In my previous articles, I have told you that plaques are important features in the Sumali Blue dye. But these plaques show changes throughout the whole period when the dye was imported. During the Yuan Dynasty, the Blue and Whites have plaques that are abundant as well as prominent. By the period of Xuande, as I said before, some B & Ws have literally no plaques at all. It is, strictly speaking, incorrect to say that these wares have no plaques. They do, but what they have are not well-formed plaques, immature plaques, and I’ll call them primitive plaques. It sounds confusing, but I’ll elaborate here.

A well-formed plaque, or a matured plaque, has at least two components in its simplest description—a muddy layer at the bottom right on top of the clay biscuit, and a shiny metallic foil floating on top of the glaze with a small gap in between them. The width of the gap is dependent on the thickness of the glaze, so that the distance separating the two layers varies under different conditions. The metallic foil, to me, looks like aluminum, and in all likelihood, it is aluminum. Some critics in the past used to say that the reflection from the metallic foil is tin reflection. I doubt it. Let us look at it this way. The specific gravity of aluminum is around 2.5, while the specific gravity of tin is around 7.5. I don’t believe anything with the specific gravity like tin can float atop the glaze, whereas if the glaze is viscous, it is easy for a tiny sheet of aluminum to float on top of it.

I have told you that the metallic foil, or should I call it aluminum foil, is formed by the aggregate of a lot of aluminum particles deriving from the dye pigment. When the aluminum content of the dye is rich, the aluminum foil will be large, covering up the bottom muddy layer. All that you can see in a plaque is the aluminum foil surrounded by a small pool of dark blue coloration. I have shown you that in the Yuan B & Ws. With decreasing amount of aluminum in the dye, the shiny layer gets smaller, allowing you to see part of the muddy layer. That is why, when the metallic content of the dye is very small, all that you see is the muddy layer with the aluminum particle still adhering to the ‘mud’ at the bottom. When you examine such plaques under the sun, at certain angles there is still very good reflection from those aluminum at the bottom, for aluminum has a very good light reflection, though the shiny layer is gone.

This theory also explains why in those large plaques with the aluminum foil on top, you can feel a slight depression over the foil with the tip of your finger. There is a reason for this. When, at the end of the baking of the ware in the kiln, the aluminum foil is still a flat piece floating on top of the glaze. However, when the baking process is done, the ceramic ware begins to cool down, affecting both the aluminum foil and the glaze on which it floats. Our knowledge in physics will tell us that the metal contracts more than the glaze in the cooling process. This greater contraction together with the surface tension and other forces, would bend the metal in a concave manner, giving rise to a small depression on the surface of the ware that we can actually feel with the tip of our finger.

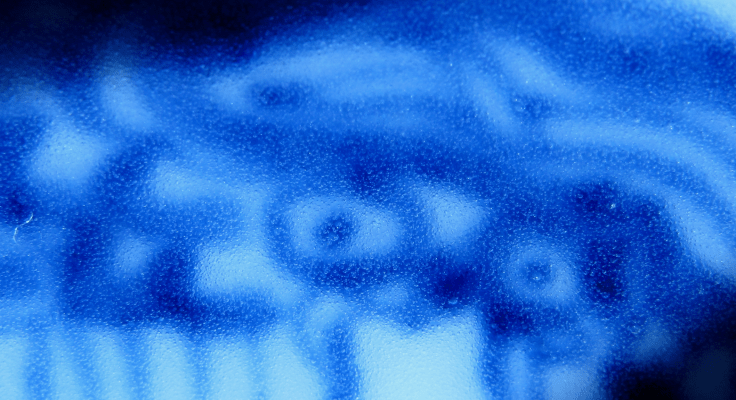

With all these in mind, it is not difficult to identify a matured plaque, and hence the identity of the dye as Sumali Blue is established. But when there is no matured plaque, when there is not even the presence of a muddy layer, and when circumstances are such that we still suspect the B & W to be a Xuande, how are we going to arrive at that verdict? In such a circumstance, what we should do is to look for what I call the primitive plaque. What is a primitive plaque? How does it look like? This is exactly what I want to tell you here, not so much with words, but with photos of this Xuande bowl (Figures 1-3). The bowl measures 8 1/4 inches in diameter.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 7

Figures 4-7 are taken from the side of the bowl, from the rather small dragons on the panels. You can immediately see small dark blue, almost black patches here and there. These are the primitive plaques. Blow them up and look at them carefully. Inside the black patch there is an element of dark brownish hue. It is quite irregular with poorly defined borders. It is what I call the primitive muddy layer. Even under the sun, no matter at what angle you are going to tilt the bowl, there is no noticeable shiny reflection. I suppose the metallic content there is very low, and whatever is present, is not enough to generate reflections that can be seen with the naked eye, or by the camera. But, as in any matured plaque in the Sumali Blue dye, you can see large bubbles in adjacent areas. You can also see these large bubbles in other blue color areas that are of a darker hue. Because of the limited dye and fine strokes the potters used in these small dragons, the small bubbles are not well seen, not to say the lacunae. Before I show you these features, which can be seen in the larger dragon at the bottom of the bowl, let me just show you a few more photos of the primitive plaques (Figures 8-10).

Figure 8

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 10

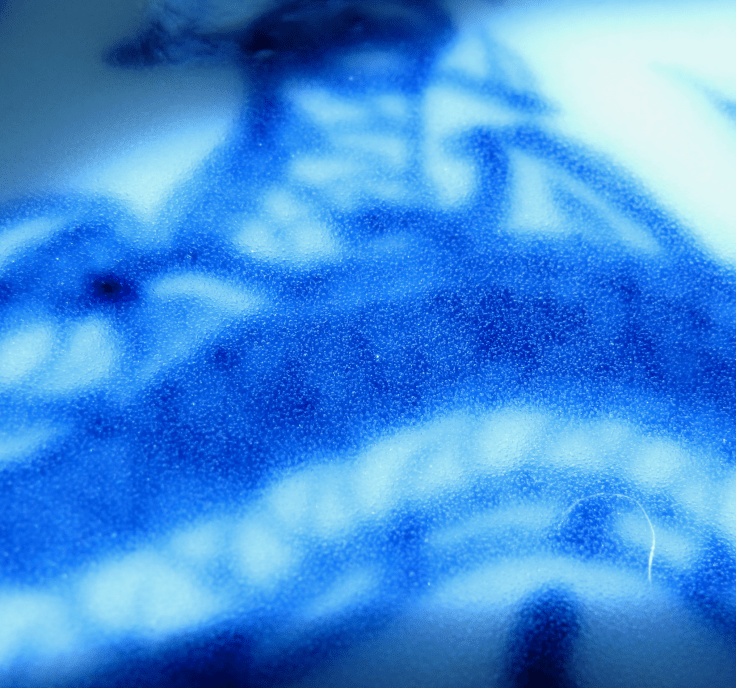

I’ll now show you photos of the large dragon that is at the bottom of the bowl (Figures 11-14). Now, in these four photos, because of the larger drawing and hence the more liberal use of the dye, the large and small bubbles are well seen. Look at the dragon eyes with large and semi-translucent bubbles, these are the classic signs of the Sumali Blue dye. And you can notice again that the potter was paying attention of the eyes, even as they are in the bottom of the bowl, a site where collectors might not be paying good attention. You should also like to look at the lacunae formation.

Figure 11

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 14

To complete the picture, I’ll now show you the flare and dripping (Figure 15-17). In figure 15, the dripping is particularly obvious. You can see the part of the primitive plaque that is dripping down, in some areas fading into a slightly greenish and light black/bluish hue. Note also the large bubbles and primitive plaques in other areas.

Figure 15

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 17

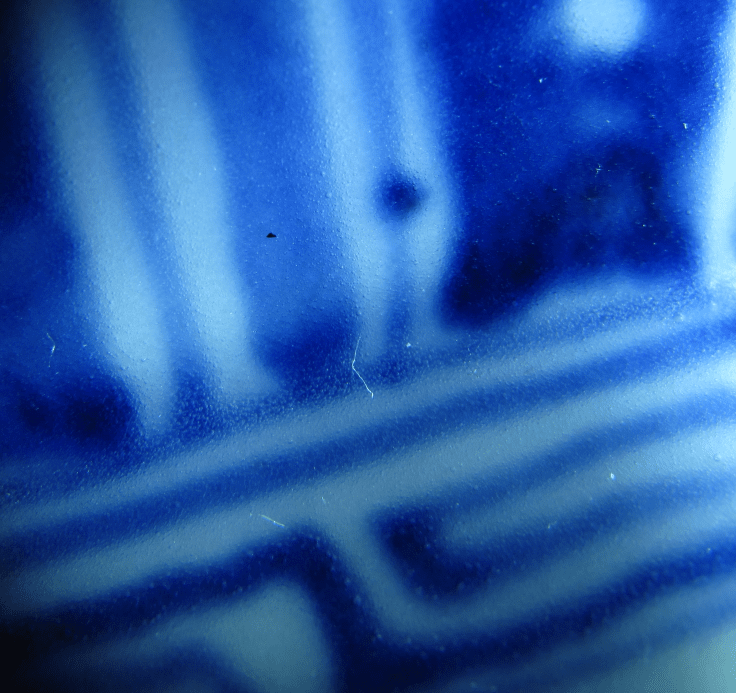

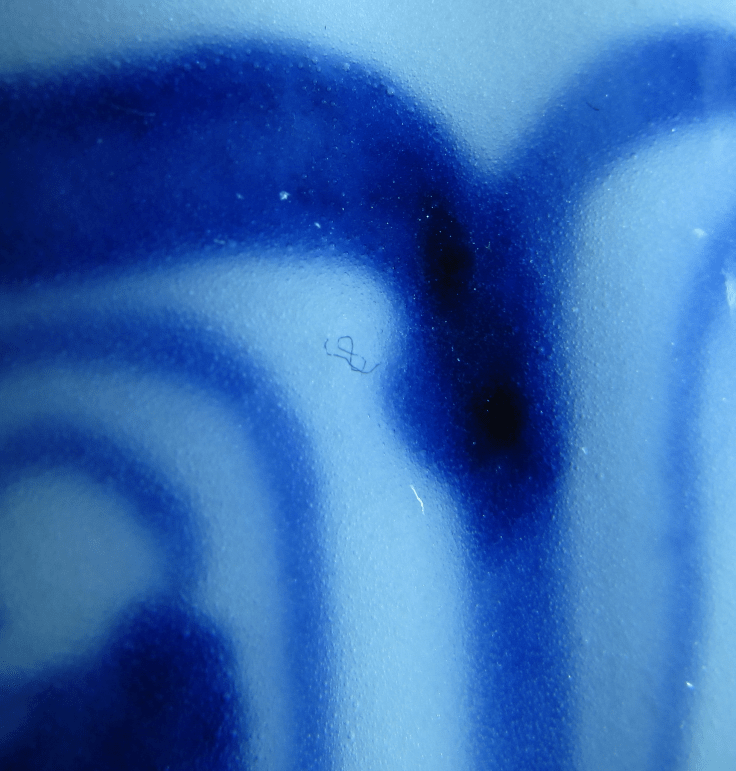

There is another area where the dripping is usually very obvious in many of the B & Ws that are drawn with the Sumali Blue dye. It is in the decorative lines near the mouth of the ware (Figures 18-21). Pay attention to all the B & Ws in those periods, most of the time, the dripping is easily noticeable. If the lines are straight with no dripping, you should raise your suspicion right away. It is also most common to find some parts of the line in a lighter tone, what critics used to say is from the bleaching effect on the dye by the glaze. It is highly likely that this is another mis-representation of the facts. I don’t believe the glaze has any bleaching property. The lightening of color is in fact due to over-application of the glaze at the mouth at certain parts, allowing more glaze to flow downwards at that particular site to wash away the dye pigment there. This results in lightening of the blue color.

Figure 18

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 21

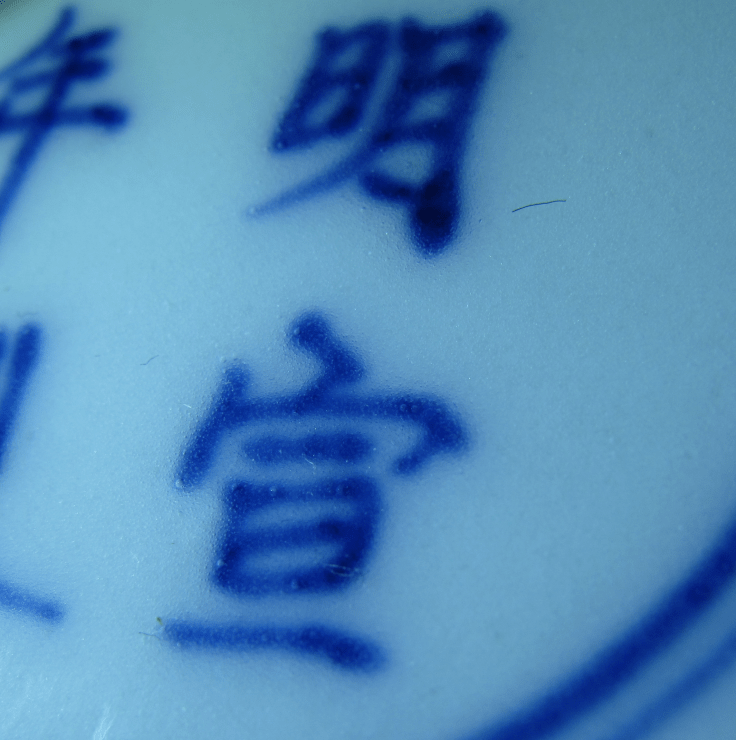

Here, I’ll also show you the Xuande mark. The bubbles there are typical. With the mark, and every other thing that I have shown you here, even there are no matured plaques, we should feel confident that this bowl is a genuine Xuande.

Figure 22

Figure 22