I have told you that plaque is an important feature of the Sumali Blue dye. In some Blue and White wares of the Yongle period, plaques are plentiful. In some cases, they are not only plentiful, but they are really beautiful. I am going to show you a ware that bears these beautiful plaques. Mind you, however plentiful the plaques are in the Yongle B & Ws, they are a lot less than many of the late Yuan B & Ws.

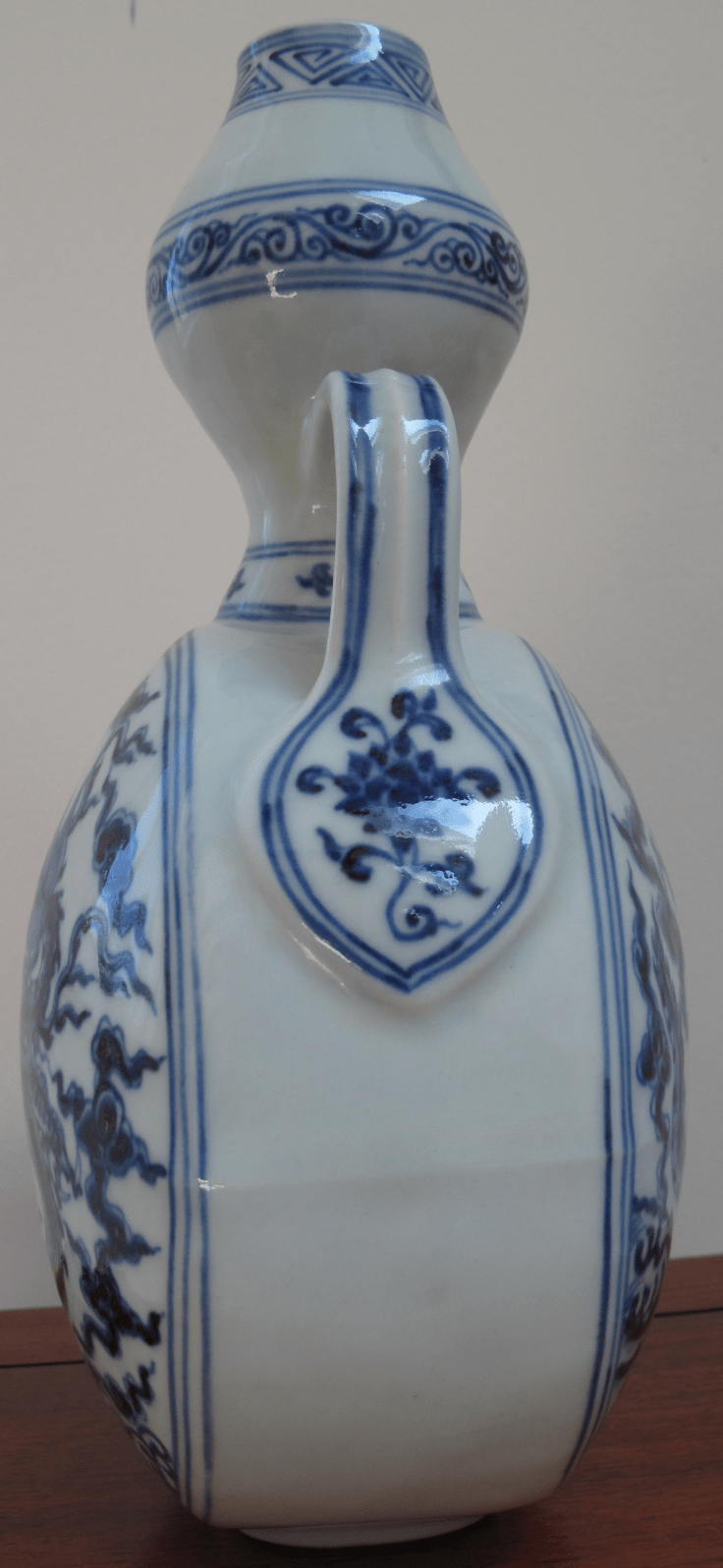

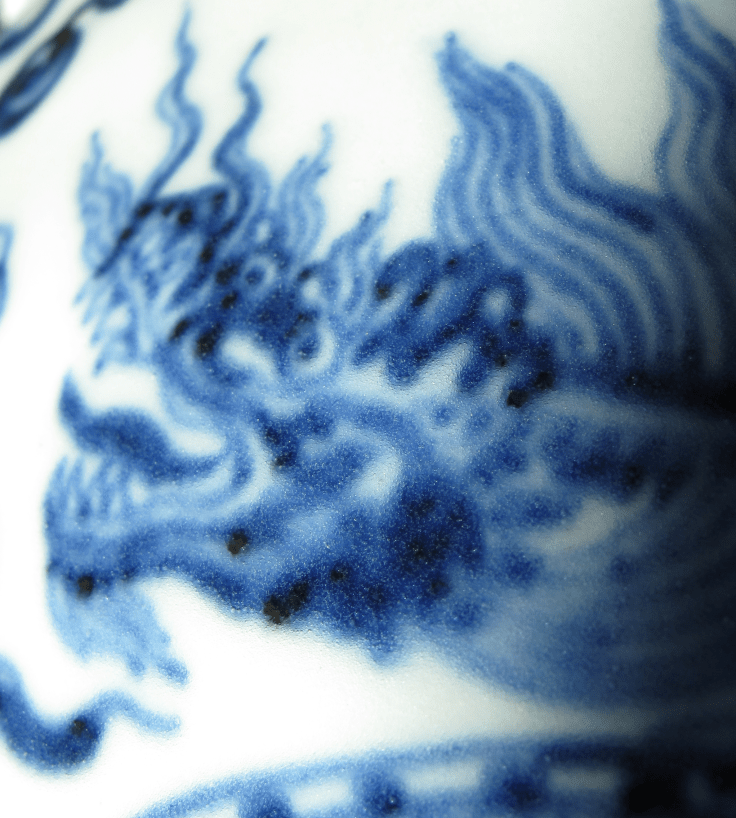

This is a Blue and White Yongle Dragon Moon Flask, Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1

Figure 2

It measures 26.5 cm in height. Now, Yongle’s moon flask is a very well sought after item for ceramic collectors. This is especially true with the dragon design. It is common knowledge that the Chinese have a special liking for the mythical beast dragon, so much so that they call the robe for a king the ‘dragon robe’, or the robe for a dragon, equating the king to a dragon. So, when the potters decided to have a dragon as their motif in a certain ware, they paid particular attention to the making of it. The chances are the ware would be of a superior quality. As you can see, this flask has got a very nice blue color and the dragon drawn very much alive. But in the eye of collectors, a ware with a nice color and a lively motif does not mean that it is genuine. So how can we tell that this is a genuine Yongle and of the period?

I’ll skip all the conventional way of evaluating this moon flask. Since I have labelled it as a Yongle, the blue dye used has to be the Sumali Blue dye. All that we need to do to justify the verdict that it is a Yongle is to show that the dye bears all the characteristics of the Sumali Blue dye. And this is what I am going to do. Once the dye is right, we do not need provenances to say that it is a Yongle. My experience is that, once the dye has all the features of the Sumali Blue dye, all the conventional ways of appraising the ware as a Yongle will fall into place. Everything just fits in.

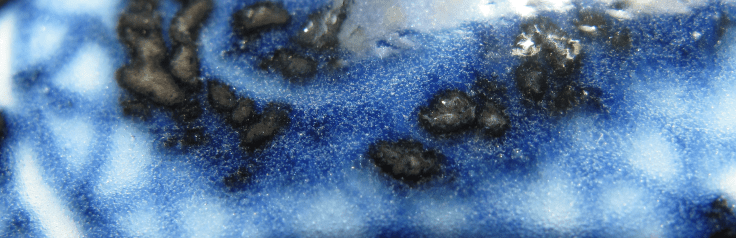

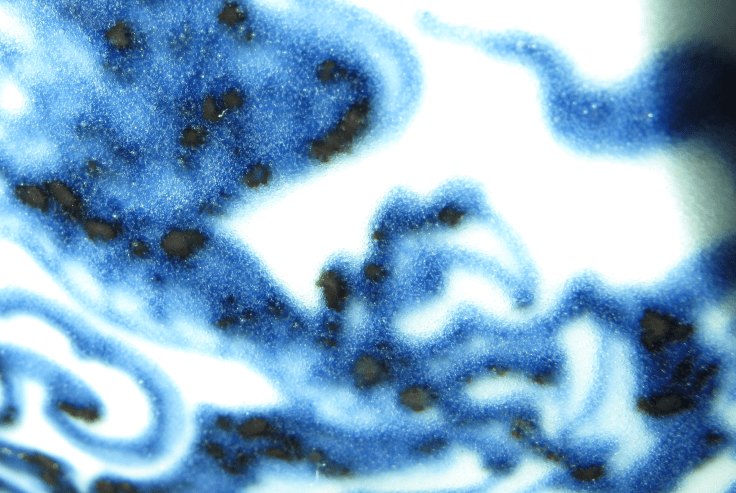

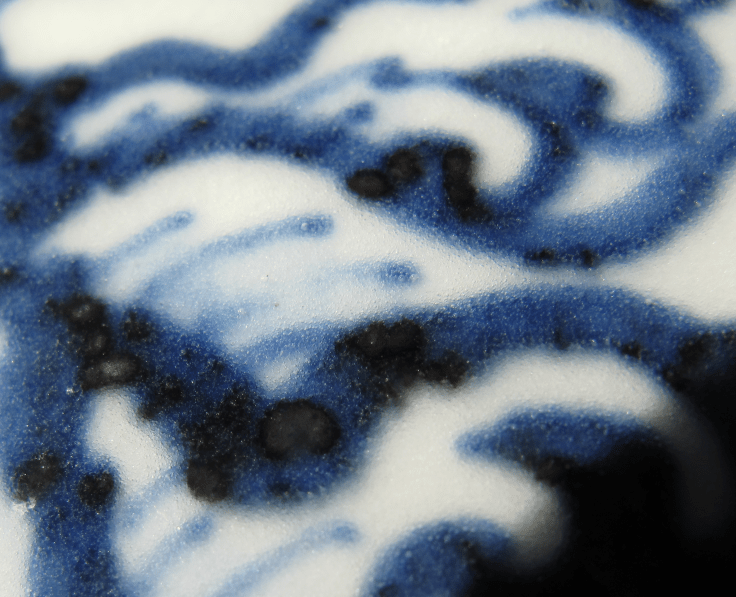

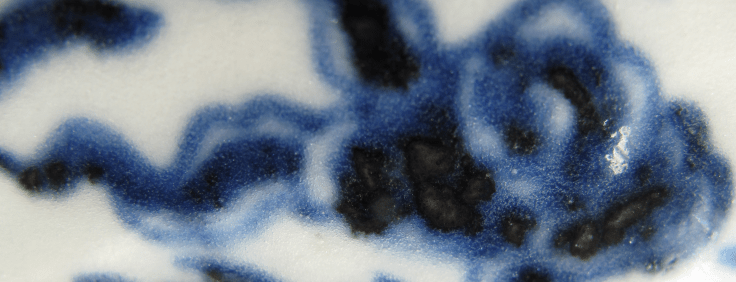

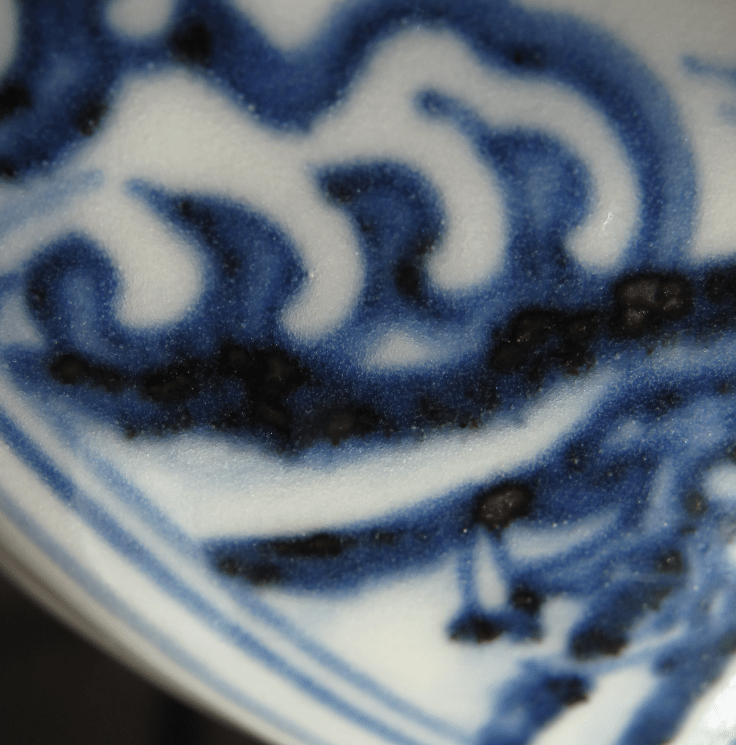

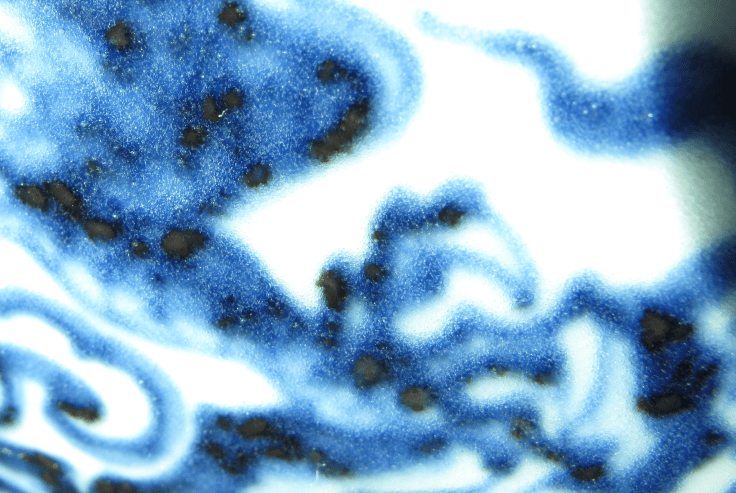

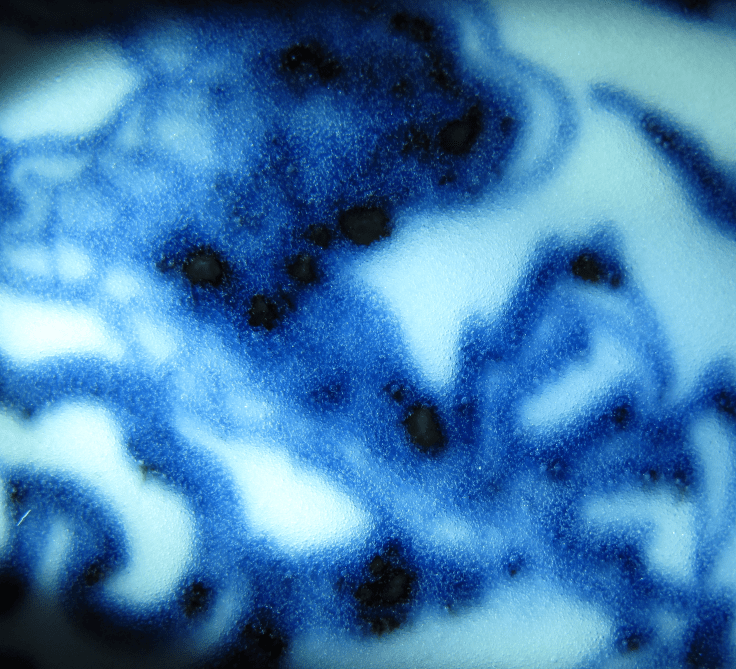

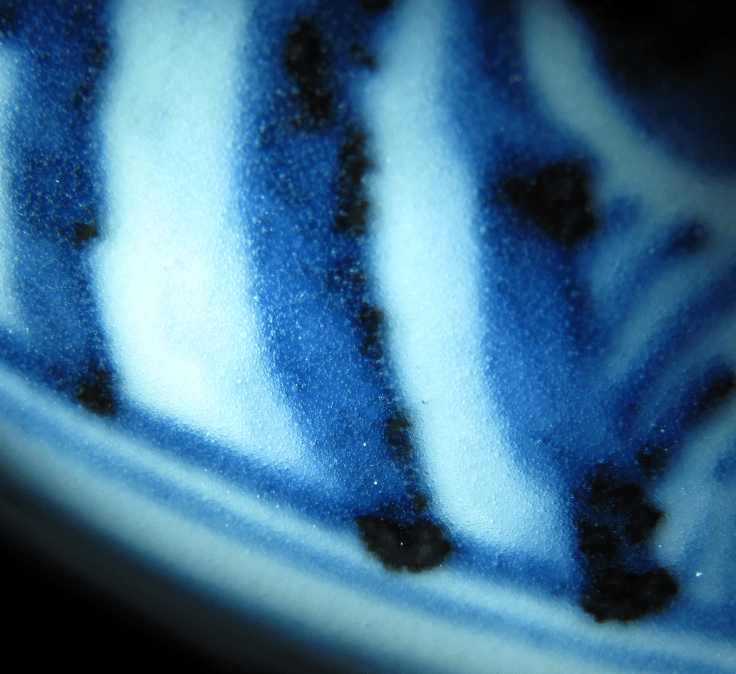

Since this moon flask has a lot of plaques, I’ll starting showing you the plaques first.

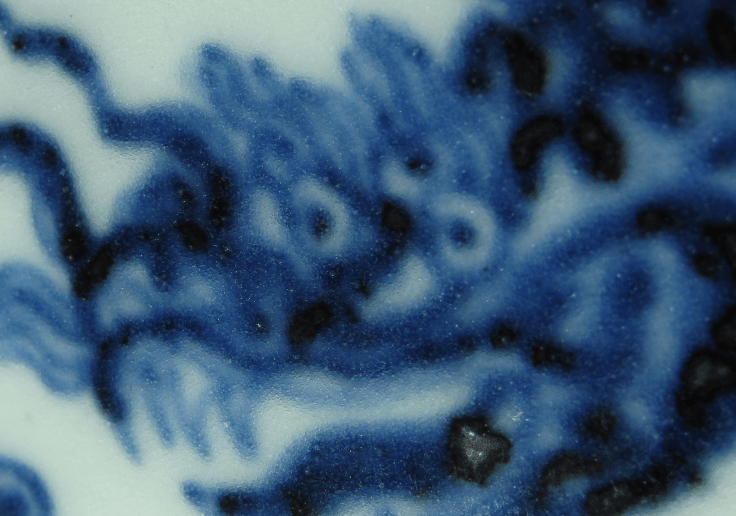

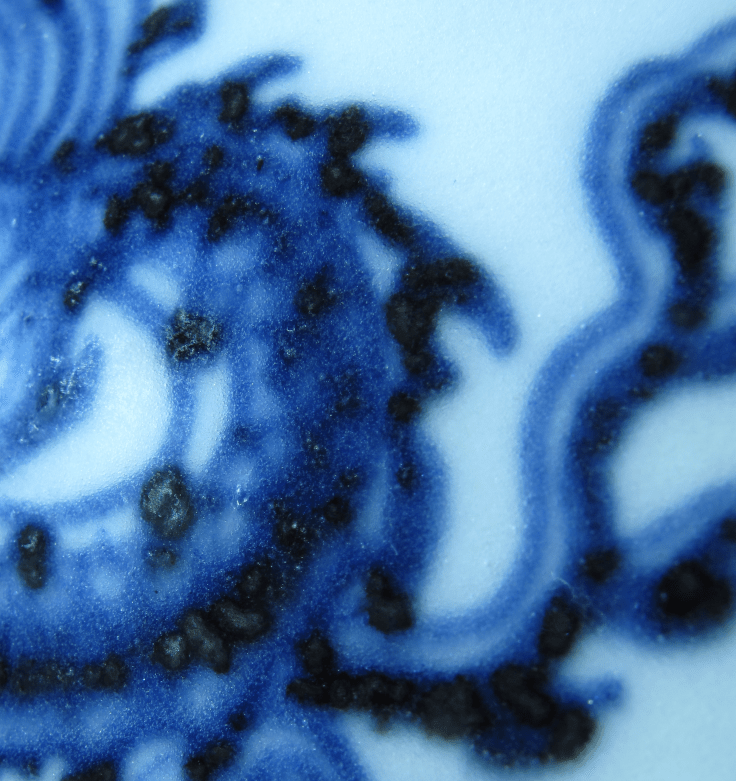

Figure 3

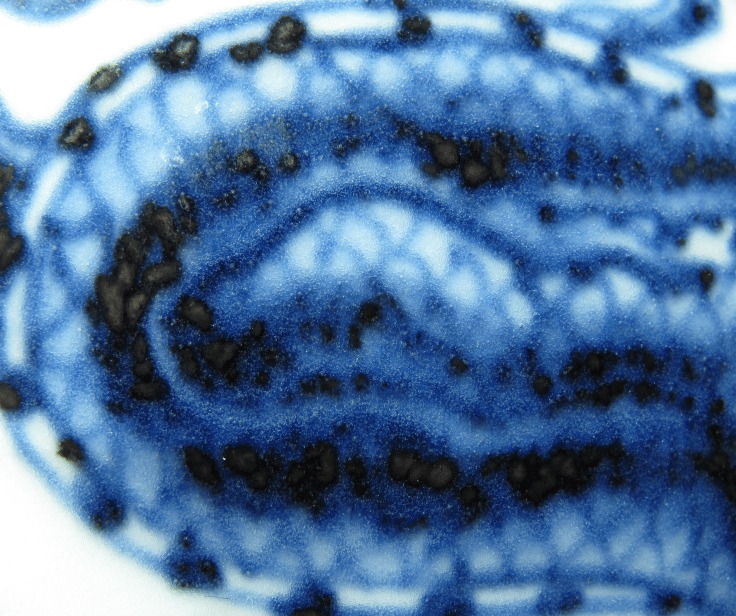

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

In Figures 3-7, I am trying to show you the abundance of plaques in this dragon moon flask, and how beautiful these plaques are. You should also pay attention to the color of these plaques. To get a general impression, you should go back to Figure 1. There, the plaques are not eye-catching at all. They just appear blackish in daylight. They are only apparent when you examine them under direct sunlight, all the while tilting the flask in different angles against the sun. Then, at certain angles, you can see the bright reflection of these plaques, displaying an array of different beautiful colors. Compare Figure 5 and Figure 6 carefully, and you can realize the effect of sunlight on these plaques. I must remind you that plaques have a very varied appearance in different wares, and you must be prepared that in other wares, the plaques would take other forms that are very different.

At this stage, when we are talking about the beauty of the plaques, you must be wondering what these plaques are? In other words, what is the nature of a plaque? How is it formed? Does it have specific compositions? If we are to go through literature, you will be surprised to find that noting much is said about these plaques. Not in English. Not in Chinese. The English term ‘heap and pile’ apparently implies that these plaques are formed by heaping and piling up of the dye pigment, and nothing much more is said about it. The Chinese call them ‘rusty iron marks’, and the meaning is self-explanatory. But is it really rusty iron that we are talking about? I don’t believe that one should be serious about these abstract descriptions by the Chinese. But there is one observation that these critics made is correct—over the larger plaques, if you are to feel with your finger tip, you will note a slight depression.

In the conventional evaluation of B & Ws that is painted with the Sumali Blue dye, it is important to make sure that there is a depression over the plaques. This is elementary. But as to the reason why there is a depression there, no one can give a good answer. Some have suggested that the Sumali Blue dye pigment has corrosive power, and that it corrodes the clay of the biscuit that is beneath it, thus causing the depression. To me, this is unlikely, and we must think of another more reasonable explanation.

Before we get on to with this, it is perhaps more helpful if we were to understand the nature of the plaques first. To understand the plaque, we need to know the dye pigment, which is the mother of the plaques. Unfortunately, we know very little about the dye pigment. We don’t even know where it is from. We don’t know the exporters, we don’t know where they lived. The only thing that we know about the dye pigment is that potters in China imported it in batches. When one batch was used up, they ordered another batch. And history tells us that the quality of these batches of dye pigment varies greatly, as reflected by the color, the plaques and the bubbles, over the years the dye was imported. And I would not be surprised that even with the same batch, the quality can also vary.

The fact that we know very little about the dye should not deter us from making some educated guesses as to the nature of the dye and its compositions and ingredients. From what we know, the dye was valuable and expensive. The exporters, unwilling to let the potters know the ingredients of the dye, must have ground them down into powder form. Initially, the powder must be quite coarse. With improvement of technology, the exporters eventually were able to make the powder much finer. We can tell this by the plaques in the Yuan B & W and those in the Yongle period, when the Yuan B & Ws have much coarser plaques.

But better technology does not mean better quality. Many collectors feel that the best B & Ws of all times are those made in the Yongle period. They have the best color, the best bubbles and plaques, though in the Yuan and Xuande periods, we do see some very nice ones too. This can only mean one thing: the exporters had every intention to improve the quality of the product. The wanted to use better ingredients. But eventually they found that using better ingredients would make the cost so prohibitively high that no one could afford it. They scaled back and used less expensive ingredients. In making this hypothesis, we know we are not talking about cobalt alone. There must be some very important ingredients that are included in the dye pigment, ingredients so uniquely beautiful and so expensive. We can actually go one step further to speculate that some of the ingredients are so expensive and so rare that the exporters finally gave up the idea to continue producing their product, for they were not able to find the very rare ingredients. That is why, after the rule of Xuande, there were no more exports.

We have yet to find out what these rare and expensive ingredients might be, but we are certain that they are responsible for the beautiful blue color, the plaques and the bubbles that B & Ws of those times have, for no replacements of the blue dye thereafter bear such characteristics. As I have stressed all along, the ingredients of the dye vary much even within that several decades when potters used the Sumali Blue dye. That translates into great variation in quality of the final product. So when we try to take to the task to making intelligent and educated guesses as to how the bubbles and plaques come about, we must specify the ware. Not wares in the same period, but that particular ware. Say for example, a Yongle B & W that only has large and small bubbles, what are the ingredients? I would say, the ingredients must have at least two components. One that gives rise to small bubbles, and the other large bubbles. I think that is simple logic.

To be specific about these special features, let us get back to this dragon moon flask and the bubbles and the plaques that it has. Here, the bubbles can still be roughly grouped into large and small, though this distinction is not as clear cut as in some other cases. There is little doubt that the two groups are from different ingredients within the Sumali Blue dye pigment. Let us concentrate on the large bubbles. Look at them carefully. Almost all of them are located in some deep blue color areas and around the plaques. In some cases, under careful examination and under strong light, you can actually see quite a number of large bubbles huddled together around a plaque. However, we often overlook this because the dark background has obscured the bubbles.

How are the large bubbles related to the plaque? Without knowing what the ingredient is, the best that we can do is to make some educated guesses. It seems to me that the plaques are always surrounded by some very dark coloration, and beyond that the color becomes deep blue. That might very well mean that the dark color and the deep blue coloration are from the same ingredient. When the concentration of the ingredient is high, the color is deep blue, and when the concentration gets really high, the color becomes black. What if there is more of the ingredient aggregated there? A plaque is formed. If we were to say that this same ingredient also gives rise to large bubbles, the hypothesis fits the picture perfectly.

If we were to look at things this way, the plaques are not from impurities, as some have suggested, but rather, they are from the dye pigment itself. If this were the case, how is a plaque formed? There is no way for us to find out. All that we can do is to approach the problem with common sense.

The dye pigment, when it was imported, must be in fine powder form. In using it, the potters must dissolve the pigment in water. From what we can gather from the appearances of the dye, the pigment is only partly soluble. That is to say, some of the fine powder remains insoluble, and it is now in suspension. When the potters painted the motif, they must be using some sort of a brush. When they painted, some of the fine powders were left along the line they drew. In some areas, there were more powder, in some, no powder at all. What happened when the painting was completed, and was left to dry and then covered with glaze and baked in the kiln? The powder that was left along a line, say, would melt under high temperature, and spread out. How far would it spread out from the original point? It all depends on the amount of fine powder there. But it would spread out. And this is the flare that we see in a B & W made in those periods.

In areas where the potters were making broader stroke, say the petals of a flower, what would happen? Naturally, there is a bigger chance that more of the fine powders were left in a particular spot. The final presentation of those areas that are left with the fine powders would be dependent on the amount that is left there. If not too much is left in the middle of a patch, that area would have a deeper blue color, with perhaps some large bubbles. When the amount is larger, the deep blue area becomes black, and a primitive plaque is formed.With more accumulation of the fine powder in a particular area, there will be a time when a full fledged plaque is formed. So, how does it look like?

I have observed many, many plaques. I would say this: though the appearances of plaques vary through a wide range, but basically, they are formed in similar manners. You would always find large bubbles associate with plaque, and the deep blue coloration. When plaques are about to form, they always have the black color as the backdrop. As the plaque matures, you begin to see the plaque forming within the black patch. As it matures, the plaque takes many forms. But one thing is in common, they always show reflections under the sun—at a certain angle. that is why when examining a plaque, you should do it under the sun, and don’t forget tilting the ware in different angles against the sunlight. At some point, you’ll see the reflection.

Just look at Figure 3-6, and you know what I am driving at.

In many Yuan B & Ws, the plaques are not only abundant, they also have the appearances of small pieces of aluminum foil that are shining and spreading all through the ware. There is little doubt that they have in their composition quite a significant percentage of metallic content, for the reflection can be nothing else but of metallic origin. Looking at it again, it is tempting to think that aluminum is a major component of the plaque. But in literature, nobody seems to be interested in the composition of these plaques. It seems that they are presumed to have originated from some sort of cobalt compound. I have grave doubt on this. If the plaques were from cobalt, why are the subsequent replacement dyes, which are all cobalt ores, lack this very specific characteristics. That is why I would not be surprised that one day, when scientific study on the composition of the plaque is being carried out seriously, the results may confirm my speculation.

There is yet another important question concerning the plaques. The plaques lie within the thickness of the glaze. That is certain. But where in the glaze? Are they at the bottom of the glaze, lying just above the clay of the biscuit? Or are they at the top of the glaze layer, or somewhere in between? The answer is: none of the above. Why? It is because a plaque has quite a complicated structure. A mature plaque has, in fact, at least two components–a what I call a muddy layer that lies at the bottom just above the clay, and a shiny metal containing layer that floats at the top of the glaze.

When you look at a well-formed plaque carefully, you can be certain that there is a metal containing, aluminum-foil-like tiny sheet that floats right at the top, with just a very thin layer of glaze separating the sheet from the nearby atmosphere. That is why, you never find a large bubble on top of these shining plaques. There is no space for them, they are all displaced out. The fact that these shining plaques, when they float atop of the glaze, means that their specific gravity is smaller than the glaze itself. Can they be aluminum, which has a specific gravity of around 2.6? That can well be the case, because the glaze is very viscous and its specific gravity can easily be greater than that of aluminum. We’ll find that out one day. As to the bottom muddy layer, we will talk about it later on.

What happened to these tiny sheets when the baking was done? The ware in the kiln began to cool slowly, and the plaque, with a lot of metallic content, would respond by contracting down—at a rate faster than the glaze next to it. In contracting, the surface tension that it exerts on the glaze would allow it to cave in, creating a slightly hollow-out space right on top of the plaque. this is the reason why we can feel a slight depression on top of the plaque. It has noting to do with the corrosive power of the dye, as some have suggested.

The description above is, should I say, a simplified version of the structure of a plaque. In many cases, it is a lot more complicated. I’ll try to deal with the problem again when the time comes.

Figure 8

Now, look at Figure 8. It recaptures the points that I have made. Look at the small blackish patches. They are the primitive plaques. Then, the larger black patches. They begin to show plaques in their formation. A well formed plaque with light reflection is seen on the left of the photo. You can also see large bubbles that are really close together nearby. Now, I must draw your attention to the flare and dripping effect of the Sumali Blue dye. You can see that, on the lower side of each plaque, something diffuses out. This is flare. And when the motif is on the vertical part of the ware, the flare is exaggerated by the gravitational effect and becomes the dripping. As I have said, the fine granules of the dye, under high temperature, would melt and flare out and drip down slowly. The dark color, when it is further away from the origin and getting near the margin, becomes lighter and lighter, creating the visual effect that we see here. This dripping effect, even if it is in the vertical part of the ware and is fully affected by gravitational forces, should never be very severe. This is because the glaze is very viscous, and provides a natural resistance to the otherwise free down flow of the dye pigment. In all these photos, you too should pay attention to the large and small bubbles, and how they are distributed.

Figure 9

Figure 9 is a photo showing the plaques and the flares and drippings associated with them. Also note the metallic reflection. I have told you that large bubbles are from the deep blue and dark color portion of the dye. Look at the two large bubbles on the light blue line to the left of the main plaque. They are opaque bubbles, a typical presentation of these large bubbles. And look at them more carefully, enlarged the photo, and you’ll see some light blackish hue just above them. This is no mere coincidence, it just confirms that the dye is genuinely Sumali Blue dye.

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 10 and 11 are two more photos showing features of the plaques and flares and drippings. But here, I would like you to look at the bubbles—the large as well as the small ones. For those who are not very experienced, I would like to tell you that here, particularly Figure 11, the bubbles are really beautiful. To me, the number of large bubbles is just right, not too many, and not too few. They have the opaque appearance. They also occasionally have the appearance that they are strung together with a string—a really pleasing sight to the eyes.

When you say the large bubbles are nice, the small ones are equally, if not more, beautiful. Now, there are many small bubbles here. They might not be as dense as in some of the wares that I have shown you, but the density is high. But what is striking is that, dense as they might appear, you do not get a feeling of confusion here. I can tell you why. Enlarge the photo slightly, and you can see that the small bubbles are all in lacunae formation. A number of small bubbles, about 10 or so, seem to be mapping out a small space in a continuous and curvy line, giving the impression that there is an empty space surrounded by the string of small bubbles. Here in this photo, the lacunae are dense and you can see them clearly, but they are not in disarray. You can see lacunae in all B & W, no matter their periods, but they are a lot fewer than those wares made of the Sumali Blue dye. I would also like to add that, even when the Sumali Blue dye was used, lacunae as beautiful as seen here is rare. And remember, lacunae of this nature is characteristic of the dye.

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 12-15 are more photos to show you the lacunae. Try to pay attention to other features of the Sumali Blue dye in these photos. The large bubbles, the plaques, the flares and drippings and get yourself familiar with these characteristics. In trying to see the lacunae, as in these photos, you will get a better idea when you enlarge the photo slightly. But do not enlarge them too much, when you will lose the general impression.

In all these photos, I am trying to show you the special features of the Sumali Blue dye. In a ware where good quality dye pigment is used, many a time, just a single photo is enough to show you all those peculiar features, and just that photo alone is enough for an experienced collector to say that the ware is genuine, and I don’t believe any expert can dispute that. Before I leave this topic, I’ll just show you a few more photos—the mouth, the base and others of the same ware.

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

This last photo, Figure 20, has all the features that are sufficient to tell you that the dye is Sumali Blue dye. Look at the plaques, those that are in the various stages of formation, and those that are already matured. The large pearly bubbles, the small bubbles with lacunae formation, and the flares and drippings. And Finally, the beautiful blue coloration that is sapphire-like. And for those who are familiar with Yongle B & W, the moon flask is, without a doubt, a Yongle.