Many a time, when you go to a museum, you see something very beautiful. It may be a painting, it may be a ceramic ware. Since you are a ceramic lover, let us presume the beautiful item is an early Ming Blue and White. It is so exquisitely beautiful that you promise yourself that you’ll go back there again just to look at the ware one more time and to appreciate the beauty of it. And frequently you’ll wonder if some other museum has a similar piece. The caption is normally very brief, and will seldom say if it is rare or not. As a collector, you are often very concern about the rarity of an item. If it is extremely rare, you tend to pay more attention to it. But there is no way you can tell for certain.

In this aspect, the big auction houses have done us a big favor. When a rare item is auctioned, they would tell you and advertise that it is rare, very rare, or extremely rare. This is very important to big-time collectors. They want to have an item that is so unique that you can never find another similar item anywhere in the world. The auction houses are also very much interested in this, for rarity and auction price go hand in hand, the more rare the item is, the more money it can fetch. And big auction houses have the resources to make in-depth research to find out if the item is really very rare. They would go through all reference books, museum and famous collectors’ catalogues and other means just to make sure that the information that they give out is correct. When there are just two very similar items to the one that they are going to auction off, they would say in no uncertain terms their findings: that these two wares are the only two other wares known to the world similar to the one that is being auctioned. They would then give details as to where the two others can be found. And the rarity of the item can be quantified.

There is just one slight catch here. In declaring that there are just two similar items known to the world, they are making an assumption. We all know what the phrase ‘known to the world’ means, and we all know the implications it carries. Simply put, it only means that these three are the only three wares with credentials, with provenances. All similar wares, though the chances of having a similar ware is extremely low after their extensive research, are without provenances and without merit, and thus are reproductions.

I have explained in my previous articles that in America there are many beautiful Chinese ceramics. They spread out in the homes of Americans. Not only in the homes of small collectors, but in the homes of those who are not collectors at all. They have just one or two very good pieces handed down to them from generation to generation. As a rough estimate, I would say that for every major big-named collector that we have, there are probably tens of thousands, or indeed hundreds of thousands of minor nameless collectors. Collectively, the number of ceramic wares they have must be tens and even hundreds of times more than all the collections of museums and major collectors combined. So that, a ware that is declared unique after exhaustive search in catalogues and museums may not be unique at all. There might be quite a few in existence outside this very restrictive sector of museum catalogues and major collections. I’ll not be surprised that there are beautiful and valuable wares among these small and nameless collectors that the world has not yet seen. Unfortunately, these are without provenance and their authenticity is always in doubt. Most experts would dismiss them summarily.

One word about provenance here. Provenances are, to me, only important when we do not have an accepted method to determine if the ware is real or not, when everything depends on experience. In such a case, we have no choice but to rely on provenances. If we do have something concrete to make a verdict, as we have now in determining the true nature of the Sumali Blue dye when we try to evaluate a B & W of the Yongle and Xuande period, provenances is no longer important.

Before I show you a rather rare B & W ewer of the Yongle period, it is perhaps pertinent for me to tell you my speculation as to why in America, there are so many fine B & Ws and other ceramic wares. History gives us little hint as to the reason. When history is not helping us, we need to approach the problem in another manner. My way is to adopt a common sense approach. There is no way to tell if my speculation is right or wrong, but at least it makes sense.

We have to go back for several hundred years. It was in 1557 that the Ming Dynasty gave consent to the Portuguese to established a permanent and official base in Macau. They must have been in some form of relationship for decades prior to that. It also means that the first westerners were doing business in China much earlier. These businessmen, when they go back home after a long stay in China, would bring along with them souvenirs. Many of these businessmen were rich, and they could afford expensive stuff. What better choice is there than ceramics, when it was in vogue in Europe at that time? They would buy the best ceramic pieces from the Chinese, who might have acquired their beautiful ceramics from their forefathers. But their declining family fortune had forced them to sell. That is why many beautiful pieces where brought back to Europe. This practice must have gone on for several hundred years, and after Mayflower, many of these pieces went to America with their owners. That is why beautiful ceramics is plentiful in America. America has much more nice ceramic pieces than most of us can imagine. But after so many generations, ordinary Americans today have no idea how beautiful and how valuable these pieces are, and they just sell them on the open market for very little money.

Now, let us go back to the ewer that I am going to show you. It is rather rare and measures 11 1/2 inches tall (Figure 1and Figure 2). When we talk about rarity, it is the shape that we often refer to. It seldom has to do with the decorative motif. Now, ewers are by themselves rather rare. You do not see them very often. But if you go to the Internet, most of the ewers are not of this shape. Indeed, on the Internet, I have not seen one similar to this. but as far as beauty is concerned, it is purely personal preference. For myself, I prefer this present one here.

Then comes the crucial question. When an ewer is as rare as this one, and without any provenance, how are you going to say that is is genuine and of the period? Some experts will dismiss it instantly, because they have not seen anything like that before. But I would say we should go back to the fundamental—to look at the blue dye pigment and see if it is of the Sumali Blue dye. That is the ultimate judgment.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 2

Let me just show you two photos of the ewer first.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 4

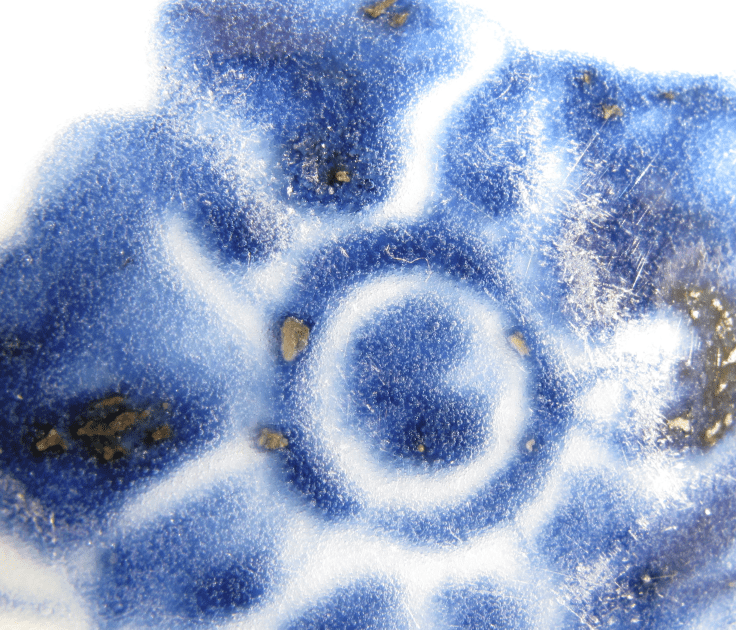

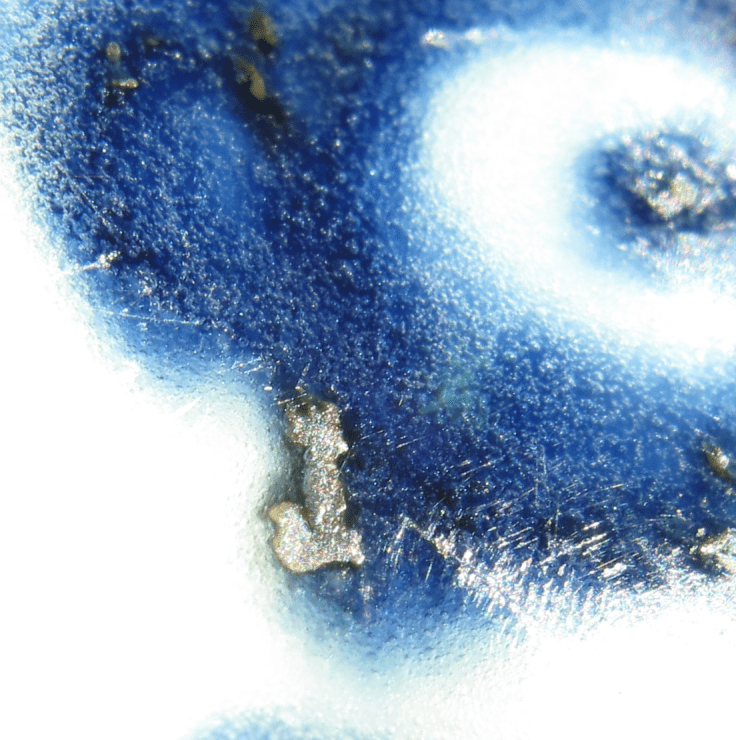

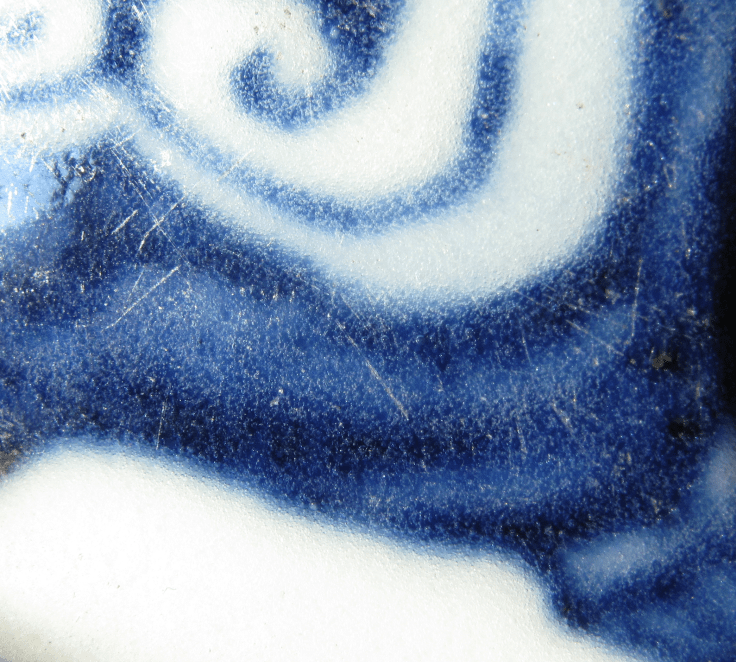

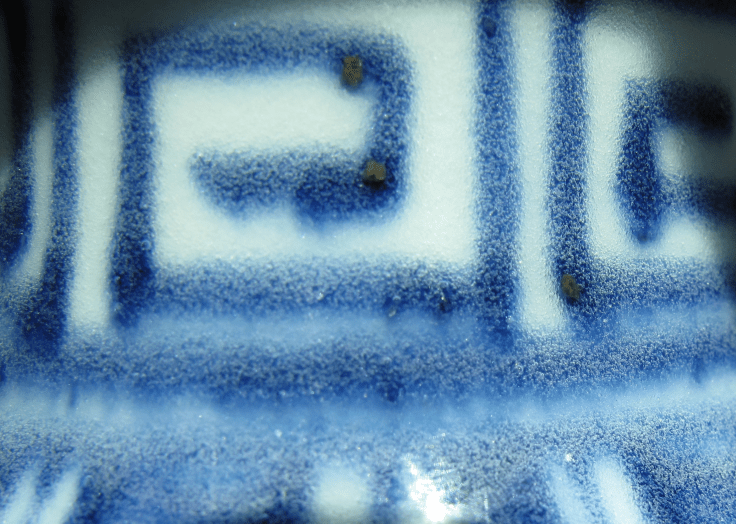

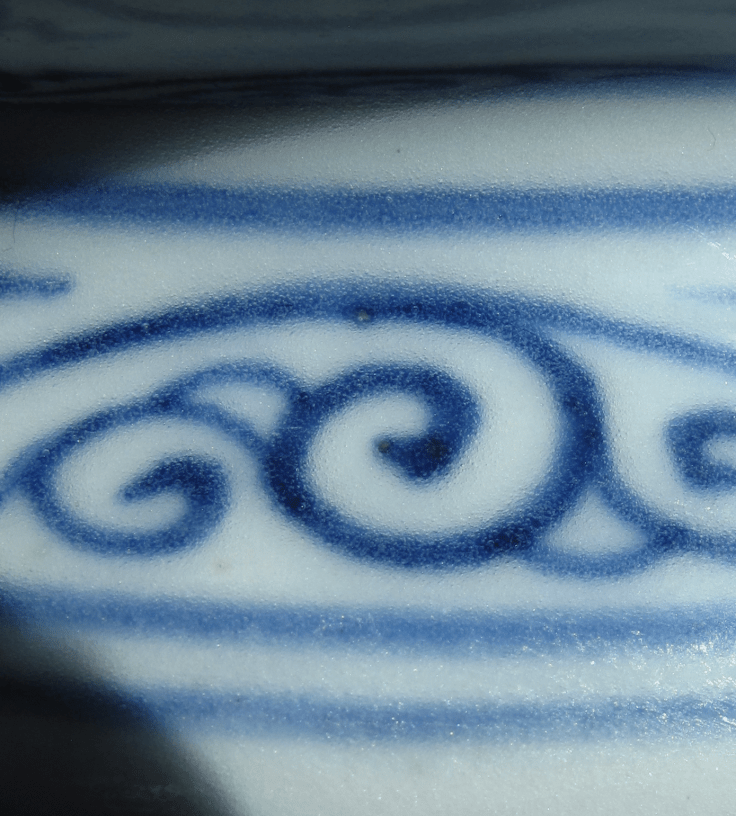

Figures 3 and 4 are not really close-up photos. But they give you a general impression of how the blue dye behaves and some of its characteristics. The plaques are obvious. There are large and small bubbles. Even the lacunae can be seen. And if you are to look at the margins of the dye, flare and drippings are also well seen. Look at the right upper hand corner of Figure 3, a gourd shape patch is seen. What do you think it is? In fact, it is some abrasions on the surface of the glaze. On the right side in Figure 4, another patch of abrasion is seen. Abrasions like these are common when the ware had been in used for a long time; it is from the wear and tear process that goes with continuous use of the ware. They certainly mar the appearances of the ewer a bit, but they also serve to show that the ware had been in use for a long time.

I’ll show you a few more photos showing this abrasive lesions (Figures 5-9). But at the same time, you should take the opportunity to look at the specific features of the Sumali Blue dye in these photos.

Figure 5

Figure 5

You will note that the abrasion of the glaze here is rather extensive. The shape and colorful reflection of the plaques are consistent with the Sumali Blue dye.

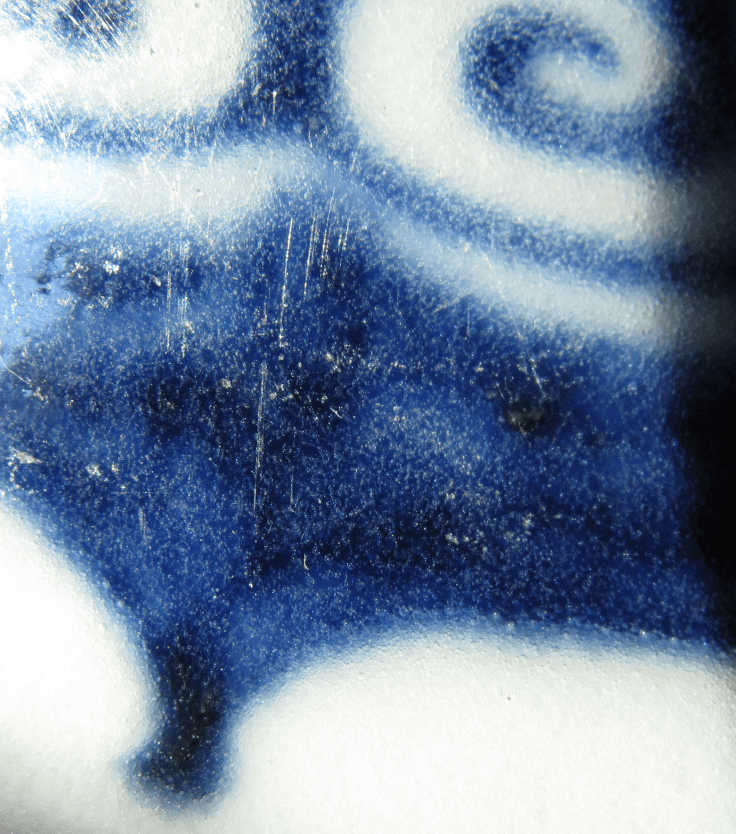

Figure 6

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 7

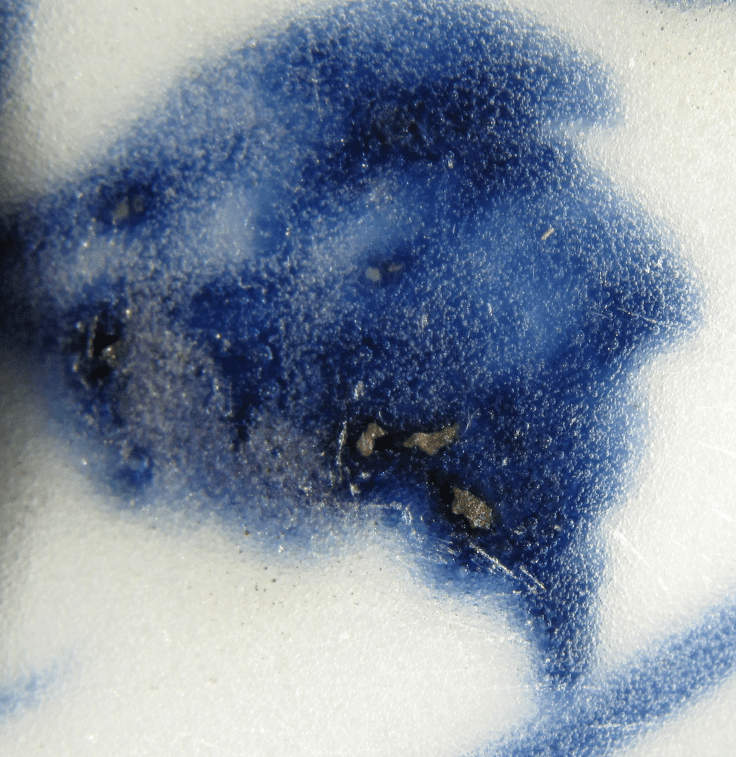

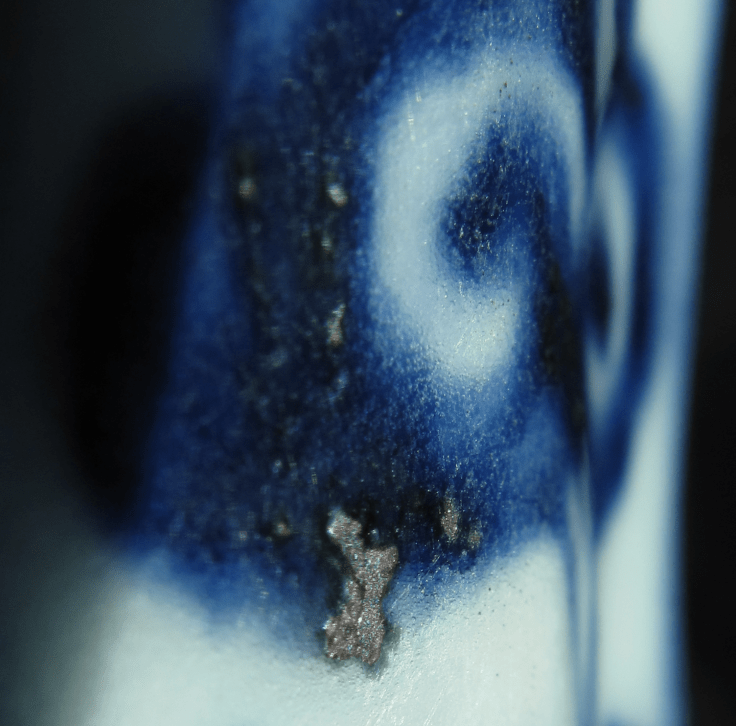

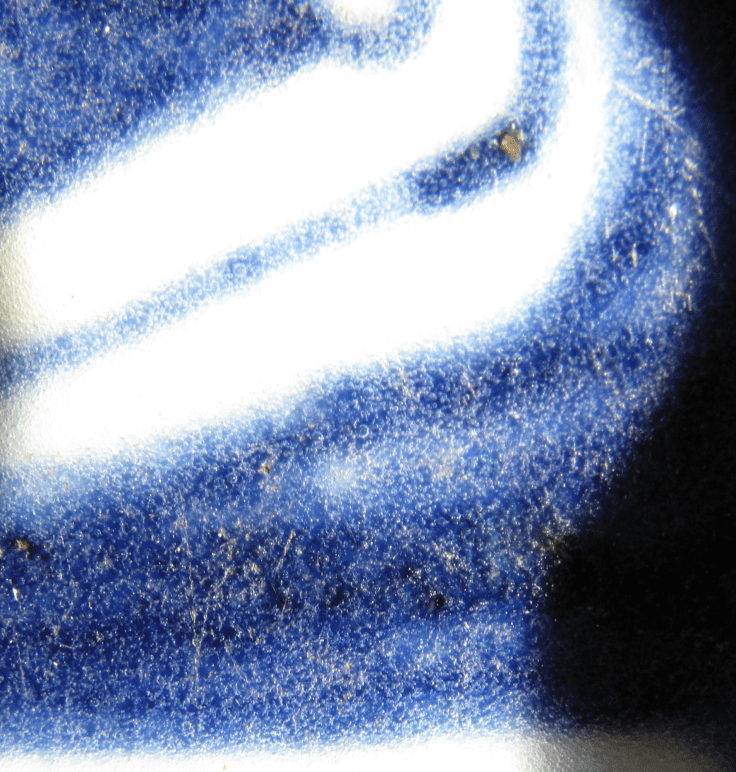

Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the same patch of the abrasive lesion, but the lighting is a bit different. You must pay attention to the differences. In Figure 7, the lighting is such that you can see the different shades of blue very clearly. In some areas, the sapphire blue is well shown. It is a beautiful blue, do you agree? Also note the pearly white large bubble just below the biggest plaque.

I’ll just show you two more photos of these abrasions.

Figure 8

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 9

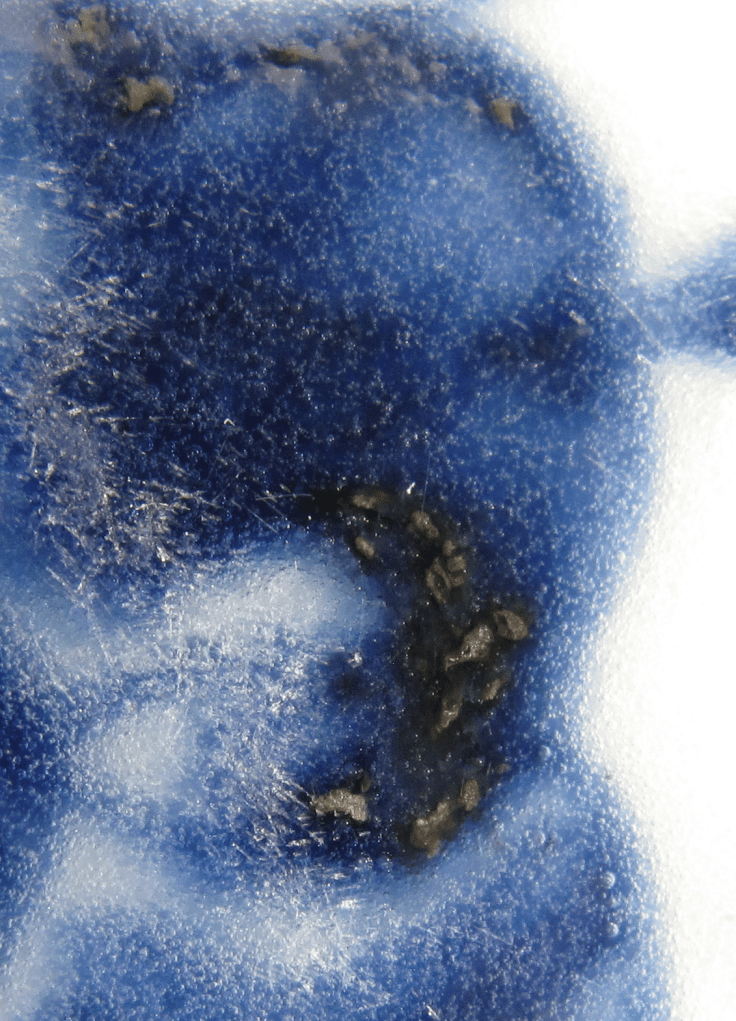

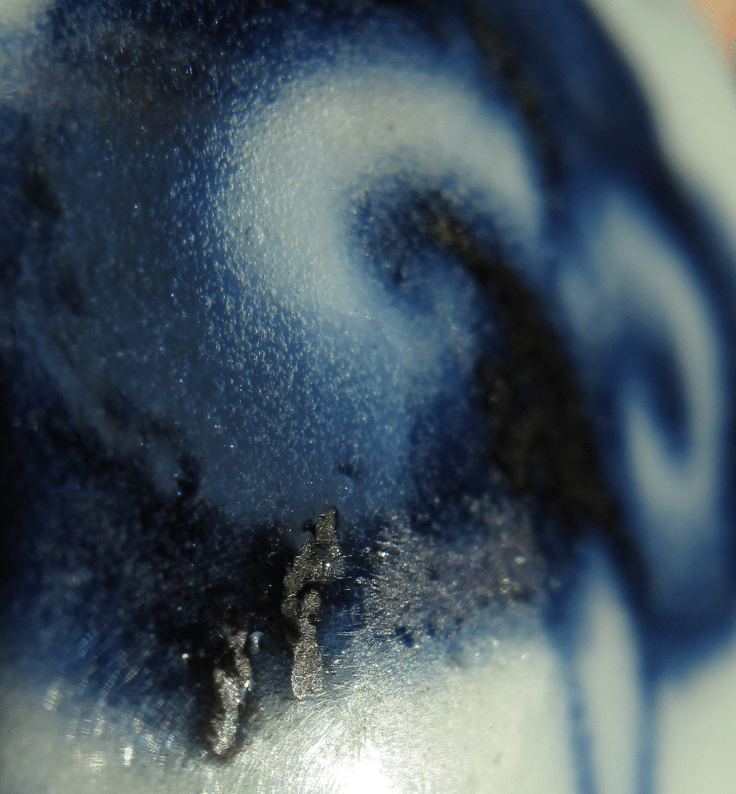

Note the abrasive lesions in these two photos, especially in Figure 9 where the abrasions are rather diffused. Aside from the plaques, you can see the lacunae very well. These lacunae are well defined, but not well packed, as you can see. Again, in Figure 9, you can see the very beautiful blue coloration, suggesting that the blue dye pigment is of very fine quality. Note the behavior of the flare. It is slightly different from those flares that you have seen before, probably the flare is not associated with plaques.

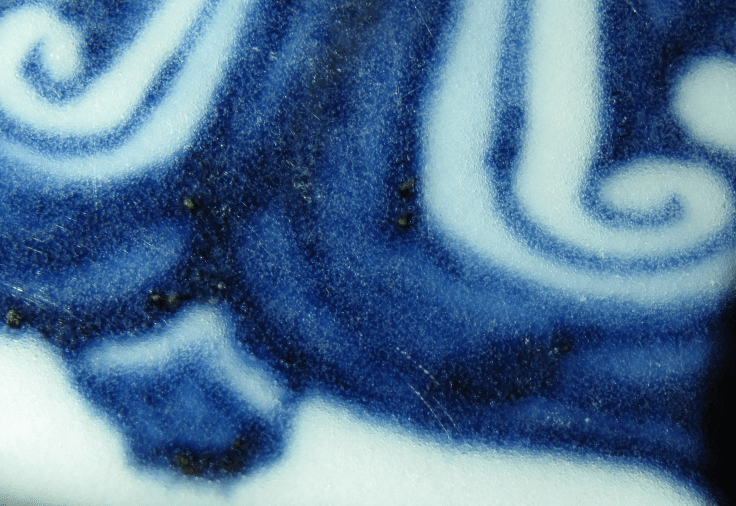

Those flares that are associated with plaques, they are quite the same as those you have seen before, as in Figures 10-13.

Figure 10

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 13

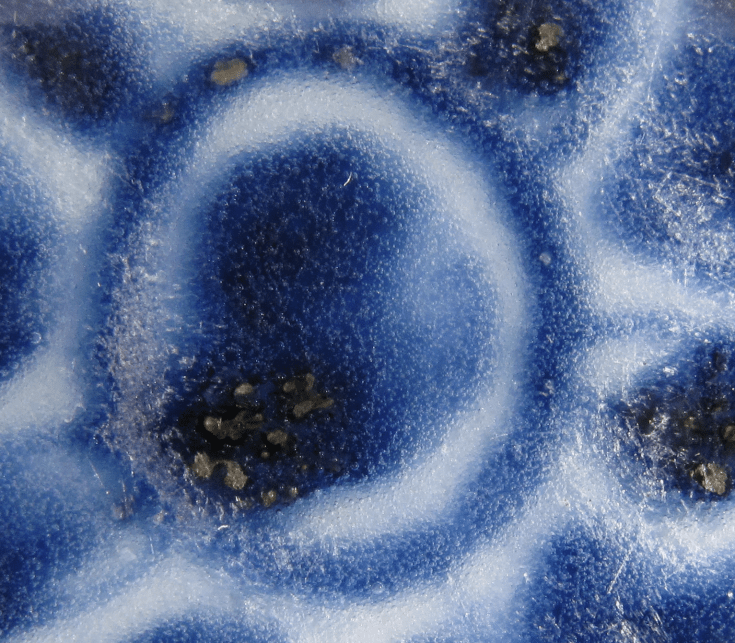

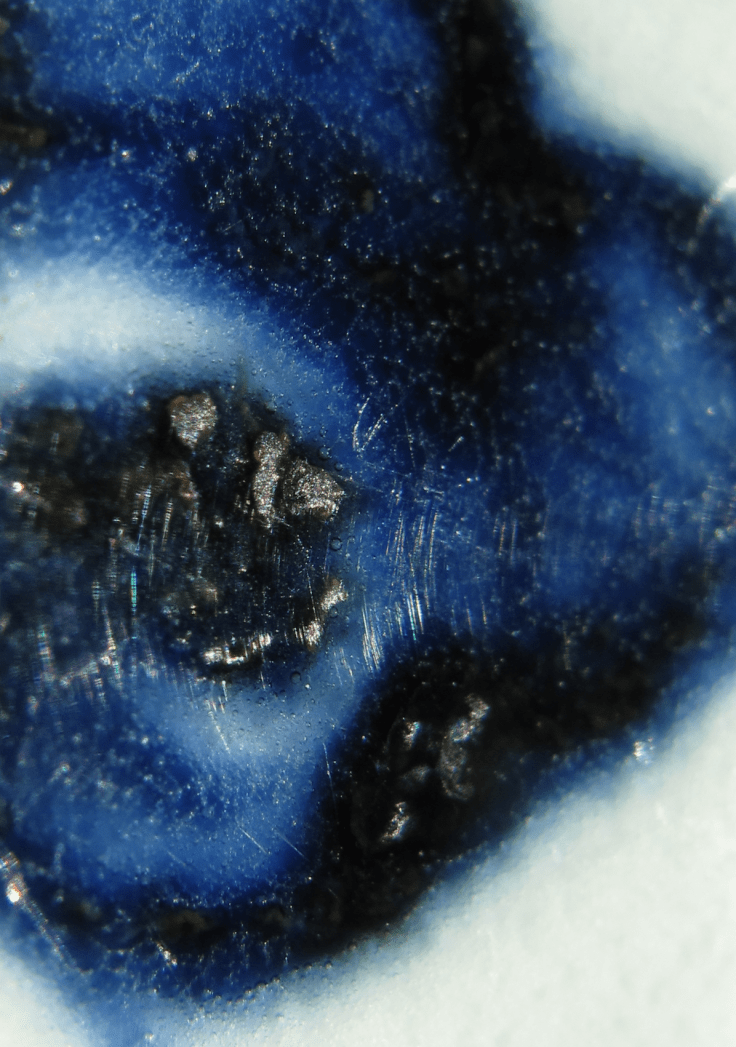

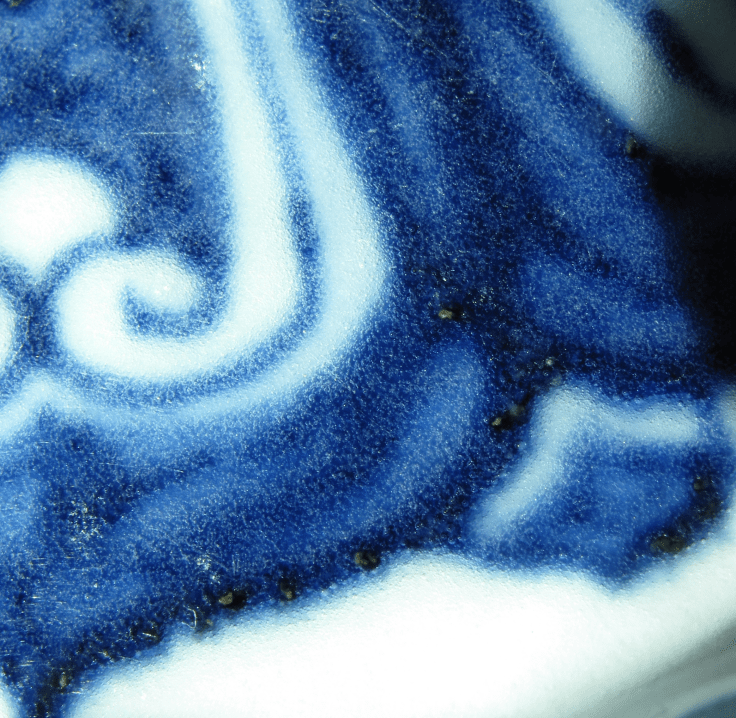

In Figure 13, another feature that is very typical of Sumali Blue dye is shown. If you blow up the photo, you’ll see that in the large dark blue patch, there are many large bubbles hiding there. In this ewer, this features is almost everywhere. I’ll show you a few photos (Figures 14-18).

Figure 14

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 15

Figure 16 IMG_4743.JP

Figure 16 IMG_4743.JP

Figure 17

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 18

In these photos, Figures 14-18, you can see large bubbles lurking in the dark blue. Not only that, there are quite a few instances where there is a string of large pearly white bubbles at the margin of the blue dye. These features are so unique to the Sumali Blue dye that their presence indicates that the ware is without a doubt a Yongle or a Xuande.

Before I end this article, I must show you a few more photos that I think is interesting. I’ll show you three photos of the neck joining the shoulder (Figures 19-21). At where they join, the glaze is particularly thick, and you can see there are many small bubbles gathering there. As is typical of Yongle, these small bubbles give you the impression that they are all trying to rise to the surface and to get out from there. Blow the photo up and see for yourself. Also, the flares and drippings are much more obvious that in the body. It is easily noticeable. Why should there be such differences? I’ll have to say that here, the potter was using two different dye pigment in this ewer. The dye in the neck has the tendency to have more obvious flares and drippings.

Figure 19

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 21

Look at the foot rim, and you’ll understand what I mean (Figure 22). Here the dye used is the same as the body. Any flare and dripping here, unlike those in the neck, are very subtle.

Figure 22

Figure 22

And at the mouth, it is very much the same as in the neck (Figure 23).

Figure 23

Figure 23

I’ll just finish off with another photo (Figure 24).

Figure 24

Figure 24

Here in this photo, if you enlarge it, you can see the small bubbles in different colors. Quite a beautiful sight, but you need to take the photo in a certain angle to show this reflection. But if you are to look at the ware in your hands using a magnifying glass and under the sun, this colorful scene can easily be seen. It only show that in evaluating a ceramic ware, one important thing to do is to examine the ware with a magnifying glass under the sun. It is much more certain than looking at a photo. You will not make any mistakes.

With all these special features of the Sumali Blue dye established, do you have any doubt that this ewer is not a Yongle, even though it is so rare? Do you need any provenances? I myself believe these features are stronger proof than any provenances.