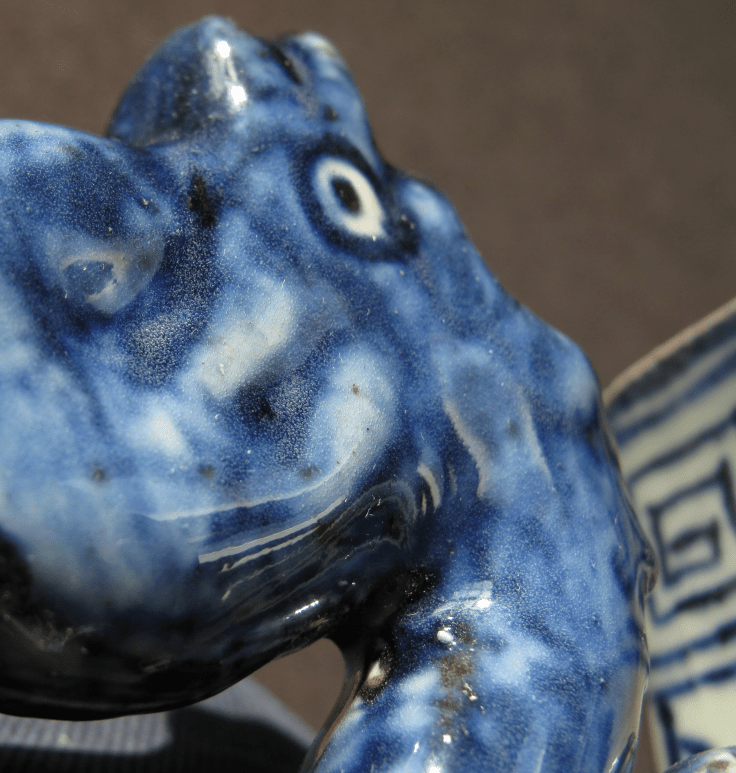

During the eighty years, from the late Yuan Dynasty to the end of Xuande, when The Sumali Blue dye pigment is imported, ceramics in China have undergone a series of changes. It is easy to understand they evolve all the time, if we were to compare them to the technology that we have today. The shape of the ware, the size, the design and the material used change from time to time. Even the nature of the Sumali Blue dye, and the way it is applied in the motif differ from one period to the other. We have observed these changes in our study of the wares in those periods.

A good example would be the size of the ware. Yuan Blue and Whites are known to be large. They are larger than those in the Yongle and Xuande period, not to say the Chenghua era. The blue coloration in Yuan Blue and Whites is, generally speaking, of a deeper blue. The potters apply the dye so very liberally that sometimes the blue color is very dark, so dark that it might look like blackish. The Sumali Blue dye is well-known to be very expensive, and we are sometimes puzzled why potters use the dye so very freely. My speculation is that when the sellers first export the dye, they never realize the demand for the dye would increase in an exponential manner. They market it with a great promotion. The first potters using the dye do not find the cost to be prohibitive, and they use the dye lavishly.

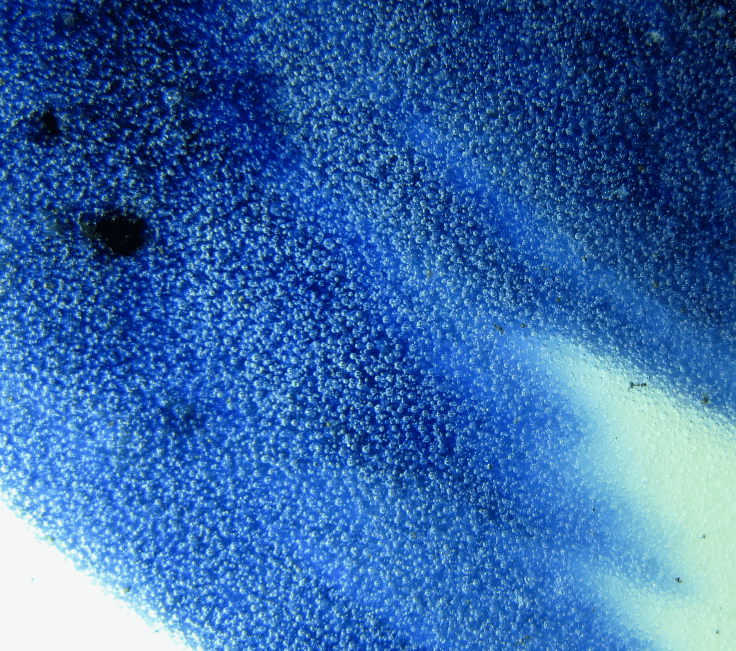

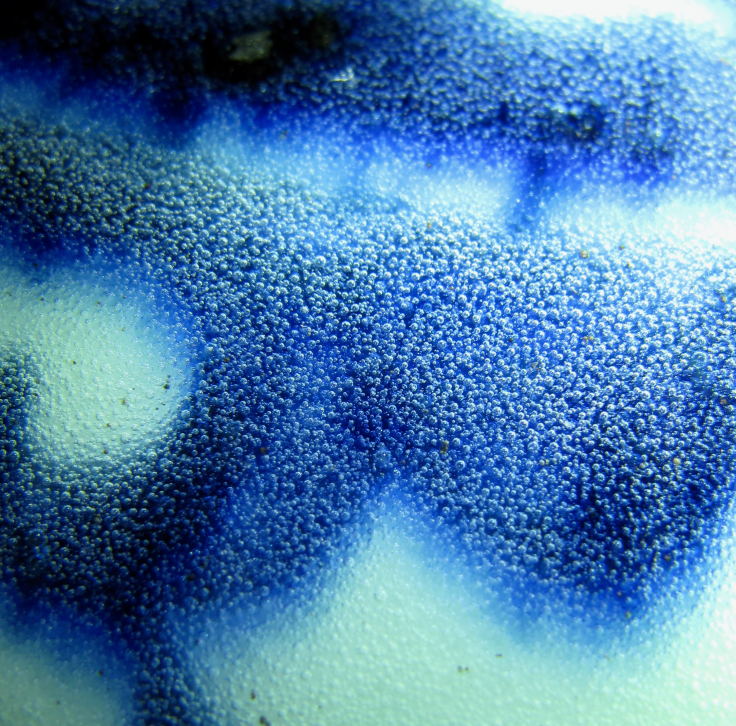

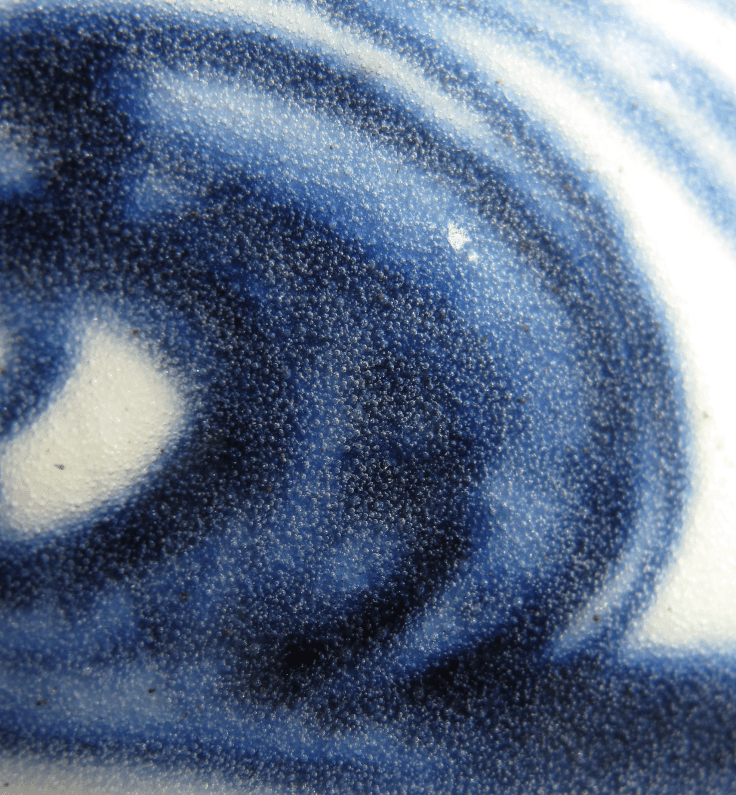

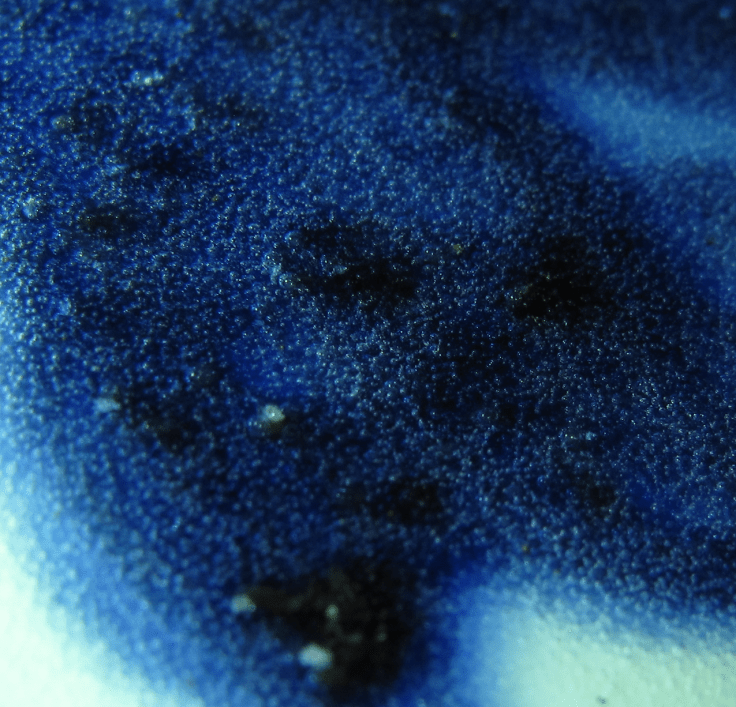

When the sellers find out that the product is in good demand, they naturally increase the price sharply. The potters in Yongle and Xuande have already found the dye expensive, and they want to cut the cost of production by using less dye—diluting it and applying it in a controlled manner. The blue color in those two periods are noticeably less dark in color. From an aesthetically point of view, it is difficult to say what is a better color—the very dark blue and the lighter blue. But there is one effect that we can observe in the bubbles. The bubbles in the Yuan B & Ws are much more tightly packed, no doubt due to the deeper color. I’ll show you this in this Yuan Zhihu, or ewer.

Figure 1

Figure 1

As I have told you, Yuan wares are generally large. This Zhihu is large. It measures 19 1/2 inches in height. The motif is clearly Yuan, and the way the motif is drawn is also Yuan. But that has nothing to do with the authenticity of the ware. The evaluate it, and to say for sure that the ware is a Yuan, the only way is to look at the characteristics of the dye, and see if the characteristics are consistent with the Sumali Blue dye. We will now do that.

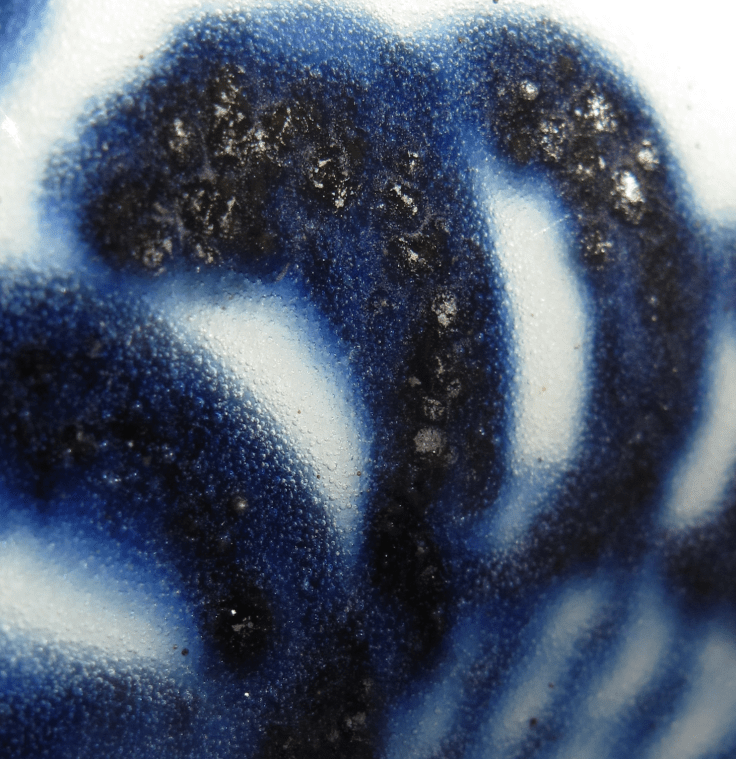

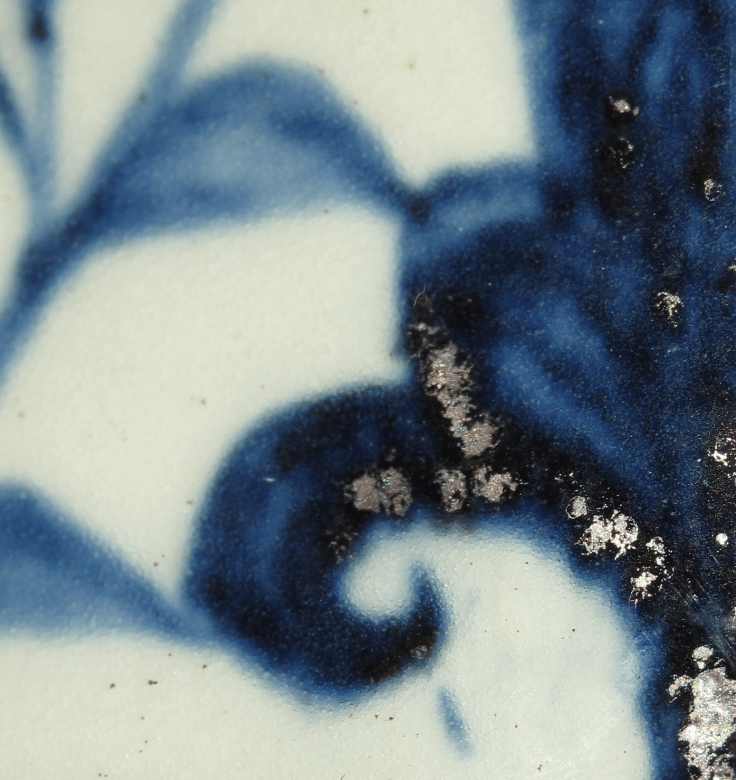

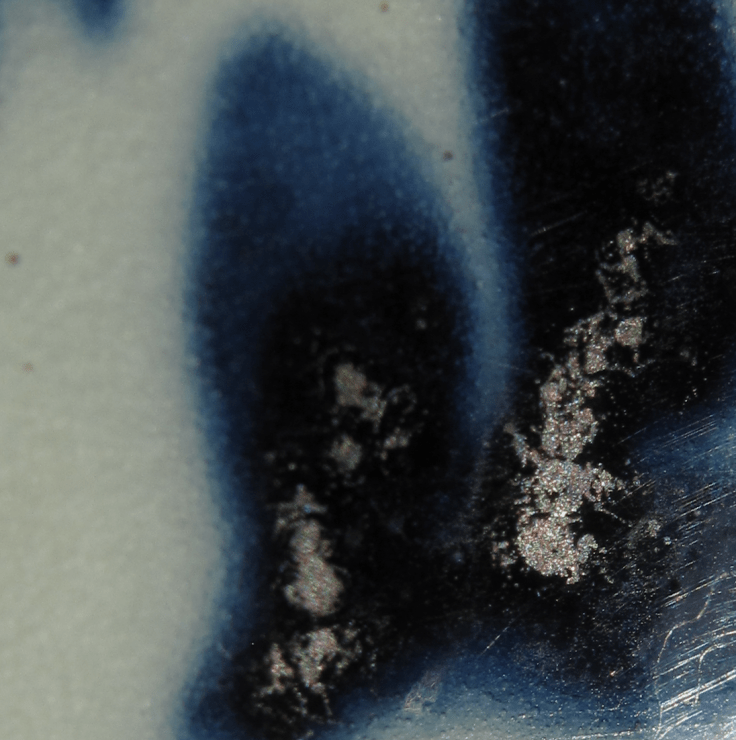

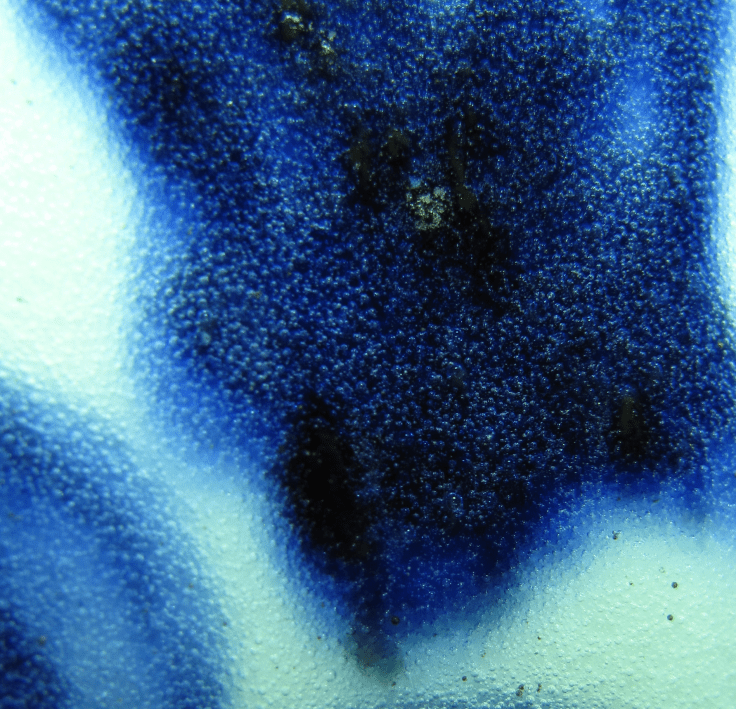

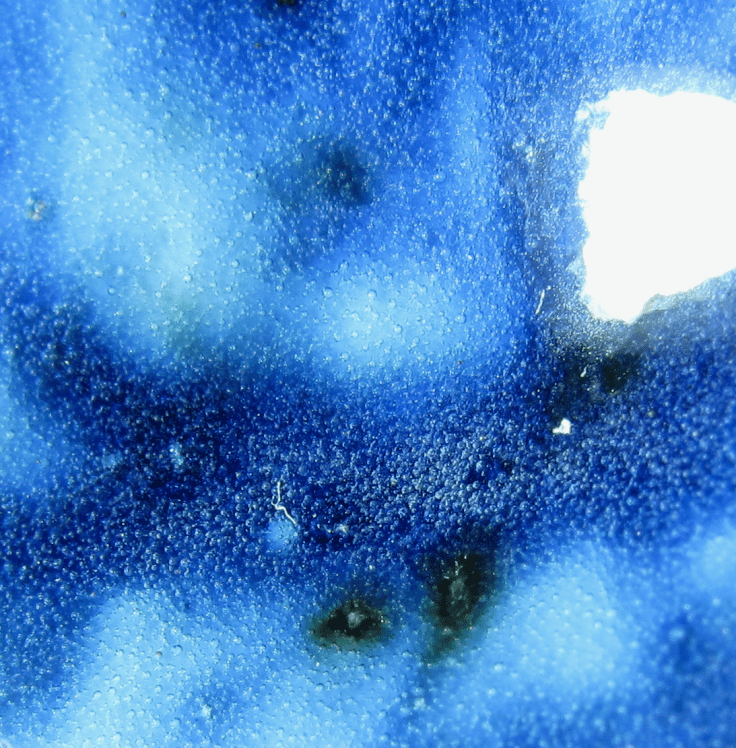

Before going into the bubbles, let us first see another prominent feature of the Sumali Blue dye, the plaques. By now, you must know that plaques of B & Ws in Yuan period are, most of the time, mature plaques. That is to say, a plaque with a metallic foil floating on top of a muddy layer at the bottom. We have seen that the muddy layer in some Yongle and Xuande wares are extremely colorful when seen under the sun. This, I suppose, is due to the very complicated structure of the muddy layer, with a lot of very reflective compounds in it. The metallic foil is mainly aluminum and its compounds, so that the structure is relatively simple, and the reflection under the sun is not as colorful (Figures 2-8). Not only that, the presence of the metallic foil somehow makes the muddy layer reflect no color. Its presence is only represented by some blackish shadows around the metallic layer in a photo.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 8

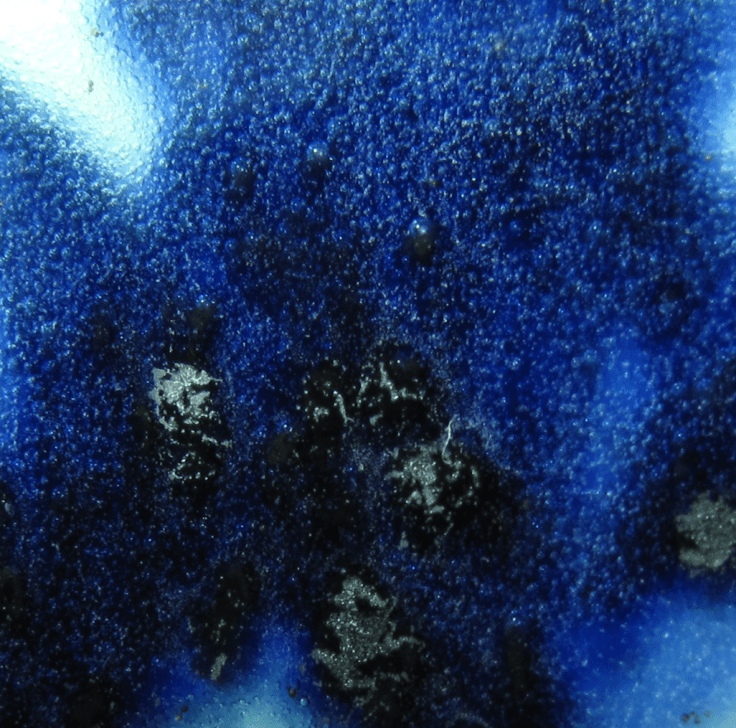

Note the shape of the plaques. They are typical of those of the Sumali Blue dye, and they all lie within a pool of very dark blue color. In many of these photos, small flakes of plaque breaking away from the main one are also seen. These small flakes of plaques probably have a different density, and are denser and heavier than the main plaque, thus falling faster under gravity than the rest. This is particularly noticeable in Figure 8. When such flakes of small plaques are present, it generally means that the dye pigment is of good quality. In the same figure 8, which is taken under LED light, the bubbles are seen more clearly, because of the brighter light. You can see the bubbles are tightly packed. I’ll show you more of these bubbles in the following photos.

Figure 9

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 14

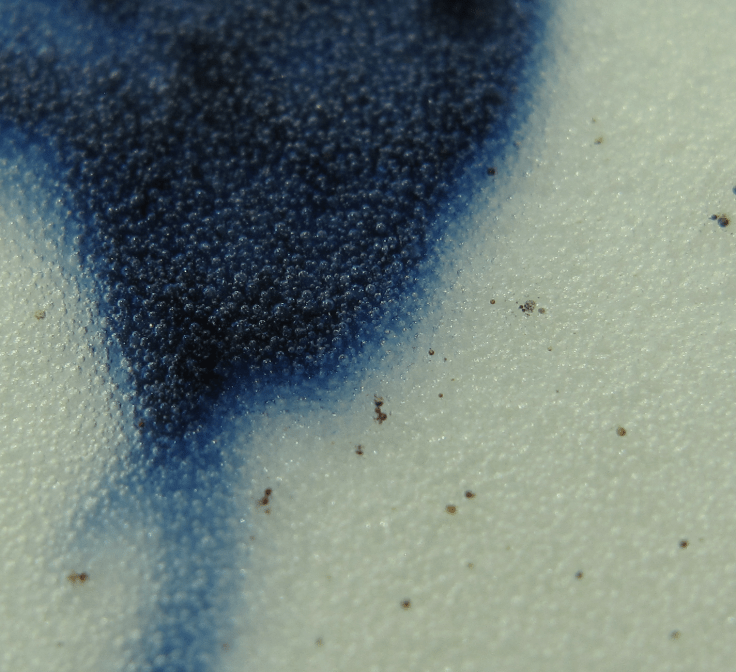

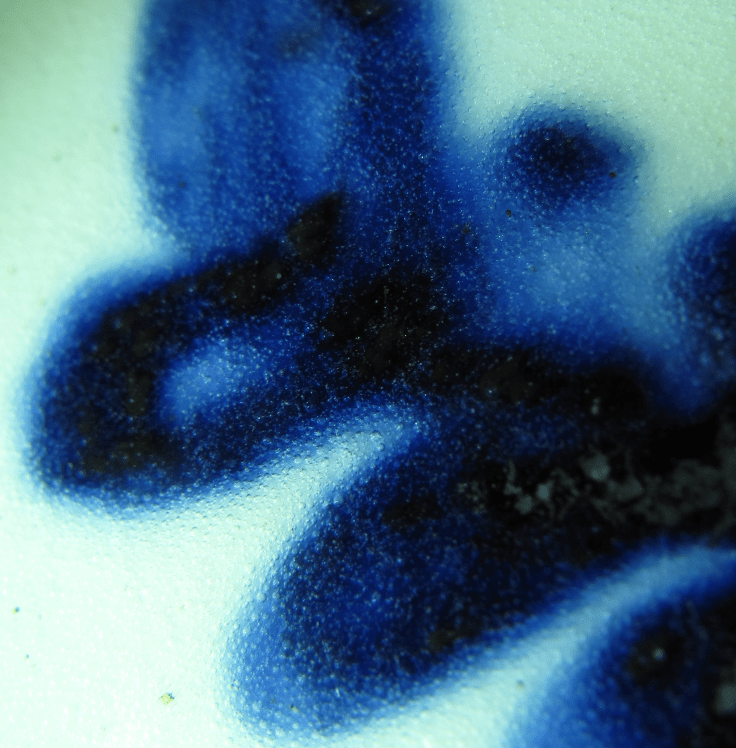

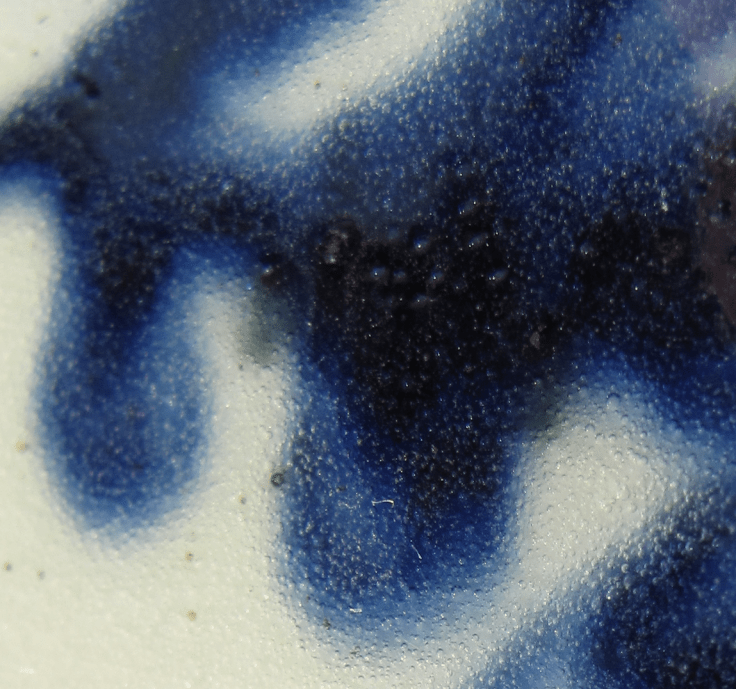

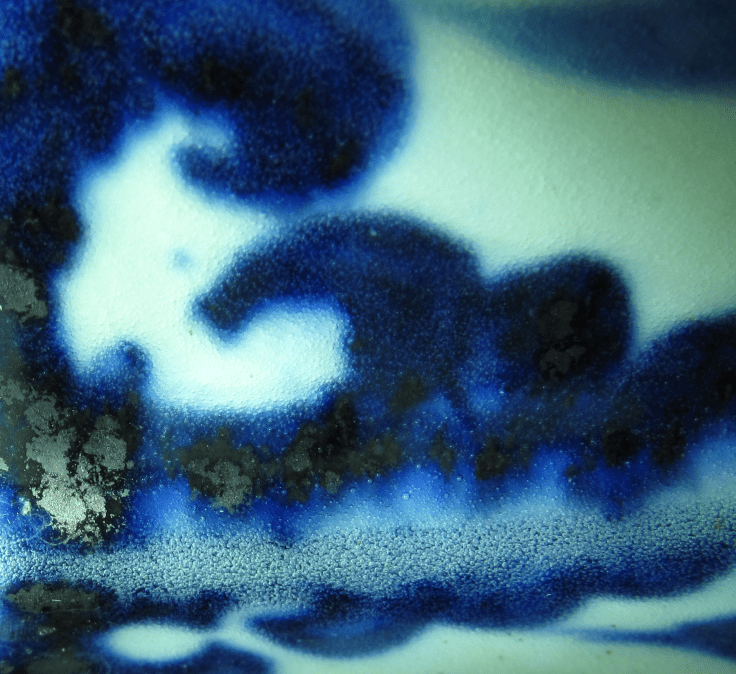

Look at these six photos (Figures 9-14). Are not the bubbles tightly packed? But the interesting thing about the bubbles is that they do not seem to be disorganized. You do not have an impression that everything is in disarray. You also need to look at the drippings—the lower edge seems to be flaring out. And look at figure 13 and 14 again. Can you find quite a number of large bubbles hiding in the blackish area? This is typical of Sumali Blue dye—large bubbles lurking in plaques and plaques that are not yet fully formed, which only show up as blackish patches. I’ll show you a few more photos presenting in this manner (Figures 15-18).

Figure 15

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 18

Look at these large bubbles, all hiding in a pool of blackish patch. In figure 18, the large bubbles are almost like a nest of eggs. This kind of bubbles is only seen in Sumali Blue dye. No other dye in Chinese ceramics will give you this kind of picture. When you see them, the dye has to be Sumali Blue dye, and the B & W is genuine and real.

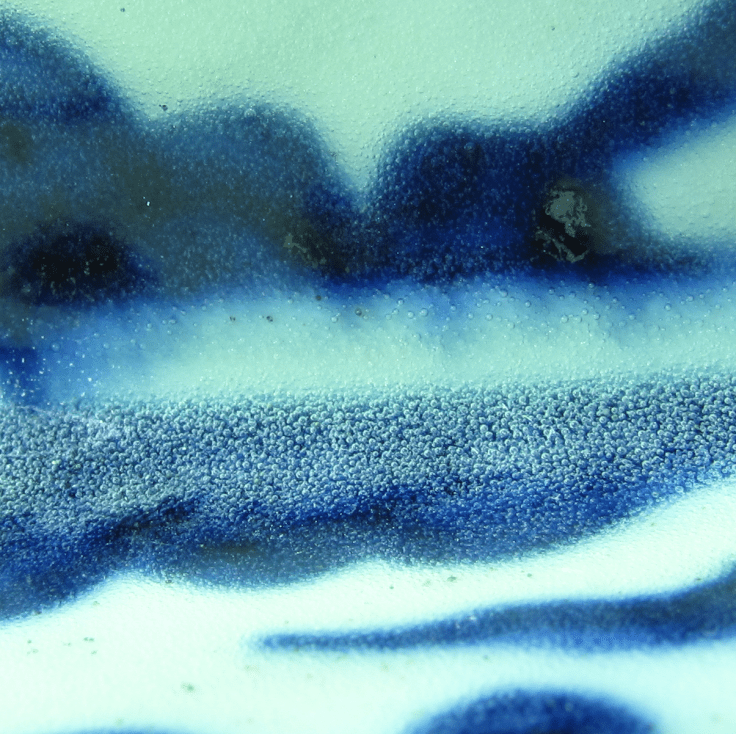

In other areas where the dye is not so liberally applied, the bubbles are different.

Figure 19

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 21

Figure 19 is from the mouth of the Zhihu, and Figures 20-21 are taken from the bridge connecting the spout to the body of the ewer. In figure 21, at where the bridge has a depression, the bubbles would all go there, resulting in a high concentration of bubbles. In the lighter blue areas, you can see bubbles linking up as though by a piece of short string, another familiar phenomenon seen in the Sumali Blue dye.

At where the two main pieces of the body joined together, the bubbles are also highly concentrated (Figures 22-23).

Figure 22

Figure 22

Figure 23

Figure 23

With all these features matching very well with the features of the Sumali Blue dye, there is no reason to doubt that this Zhihu is not a a genuine Yuan B & W. Not only is this genuine and real Yuan, but this is a piece that belongs to the very early period when the Sumali Blue dye is first imported to China. The reason? I’ll show you two photos as my argument.

Figure 24

Figure 24

Figure 25

Figure 25

Figure 24 is the bottom of the Zhihu, and Figure 25 shows the mouth of the ewer and the mouth of the spout. You will note that both the bottom and the mouth of the ewer are unglazed, whereas the mouth of the spout is glazed. It only shows that in the beginning of making the first B & Ws, the potters are quite unsure of what needs to be done, and what does not.

Leave a comment