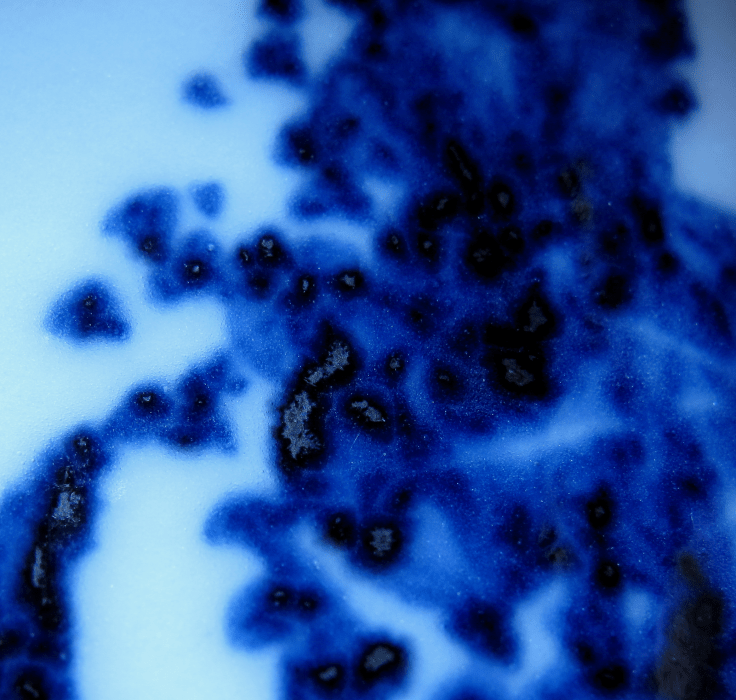

In these photos, do you not notice the large and small bubbles? The beautiful lacunae formation? Bubbles being linked up by short chains? And in Figure 26, the long string of large bubbles at the bottom? These are all so typical of the Somali Blue dye pigment, and their presence will lead you to the solid conclusion that the dye indeed in Somali Blue, and the ware has to be from the Xuande period. Before leaving this topic on bubbles, I’ll show you one more photo taken at the tuning peg (Figure 28). Note the tightly packed bubbles all trying to get to the surface, the dripping, the white-wash effect. Are these consistent with the Suymali Blue dye?

Figure 28

Figure 28

There is one more thing that I want you to note in this ware. Do you see in many of the photos here, you can find crackles here and there. Not the extensive fine crackles that you see in Ge wares or Guan wares in the Song era. Rather, the crackles are much less extensive. But in Xuande Blue and White, this is something very uncommon. We don’t know why, all that we need to know is that this is no ground for rejecting this pipa as a real and genuine Xuande.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3  Figure 4

Figure 4  Figure 5

Figure 5  Figure 6

Figure 6  Figure 7

Figure 7  Figure 8

Figure 8

Figure 11

Figure 11  Figure 12

Figure 12  Figure 13

Figure 13 Figure 14

Figure 14  Figure 15

Figure 15  Figure 16

Figure 16  Figure 17

Figure 17  Figure 18

Figure 18  Figure 19

Figure 19  Figure 20

Figure 20 Figure 21

Figure 21  Figure 22

Figure 22  Figure 23

Figure 23 Figure 24

Figure 24  Figure 25

Figure 25 Figure 26

Figure 26 Figure 27

Figure 27  Figure 28

Figure 28  Figure 29

Figure 29

Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3

Figure 5

Figure 5  Figure 6

Figure 6 Figure 7

Figure 7 Figure 8

Figure 8  Figure 9

Figure 9 Figure 10

Figure 10 Figure 11

Figure 11 Figure 12

Figure 12 Figure 13

Figure 13  Figure 14

Figure 14 Figure 15

Figure 15 Figure 16

Figure 16 Figure 17

Figure 17 Figure 18

Figure 18 Figure 19

Figure 19  Figure 20

Figure 20 Figure 21

Figure 21  Figure 22

Figure 22 Figure 23

Figure 23 Figure 24

Figure 24  Figure 25

Figure 25 Figure 26

Figure 26 Figure 27

Figure 27  Figure 28

Figure 28 Figure 29

Figure 29

Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3  Figure 4

Figure 4

Figure 6

Figure 6  Figure 7

Figure 7 Figure 8

Figure 8  Figure 9

Figure 9  Figure 10

Figure 10  Figure 11

Figure 11  Figure 12

Figure 12  Figure 13

Figure 13  Figure 14

Figure 14  Figure 15

Figure 15  Figure 16

Figure 16 Figure 17

Figure 17  Figure 18

Figure 18  Figure 19

Figure 19  Figure 20

Figure 20  Figure 21

Figure 21  Figure 22

Figure 22 Figure 23

Figure 23  Figure 24

Figure 24  Figure 25

Figure 25 Figure 26

Figure 26

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2  Figure 3

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4  Figure 5

Figure 5  Figure 6

Figure 6  Figure 7

Figure 7 Figure 8

Figure 8  Figure 9

Figure 9 Figure 10

Figure 10  Figure 11

Figure 11  Figure 12

Figure 12 Figure 13

Figure 13 Figure 14

Figure 14

Figure 16

Figure 16 Figure 17

Figure 17  Figure 18

Figure 18 Figure 19

Figure 19  Figure 20

Figure 20 Figure 21

Figure 21  Figure 22

Figure 22 Figure 23

Figure 23 Figure 24

Figure 24  Figure 25

Figure 25 Figure 26

Figure 26